In the book world, tchotchkes abound. Every couple of weeks promotional stuff arrives: lapel pins, fancy bookmarks, canvas bags, kids' games and little puzzles, etc. Can be a bit hard to keep track of it all. Some of it clearly made more sense in a marketing meeting than it does in a bookstore. Who wouldn't want an enameled pin of a crashing plane? No explanation. I guess you have to read the book. For reasons that remain unclear, we recently got quite a haul from a Buddhist press. Among the usual bookmarks and bags, there was, inexplicably a beautiful little embossed wooden thumb-drive in a wooden box. Downloading enlightenment? No idea. There's a lot of that. People do love a give-away, but this stuff goes stale like butter-based pastry. Booksellers are notorious for not wanting to throw away yesterday's promo. We like shiny stuff as much as the next magpie. Junk drawers in desks across the independent bookselling business are full of crunchy rubber-bands, old staff recommendations, dead pens, and promotional pins for books we have long since forgotten, most justly so.

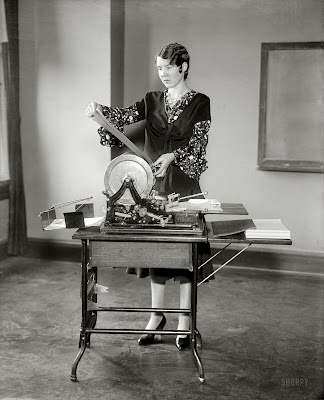

Twenty years ago there was something of a renaissance in book-related "side-lines." (This is what booksellers call anything sold because of books -- but not a book.) Some of this is eternal, like Seussian stuffed animals and refrigerator magnets with quotes from Dorothy Parker. For a hot-minute there we also had finger-puppets of famous authors in felt, famous authors' mugs on mugs, multiple lines of famous authors on greeting cards, famous authors action figures, inexpensive book jewelry, famous author candles, book bumper-stickers, famous author Christmas ornaments. Couldn't swing a cat-book without hitting a Virginia Woolf stuffy or a Charles Dickens puppet. And then, as was ever the way of such things, all of that rather ran its course.

I was given various of the items mentioned above. Find I didn't keep much, or if I did I've no idea where they might be now. I was never much for the side-lines. Which isn't to say that I am not susceptible to collecting the book-adjacent, if only in a small way.

Of my favorite Dickens collectibles I have just the two Royal Doulton figurines, for example. The Artful Dodger was a gift. Tony Weller I found in a junk shop. There was a moment when -- child of the seventies as I am -- I really aspired to "collect 'em all!" but that never happened. Too expensive, honestly. Saw Pickwick and The Fat Boy in a real antique shop when we first moved to Seattle. Well out of my price range. I also remember bidding for a complete set on eBay, more than once, back when I did that sort of thing. Never won the auction, and just as well probably. Each figurine stands no more than four inches high, but all together there were twenty-four Dickens characters depicted in the Royal Doulton series and that's rather a lot for a crowded personal library. (I don't even have room for all my books about Dickens, let alone collectible glassware.)

The potters Doulton & Co. started business in 1815 with the usual assortment of jugs, jars, mugs, and drain-pipes. (Dickens would have approved. He was a great champion of modern drainage.) The author was himself introduced to the world just three years earlier. He left it the most famous novelist in the world in 1857, well before the ceramics firm received their "Royal Warrant" in 1901 as a vendor to The Crown. Can't find any information about the designers of the figures, when they went into production, or how they selected the characters -- some seem less obvious than others. Only thing I do know is that the Dickens figurines were discontinued in 1983 or 1984 and prices went up accordingly.

They are uniformly charming and beautifully made. Most are immediately recognizable to any reader of Dickens. A few, like Oliver Twist and David Copperfield may seem a bit generic. Other obvious candidates for reproduction in small, like Betsey Trotwood and Mr. Dick seem not to have made the cut.

