Another of the unexpected pleasures of my life online -- a life that I, like most of my generation never anticipated and for which I have become increasingly thankful as I find myself happiest now when home -- has proved to be how easy it is to find like-minded readers I would not otherwise have ever encountered. Working in a bookstore, I have had the happy recurrence of acquaintance with all kinds of enthusiasts with whom I share a fondness, say, for Emma in preference to Clarissa, and that has been an instant bond. With some customers, and not a few coworkers, I have come to share whole shelves together, and found in just this way, true friends. It's a very common usage now to speak of communities and mean not neighborhoods or towns, or even the old affinities of sect, but rather the commonalities of reading; most obviously in genre, but also, and better I think for not being so narrowly defined, just reading as either a pastime or, in many cases including my own, a way of life. I see it as such for me, and more so now that the idea that all culture is equally worthy, all expression valid, and all effort commendable would seem to be making every passing day the reading of books but one among the all but innumerable ways in which the good citizen-consumer may harmlessly entertain the stray hour -- neither more nor less, really, than knitting or shooting cartoon zombies -- both activities, I hasten to add, the practitioners of which I honestly hold in some awe as being so far outside my ken or skill. Even as good bookstores vanish, and the ideal of the book as the best and most affordable means of intellectual satisfaction continues to decline, the means of finding other readers, of discussing, recommending and reading books, as it were, together, has expanded so that now, I can read Austen with an Australian, a Greek and a woman from Des Moines, and all of us chat and exchange impressions, facts and whatnot in real, or nearly "real time," and none of us not in just a housedress. (Mine's a nightshirt, to be accurate, but it comes to the same thing as I'm wearing it in the daytime and with just slippers.)

I'm speaking again of Goodreads, of course, the social site with which I've recently become a little obsessed, but not to say that everything from Facebook to Twitter doesn't offer similar opportunities to connect reader with reader, at home and abroad. It's all good. I mean that. I know I can be seen here, often enough, and in the bookstore, to speak for just the Luddite and the print-stained, but I genuinely love the new immediacy and range that reading, writing and being online has provided to even musty old inklings like me. I confess myself ecstatic to read, for example, a nineteen year old girl from the other side of the world carefully explicating the universal appeal of Becky Sharp! Then there's another young reader -- this one Portuguese! -- with whom I have become, in this curious new way, fast friends through a shared affection for Tobias Smollett, through whose collected works the boy has just read! No lie! What, I ask you, are the chances of that?! What were the chances before this miraculous technological age of ours that I would ever have come across such a prodigy, or more accurately, that he might have found me?

For every favorite book I've bothered to look up on Goodreads and follow the thread of comments down, I have found, with real admiration, all kinds of enthusiastic readers, of every level of education, from all sorts of places, and of nearly every age, race or what-have-you, offering genuinely interesting reviews, remarks, posing questions and or answering them for other. (The group specifically devoted to reading the great Victorians, for a more organized example, is to my mind a model of good, democratic reading and full of very thoughtful help. Can't recommend them enough.)

There is also, of course, some shocking nonsense, but then when is there not in a public space? (Anyone who has ever hosted a reading in a bookstore or read a poem at a mic in a coffee-house will confirm the inevitable mad person, just vibrating to participate, come their turn or the Q&A.)

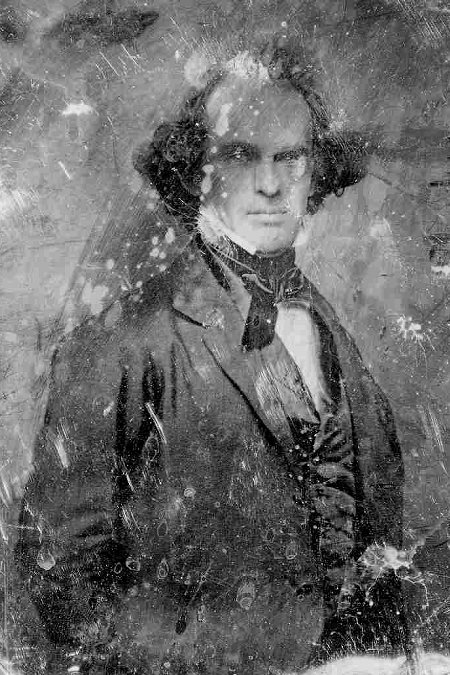

I must say, the strangest reviews I've read on my new favorite site? All to do with one novel, for which many readers seems to have neither any reverence nor points of reference. Very odd. Even those who've made a point of mentioning their previous reading of Hawthorne in school, and one must assume that meant either short stories and or The Scarlet Letter, would seem to find Hawthorne's style, and The House of Seven Gables specifically, pointless and confusing. I hadn't thought about this book, or the reading of it much since I had done years ago, when I myself was still a student. Rereading it now in middle age, I was struck most by how truly strange the book is, though, I find, in a wonderful way. There would not seem to have been an intellectual fad or technological innovation, from mesmerism to photography and the railroad that Hawthorne did not incorporate into his novel -- however ridiculous or barely understood -- and about which the novelist was not prepared the enthuse, all by way of contrast and celebration of the modern against the dead hand of history. If Hawthorne did not do specially well as a prophet of the coming age, he nevertheless created one of the most telling and atmospheric depictions of not only the dark and remoter origins of his country, but of the strangely violent clash, in even the remotest corners of the Republic of his own day, between the calcified and decaying traditions of the old world in the New, and the new age just then gathering steam, as it were, and barreling past everyone and everything in its path.

