Well now, here it is at last. Part of it, anyway, the first part of three. The official hoopla started a couple of months ago, with magazine covers and the like, but for those of us in the book business, this thing has been coming on for a very long time indeed. Looks like it won't be complete anytime soon, either.

Well now, here it is at last. Part of it, anyway, the first part of three. The official hoopla started a couple of months ago, with magazine covers and the like, but for those of us in the book business, this thing has been coming on for a very long time indeed. Looks like it won't be complete anytime soon, either.We decided to mark the occasion, both of the centenary of the death of Samuel Langhorne Clemens, and the publication of the Autobiography of Mark Twain, Volume One, with a reading. Come November 16th, a couple of the usual suspects and myself will be reading from The Diaries of Adam and Eve: Translated by Mark Twain, as well as other material, some of it from this new book. Should be a grand affair, on a modest scale, but just grand, none the less.

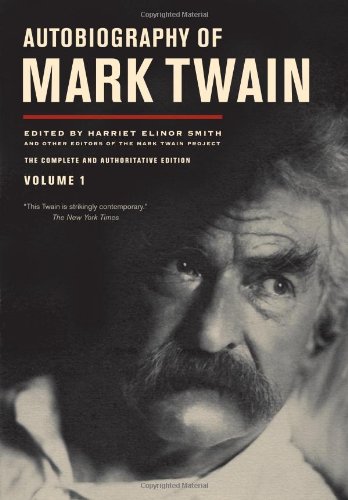

I only saw the new book for the first time at the PNBA convention in Portland, earlier this month. I'd anticipated something very like the book as is: big, impressively, not to say exhaustively annotated, well made, if almost impossibly clumsy to handle. At 10.3 x 7.4 x 2.6 inches, and weighing in at four pounds, the thing looks and feels like the kind of scholarly job typical of both the University of California Press, and The Mark Twain Project, admirable academic institutions, the pair of 'em. By such lights, this volume must represent not only years, if not decades of painstaking scholarship, by many hands, but also something of an editorial triumph, getting the thing down to just this first massive volume. One shudders to think what the eventual set of three will require by way of careful engineering, just to move it all from shelf to desk without aid of pulleys, levers and hired labor. Nonetheless, the price, at only $34.95, comes as a pleasant shock.

I was determined to read the thing without actually buying a copy, and failing that, without lugging the thing around for more than a day or two, but that resolution has already collapsed. I could justify the purchase by again mentioning the quite reasonable price, and the need to read up in preparation for our November event, but truth be told, I must always have known that I would sooner rather than later feel the need to own a copy. If the format has proved to be everything I dread in academic publishing, the book, once complete, promises still to be everything that Twain intended. The versions I've read already suffered mightily from fussing; first by Twain's family, then his estate, and his posthumous editors, etc., all of whom were really only following something like the author's own instructions, one way and another. It was, after all, Twain himself who instructed that the book be put in a drawer and kept there for one hundred years after his death. Still feel sure this book will prove to be worth the wait, if not the weight.

Those who've worked up the present edition have every reason to be proud of the restoration they've done. Considering both the state in which the editors found the original material, and what has been made of it heretofore, they've done a remarkable job. Such a reconstruction no doubt requires explanation, textual support and the like, and believe me, it's all here. In other words, the whole intellectual apparatus that, in this first volume at least, represents a full two thirds of the actual book, is necessary, and even has a certain fascination of it's own. This edition, clearly, is a story unto itself. Now if, as Twain famously advised a young writer, " Anybody can have ideas--the difficulty is to express them without squandering a quire of paper on an idea that ought to be reduced to one glittering paragraph" then this book may well represent the limitations of academic style as well as the best of contemporary critical understanding of the subject. There is no way to avoid the obvious drawbacks of unwrapping all this matter just to get at the Twain in the middle. This is not a genial publication. My hope had been that the editors might follow the example of Michael Holroyd's multi volume biography of G. B. Shaw, and put all the additional matter; notes and abstracts, and bibliographic materials and the rest, into a separate and concluding volume, and thus allow for readers to trust them unless and until moved by curiosity or necessity to consult that separate volume. (As a bookseller, I can vouch for a high percentage of the readers of Holroyd's masterly biography having purchased that last volume, even if it was never much read thereafter, except as it was meant to be, as a key to what came before. I used it just that way myself.) Had the editors of the Twain done such a thing, they might also have spared all of us the need to carry seven hundred odd pages around in order to read just the two hundred and fifty or so actually written by Twain. My hope now is that the editors of Twain, presumably after the third and final volume is printed, will someday offer the full text of the autobiography in an edition abridged of much if not most of the surrounding stuff, the idea being to allow for readers less interested in reading around and into the book and more interested in just reading the damned thing itself.

But until that does or does not happen, we have the book we get. Bellyaching aside, I am most glad to have it. If I can't bring myself to carry it in my bag each day, I've already found that it will not take me more than a day or two to read what I most want of it right here in my own house, where I can trust the table on which I've propped it. And yes, I'm already reading into some of the accompanying matter. Just tonight, I've been reading nothing but. I feel a bit like the baby who ignores the present to play with the box and the tissue it came in. Still, I think I might choose to prolong this much anticipated experience even if all I had was the autobiography itself. I've already had recourse, twice, since starting this book, to the edition of Twain's letters I already own.

My only real impatience at this point is with the sluggardly publication schedule for the rest of this project. I'm sure, by academic standards, the next two volumes are just racing to the bookstores. As a reader though, the idea that I won't see this thing through for years yet is maddening. I should, I suppose, be grateful for what I've got, and I am, truly.

I just wish I had more... and less, of course.

No comments:

Post a Comment