Full disclosure, I do have in my library three framed Dickens illustrations by Joseph Clayton Clarke, better known by his pseudonym "Kyd." He made a good living producing mostly cigarette cards and watercolor illustrations, many of Dickens characters, specifically to sell to collectors. I have prints of Mr. Bumble, Sairey Gamp, and Trotty Veck from The Chimes. I also have salt and pepper shakers of the McCawber and Sairey -- a distinctly odd couple, may I say. I have a small ceramic flask depicting a seated figure of Fagin with a cork in his hat, and I have a genuine curiosity in a small ceramic figure of Dickens giving a public reading at his famous lectern, though it is actually a portrait of the great Emlyn Williams as Dickens in the actor's storied one-man-show, making it all the more interesting and obscure.

Important to remember that Dickens was very much of his time, and as a Victorian, and something of a dandy, he liked fine things and what we might see now as an excess of bold checks, rich color, lace, fine china, watch-fobs, rings, furniture, and decoration. Kept a charming white porcelain monkey-- still extant -- on his writing desk, for example. He was always fond of collecting things, people, pets. He loved crowds and crowded interiors. (The most alien aspect of Victorian taste may well be their mania for filling every available surface with pattern and detail and things upon things; Turkey carpets and on them more furniture than would fit and antimacassars on it all, cabbage-roses on the wallpaper and pictures to the ceiling and domed wax flowers and china cupboards and brass fittings and stuffed dogs and stuff, stuff, stuff, stuffed everywhere. Maybe it kept the rooms warmer? It was as if the highest aspiration of the rising middle class was to live inside one of Mary Todd Lincoln's over-decorated dresses.)

Dickens was also the English speaking world's first real celebrity, at least the first person famous for accomplishing something that didn't require conquest, theft, inherited title, or physical deformity. (You will find a convincing argument for this in Jane Smiley's short biography of Dickens published in 2002 as part of the lamentably ended series of Penguin Brief Lives.) As such his image, his characters, and his books were reproduced in all sorts of unlikely offerings ranging from pirated editions and unapproved dramatic adaptations -- some of which premiered before he'd finished writing or publishing the novels from which the stories were taken -- to unauthorized advertisements on sidings and packaging for wares as various as tea-tins, cigar boxes, pill bottles, pins, hats, toys, and all manner of whatnot. Copyright being a battle yet to be really won, and modern branding and licensing still yet to be dreamt of, Dickens made nothing from most of this. (He did occasionally try to approve and or improve some of the stage-adaptations, but it was a losing battle.) From nearly the moment the Pickwick Club first took to the road, images of that venerable gentleman began to appear stuck to soaps and cigars, advertisements and handbills. So it would be throughout the writer's life and long after. More than anyone before him, including Sir Walter Scott, Dickens' characters became part of the visual landscape of his time. Some, like Scrooge and Pecksniff, would settle in the dictionary as well. Shakespeare just here is the only real point of comparison. Other writers of Dickens day may now have a house museum and a statue, may even have a grave in the Abbey, and while they may have created a ubiquitous character like Lochinvar or Jane Eyre, none saw their invention everywhere quite like Dickens. (The best point of comparison would probably be later examples in popular film culture like Mickey Mouse or Charlie Chaplin's little tramp.)

Charles Dickens was unafraid of popularity, to say the least. Not for him the aristocratic reserve of Sir Walter Scott that kept his name off the Waverley Novels until near the end of his run and his money. It was all very well for a gentleman to be a poet and collector of quaint Scottish Ballads, but a vulgar writer of popular Romances? (Meant in the poetic sense -- his being historical fiction, not the modern pop genre of courting stories.) Dickens rose in the world by his pen, and only his pen. To be noticed, and published, and paid, to be recognized on the street and addressed by his nom de plume "Boz," meant Dickens could be somebody. To be somebody was not a guarantee. Lots of somebodies either lost everything and reverted to being nobodies, or they simply ceased to matter. Dickens knew the bitter experience of his father's failure to keep his family out of the Marshalsea Prison for debt. Dickens knew poverty and all the rest of his life he kept the smell of it somewhere about him, and the secret of his family's shame. He fought to dispel the corrosive myth of gentility, and the brutal conditions of the urban poor. He knew. He remembered, and reminded himself nearly every day as he walked the length and breadth of London, often at night, looking in at every dark doorway, up every alley, listening and watching and walking as if into the dark to tame it and make himself it's master and avenger. Fame meant money, and the public's affection, and the kind of respect that meant more than respectability. What he wanted and what he got was power.