And yet! I was fascinated by the delicacy and affection with which he treats all the survivors of the disappearing New England: from the itinerant on the road to dear, dry old Hepzibah and her aesthetic ghost of a brother, and of course the country innocent, their angel, cousin Phoebe, the very last blossom & fruit of their rude and withered old stock. Curiously, the only truly modern men, the grasping Judge, and the young daguerreotypist upstairs -- as close as the novel comes to a hero -- are both dangerous; the one ruthless in his selfishness and the other, for all his weird science and powers of unearthly influence, little better than a magician, specially as compared to the solid, Christian virtues embodied in dear Phoebe and even the rigid devotion of Hepzibah Pyncheon to her name, and more and better, to her brother. Oh! And the other modern and most sympathetic, at least in my reading? That wonderfully greedy little Ned Higgins, the boy who would eat Creation, gingerbread by gingerbread, if they let him! Marvelous, dangerous boy!

Anyway, that's my gush, having just finished the book for only the second time. I don't remember what I made of it the first time I read it, or if I made much of anything of it at the time at all. (I can only hope that there are no surviving records of what I thought, about anything, at eighteen.) Obviously though, this is a complex novel, and not perhaps the easiest book then, I grant you, to talk or write about without considerably more study and or seriousness of purpose than I might ever bring to the task.

That said, I was still shocked by much of the posted comment on this book. Strong feeling, and much of it, frankly bad. But why so much? And why this book? Granting the usual contingent of snarky teenagers who may not think it wise to like things generally -- for fear of getting it wrong, again -- I can't quite understand the number of unhappy readers compelled to comment on this book.

I suspect that that word, "Romance," which Hawthorne so purposefully chose to describe his book, and the reputation this novel was awarded for weirdness by later, lesser talents like H. P. Lovecraft, have made much of the mischief for new readers. That word "Romance" has sadly shrunk in our time to just the thin stuff of sentimental sex, whereas for Hawthorne it would still have had all the thrilling mystery of history, myth and larger than life characters, and I suspect, already for a novelist of Hawthorne's generation, a pungent, not to say irresistible irony in what was already an unromantic and overwhelmingly materialistic country, or soon, as he quite rightly saw, his was to be. As for the weirdness, it's there, aplenty, but not as we've come to expect it; in gory spooks, butcher's paper, labyrinthine private mythologies and like childish silliness we think of now as "horror." Hawthorne is a serious artist, and even at his silliest, he doesn't stoop to such crude invention. Hawthorne's horror, and his romance, is all in the detailed description of place and people, in the influence of superstition and the potential for harm in even the greatest innovations of the dawning Industrial Age: it is in the Pyncheons then, and in us, and not in rotting timbers and weedy walks and dim rooms.

There are also lingering influences from the last century, and some of them like Freudianism, almost exclusively silly, that can still result in the most astonishing, and entertaining nonsense being posted. One gentleman from the Philippines, posting as Joselito, bless 'im, has a relatively lengthy review of Hawthorne's novel that has to be either a delightful, tongue-in-cheek parody of the ol' psychological criticism, or just a wildly inappropriate, and entertaining reading of the text, but either way the most hilarious bit of criticism I've come across since a certain little Big Noise out of Iowa defined the "lyric essay" as, well... anything written down.

Nevertheless, for all the unhappy comment and or unsympathetic reading of Hawthorne, the point is that one has only to look a little further down the line to find someone's comment that may inform, amuse and or suggest yet another kindred spirit:

Said one April Murphy, "My favorite quotation involving the reversal of Jonah and the Whale when the boy devours a whale-shaped cookie." -- There's our boy, Ned, again.

And next comes, Kimberly, with "Hawthorne has popped up in a couple of biographies I've read recently: he was part of Louisa May Alcott's circle; and his time in Paris was mentioned by David McCullough." -- Did not know either of those things. You get the idea.

I wish I could communicate better the pleasure to be had, for even the reader, like myself, inadequately versed in the history of New England, and Hawthorne, in reading such a masterful novelist let loose in such wonderful extravagance as this! No wonder Melville worshiped him and wanted him as his friend! I can only suggest any who haven't tried this book, or read it, as I hadn't, for thirty years, pick it up and allow themselves the pleasure of a visit to this marvelously strange corner, and major landmark of our literature. The House of Seven Gables deserves more visitors and finer sensibilities than the likes of what it seems sometimes to attract these days, myself included -- though, I had a grand time! And I've throughly enjoyed finding that I am far from alone.

No comments:

Post a Comment