George Orwell famously said, "Dickens seems to have succeeded in attacking everybody and antagonizing nobody." Even a glancing review of English satire, from Chaucer and Shakespeare to Dryden, Pope and Swift, even to Dickens' immediate predecessors like Leigh Hunt and Hazlitt, will show a predictably savage response from the satirized. Power resists puncture. Insults to assumed or inherited dignity, perceived or intended, can have grave consequences, particularly in a country whose Constitution was not so much written as gradually accumulated over time, more philology than philosophy. Enemies have always been easily made on the page and few writers in the history of the language filled more pages than Dickens. His output was prodigious, even by the extraordinary standard of his day, his published books containing thousands upon thousands of words. He wrote hundreds of letters, gave hundreds of speeches and public remarks. His recognized journalism, only recently collected, runs to many mighty volumes of nearly equal, perhaps even greater weight than all his published books. (I have bravely restrained myself from trying to buy these new volumes of Dickens' nonfiction.) He wrote to eat, to live, and he wrote constantly. In nearly everything he wrote he sought not only to entertain and enlighten but to damn, blast, and shame the devil. How could he not make enemies?

The answer is he did. Of course he did, and not a few well after he'd died. But Dickens -- better than any writer before him, again save Shakespeare -- had the trick of making no man a hero, including himself. Dickens is always on the reader's side, he is with us and we are, most of us, an unheroic lot. Virtue may triumph, as I'm sure Dickens believed it should and eventually might, but usually this happens only in small acts of bravery, often performed by unlikely, much compromised, put down or put upon people. Rarely is a protagonist, however good, saved in Dickens but by others. Dickens believed in us all, individually, believed that we might yet prove to be better than we might be. And he spared no one. He begins his most autobiographical novel with a question. "Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show." David Copperfield's answer, and Dickens' own answer is a resounding no. There are no heroes. There is help. Even the snobs and the critics, the rivals who might have resented him, even his avowed enemies were more often than not disarmed by this instinctive appeal to our collective better nature, even as he mocked the lot of us for our cowardice, snobbery, greed, and stupidity. His humor was as universal as his faith was deep if unorthodox and individual. God helps or he doesn't much. We may help ourselves, but we need other people. Hard not to blush. Perhaps it's too simple, but it is true. It is also hard to deny. It strikes me as a very English problem, hating Dickens. Must have been deuced difficult, going against the man who made Queen Victoria laugh aloud. What has he ultimately called for but kindness? Argue against that and you will look a git. Also? It's one thing to claim slander, but quite another to admit to being the butt of a joke that set a whole nation laughing. Fight that. Find a jury that won't grin.

The fact is they'd never seen his like before. The most popular writers in the whole history of English had never had so big an audience. If everyone could be said to know him by the time he was thirty, it was because nearly everyone could afford to read him, and did, or had him read to them because of the revolution in serial publication and cheap editions. The industrial revolution was as much the triumph of print as of the piston and steam. More though. He didn't speak for the English, but to them. He still speaks to us.

Our author was also very careful of institutional targets. It is a truism as old at least as Rome that nobody loves a lawyer. In Bleak House he savages the Court of Chancery, but not the Law. As early as Serjeant Buzfuz and Pickwick's time in the dock for breach of promise, Dickens damns lawyers, but not the Law. Mrs. Jellyby is ridiculous, but Charity is not. Nickleby's theatricals are ridiculous, but Theatre is a noble thing. Bankers are invariably low-minded men, but The Bank of England is let stand. Capitalists are heartless, but Business is good. the Circumlocution Office is a den of boobies, but Her Majesty's Government, for all its sins, is not without its uses. Clergymen may be less than good Christians, but Christianity is God's gift. The list goes on.

This respect for larger social abstracts, Dickens' sometimes too simple faith in his own England, and his own God, lent themselves to serious criticism even in Dickens' day. He was no radical in his politics and feared revolutions as much as the next self-made man with a mortgage on far too large a house. Later still when academia and the critics took to wearing new Party livery, Dickens, still popular in the Russian Soviets to the end of the last century, came in for a serious drubbing himself, and not without cause. He could never quite accept the idea of collective action. People should help one another, but not The People. That abstraction was dangerously ill-defined. Didn't trust it. Later still he was quite rightly taken to task for unthinking antisemitism, xenophobia, and racism typical of his time. And yet, unlike nearly all his contemporaries, and all of his critics, and some who were probably better people if not such great writers, Dickens survives.

If everybody then read him and knew him, and so many loved him, it was also because he wrote nearly everybody into his books. If you can read Dickens and not meet therein your aunts, your neighbors, your clergyman, your boss, your elected representative, your dog, and your dad, if you can read through Dickens and never see yourself, I fear you may have missed not just the point but your own portrait (the gallery, it must be said, is crowded.) We are meant to recognize ourselves in even our enemies. There but. And he meant it. And nearly all his victims knew. The gentlemen of the Circumlocution Office knew who they were. They might very well resent the man's impudence and did, but what could they do? Does one admit to being a Barnacle? Even so dim a light as a Sparkler probably had the sense not to call himself so without smiling.

In Dickens, particularly in the later novels, the sign of a genuine villain is not that he is unaware, or even unconfessed, but incapable of change. Miss Wade may be justified in at least some of her suspicions, but Miss Wade is immoveable, poor soul. Mr. Merdle leaves only ruin after him. No way to change. It's too late. It should be enough to know that Henry Gowan beats his dog, and it is. No coming back from that. Mrs. Clenham has faith, but very little charity. Let her sit with that, ultimately silent as the tomb. Flintwich remains as twisted as his neck and cravat. Riguard? A house could fall on him and he'd still be a devil to the end. But only the very worst people reject their salvation. In Dickens' theology redemption requires acts, and often as not small ones at that. God can even forgive, at least a little, so vocal a Christian as poor Arthur's mother, if she will just do a selfless thing. (Dickens need not forgive her, but Jesus might.) The novelist is free to punish or to pass over. Some escape. Most do not. The God of Charles Dickens is relentless mostly in his mercy, but not indefatigable.

As the French landlady in Little Dorrit says, not knowing that among those she's addressing sits a murderer, "... there are people (men and women both, unfortunately) who have no good in them -- none."

Dickens reserves his deepest sympathy, always, for the broken. The most virtuous people may suffer, but their virtue is to some extent it's own reward. God may yet see to them (or at least the novelist probably will in the last chapter, if they survive.) But spirits can be crushed, minds wander, hearts may be broken beyond repair. One's circumstances may be cornered so tightly as to allow little room for righteousness. And yet, small rebellions may change the world. Poverty precludes all but the slightest charity, but generosity counts all the more for empty pockets. A clerk may do a kindness as well as a great lady, and it's likelier. Silly women may be good. Men may be mad, may mumble and maunder and still make sane men better by the truth. Nowhere is the faith of Charles Dickens, his own simple and thus peculiar Christianity, more evident than when he speaks, in the phrase from the Gospel of Matthew, for "the least of these." As close as the author comes to collective responsibility, the hopeless and the helpless must be cared for. Up to us. Close as he gets to grace may be in innocence.

Didactic as some of this now strikes the eye of the modern reader, I would argue that not only is this always intended to good purpose, but also leavened by Dickens' delight in his language. He may thunder, he may lament, he may weep too loudly for any brightly lit, tastefully appointed classroom we are likely now to be in, but he does not bore and there is beauty even in his excess. We may not like it any better now than cabbage roses on our wallpaper or fussy embroidery, but that is a matter of taste. His was not invariably good. Doesn't mean there wasn't craft in the making of it, or art of its kind in the way it was made. His pity, like his humor is prodigious, almost inhuman and he has the vocabulary for both. We may simply have lost habit of such conspicuous, such noises joy and voluble grief. Not so the Victorians. The Victorians, whatever you may think you know about them, wept easily and often. For God's sake, the man made Gladstone weep over the fate of fictional children, and of sterner stuff few Britishers were ever made. Carlyle too! The most emotionally scotched of Scotsmen.

Important to keep a point of geography in mind too. The whole tradition of the English comic novel -- itself nearly as great a contribution to the world's treasure as English poetry, and more easily translated -- had before Dickens and continuing well after him always tended to satire. Whatever it's pretentions to empire and the devastating harm done by that enterprise throughout the wider world, England is no more than an Island, and a not a specially big one at that. The English have no national epic, no written language to really call their own until Chaucer. (Personal prejudice, but this has always seemed to me a good thing. Better to find one's voice when there's something original to be said.) The language has never been beholden, never entirely settled and the better for it. So too, from the get, English fiction, and the novel in particular. By the time novels became really popular, far and away the most successful English novels tended to be as funny as the language. (What other language in history has gathered up so many delightful if unnecessary words? What other language best expresses itself in such dizzying variety and avoidance of direct address? What other language makes modernist revolutions as different as Hemingway and Joyce?) Yes, there were always the usual romances and heroics, fainting ladies and sturdy young juveniles, etc., but a language overabundant in curiosities and crotchets is better at being funny for being funny. Mutts are funnier, and dearer usually. Doesn't mean they mayn't bite of course. And when Dickens is plain, has anyone ever been so angry, so moving? More devastatingly direct? Only Hardy could make a declarative statement hurt as hard as Dickens.

Being every bit as pious as any of its more Catholic neighbors, The Church of England somehow managed to embrace the Reformation without abandoning any of the pomposity of its elder sister. (The point of the English Reformation was twofold, to obtain a divorce, and to make the liturgy just as dull in English as it could ever have been in Latin.) I suspect Dickens adamancy that he be buried in a simple plot by his beloved little sister-in-law (that perfect, pure, long dead child) had as much to do with his disinclination to Church, cathedrals, Bishops, and funereal pomp as it had to do with his devotion to that forever young lady's memory. (Of course, inevitably, they -- the nation, Bishops, Deacons, Deans, and politicians -- insisted and into the Abbey he went, his wishes be damned. Quite right too.) Yet Charles Dickens without English Protestantism is as impossible as a Catholic Bunyan. He believed much as Bunyan did. He professed and he protested much as Bunyan had, if not always with the same sunny earnestness, the surety of mercy or eagerness for martyrdom. Like Bunyan, he was loved and read by people who wouldn't have cared to see an Archbishop anywhere but at the end of a rope or kicked in the ass. Unlike Bunyan, Dickens could also make an Archbishop of Canterbury laugh. Quite a trick for someone who avoided priests and rewrote the Gospels for his children. Unlike Bunyan to one side and Swift at the other, Dickens walked with the crowd for the pleasure of it (save when they are blood-thirsty, though for a man who hated hanging, he went to not a few. A writer must have research and a journalist a story.) He may have been more comfortable talking to a sweep or a drudge, but he could manage a minute for the Supreme Head of the Church of England. Dickens is the first truly democratic genius in English letters, not for want of snobbery but for need of company. He might love The Lord Our God, or his Son anyway, and he might be flattered to dine with a Duke, he certainly was happy to kiss the chubby little hand of his Sovereign, but he wanted most to be loved, and needed to be loved as we all might require Grace, in abundance. Come one come all.

Why this furor to be loved? He was pretty confident that he had Jesus on his side. His children loved him even when he was impossible, even when he so cruelly turned their dim, dull, dear mother out. In later life he felt he needed, perhaps pathetically if not pathologically a young actress named Ellen Terran. He needed all of his friends, his contributors, his proteges, his sponsors. Above all, he needed his readers. More, he needed all of them to love him, not just his books. He read to them. He read himself to death for them, so that he might receive their love without the intercession of print. (He might have been happy being Homer, if one can imagine Homer in a loud, checked suit.) He was not always easy in his affections though, and his need was as great as his gift.

The easiest explanation of this relentless need to be loved is in that autobiographical fragment he shared only with his wife and his friend Forster. In it he told the story of his father's bankruptcy and imprisonment for debt. He described, aged twelve, being put out to work in a blacking factory, pasting labels on bottles in an unheated basement, surrounded by other grubby, hungry, hostile boys. His schooling, such as it had been, ended. And when his father's finances sufficiently recovered to escape the Marshalsea Prison, it was Charles' mother who insisted her son be kept working. Rough. So why did he abandon the memoir? Why conceal it from all but his nearest and dearest? I suspect that beyond the revelation of his family's fall from middleclass respectability, his personal sense of rejection may have been too deep a wound to expose. That was the real secret. He had not been loved, at least not enough. To write the truth of that he would have had to admit to having been abandoned, the small wages he earned of more value to his family than he was. Knowing poverty made him ambitious and uniquely empathetic to the poor, but to have been forsaken? To be less than Boz the Beloved of the English Speaking World? Too hard to admit. He was proud of what he'd made of himself. That he'd come from nearly nothing makes us admire him the more. Not necessarily so to him. Instead Dickens hid this earlier, shameful episode, and his own history as the unloved boy. The memory persisted though and it takes no literary detective to catch him letting that grubby, miserable little boy peep out here and there in the person of innumerable orphans and lonely children. He came nearest to telling the truth in the early chapters of David Copperfield. (His father famously appears therein as Wilkins McCawber. There is also more than a bitter hint of Charlie's old man in Mr. William Dorrit, among other fools and failures, fabulists, bankrupts, and weaklings. And of weak, greedy, distant, dead, or careless mothers there was no end. Dickens hardly ever spoke or wrote of his own mother by name.) The abandoned boy became the gentleman who would save them all or at least shame those who left children in want and ignorance.

Dickens liked establishing a character's character, good and bad, in just a line or two as they walk on. Amy Dorrit, for example "...so little and light, so noiseless and shy," etc. The reader is meant to know these people as soon as introduced, and remember them. Everyone is meant to be memorable even without being given their names straight-away -- "his nose came down and his mustaches curled up." This has made for much criticism down the years, of Dickens "grotesques," his effects and affectations, and the supposed unreality of his crowded fiction. When psychology was coined well after Dickens left the scene, he did not get high marks from his professional and professorial readers. Such critics, I always argue, do not take public transportation or they world know better. The wider one's acquaintance in the working world the less need of exaggeration. Perhaps now that we find ourselves in an age of political caricature and supremely inarticulate representation, an age of bullies and bosses and vociferous yahoos, of shockingly powerful charlatans and electable goons, we might be better prepared to accept Dickens' quicker insights and sharp definitions as truer than modern psychology's insistence on mystery. Beyond his remarkable ear and superhuman curiosity, beyond his obvious pleasure in the technical exercise of description, there is an underlying determination to summarize individual character by describing who we are by the way we are. Was he wrong? All very well for example to call oneself good (or a gentleman, or humble, or a patriot, or sensitive, or a Christian, or honest) but quite another to do good, which is after all Dickens' definition.

Reading Little Dorrit is to read Dickens at full cry. Good people do good, and not just to one another but even to those who may be undeserving. People may only seem to be benevolent because they look to be. Such fakes must be confronted and exposed. Silly people may tell the truth. Bad people can't always be made better. Some must be crushed. Some will escape. We must all be brave enough to do what we can to make things better where we can. Happiness is not guaranteed even to those who give it away, but the possibility of it is real. Only sentimental novelists are prepared to put all things right, bless 'em. The rest of us had better do better, damn it, particularly by the poor.

And everywhere in Dickens' big book, as in all of Dickens, there is English not only as, incredibly she is or was spoke, but also as only Dickens might write it; as rich in words and usage as Shakespeare, as righteous as Bunyan, as powerful as Hardy, and as funny as anyone who ever wrote in any language. His is a style that can be as beautiful as fine porcelain and as delicate, and as ample as a sturdy drainpipe. To not read and reread Dickens is to leave the language, our language, mine, to the stingy and the stupid and the lazy and the bad. They've enough of everything else, they've taken enough from the rest of us. They'll not have this. In the end all we need of him are his words. That's the gift. The rest is sidelines.