There's no evidence that, as a boy, Sam Clemens aspired to be a writer. It does seem sure that however he might, he had every intention of one day being Mark Twain. Pretty much every American reader knows how young Sam spent his youth; wet from the knees, up to something on the river. Eventually, after being a boat pilot and a half-hearted prospector, he went into the newspaper business. Had he made a career of journalism, I don't doubt Mark Twain, as he was by then, might still be known to us, but again, he aimed at something other and became a writer. And like all great writers and indifferent journalists, Twain learned early to bury the lead. With the perfect instinct of the born humorist -- the noun to which he then intended his new name should be attached -- Twain knew to pull his punchlines, jab but not signal his shots, how to feint, bob and weave before the knock-out came; how to write, in other words, rather than tell. This is disastrous when reporting the news, but vital to any story intended to last longer than the time it takes to read it. (And a lesson still to be learned by many a young writer, and more than a few not so young and in their transient way successful writers today.)

The last man to honestly write the word "humorist" under occupation on his passport probably went into the ground in roughly the same shift as, say, Art Buchwald. This because, by the close Twentieth Century, the term had become synonymous with a purveyor of the kind of harmless, painfully mild amusement intended not to make the Rotarian spill his morning coffee. Back in Twain's day, humorists were made of sterner stuff; folksy, crude, never shy of the racist jibe, the dialect joke -- crackers, to put it plain. (Think, at best, Petroleum V. Nasby.) Today, both the rough and the smooth are about equally unreadable. But the humorist in his heyday was something of a force, as close as the then adolescent nation could come to the satirist; a wit among clowns, and yes, a comedian before comedy stood up. Twain himself in latter life, to remake the fortune he'd lost investing in a new typesetter-technology that could never be made to work, took to lecturing, as Dickens had before him. There was real money to be made then by the celebrated author on the stage. Unlike Dickens, Twain did not so much read or act as talk and might rightly be said to be the father the modern comic. By then, he had been making his readers laugh, and love him, for a very long time. In the flesh he was, if anything, even funnier. A fortunate marriage had not so much sobered as refined him, and while, again like Dickens, Twain was never an intellectual, he had that uniquely Nineteenth Century capacity not just to work, but to learn, and teach. (I'll say again, the influence of his wife, Olivia Langdon Clemens, was singular and salutary. She was not only the first and best critic of all his best work, but also the spirit that did most to expand his affections, distill his thinking, inform his politics, and improve the general condition of his soul. She made a man of him. More even than literary friends like William Dean Howells, it was Livy who cultivated that confidence and seriousness that made Twain a good and not just a great writer.)

What separates the satirist from the comedian is not their materials or tools, but the purpose to which these are turned. While Twain was almost never not funny, over time fun ceased to be all he meant to make. His greatest novel -- our greatest novel -- may have started out to be just the further adventures of a character both the author and his audience had come to love, but at some point, dissatisfied, Twain put Huck away unfinished. When he took him out again, the man who'd written The Adventures of Tom Sawyer was not the man who would finish what became The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Anyone reading these books one after the other will not need me to point out the change from one to the next; the first is a comedy, and a classic, the second a masterpiece.

Whatever the technical improprieties in that book: the improbabilities of plot, the slack joke here and there, the sometimes wild shifts of tone and intention, ultimately what makes it great is what made Twain good. When he pushed Huck and Jim out onto that river, I don't believe he initially intended that they should go so far. Things may have drifted for awhile, but, when Twain came back to the raft ag'in, Huck Honey, the humorist, the satirist, was now the novelist and this novel was different in kind from anything he'd ever written. His timing was subtle, from long practice, and his burlesque was still funny, but he was a better and an angrier man than he'd been before, a writer unlike anything we'd ever seen, and he made a character we might have thought we knew already into something like our national autobiography. It is still the most remarkable achievement in American letters. Appropriately mongrel, come to that.

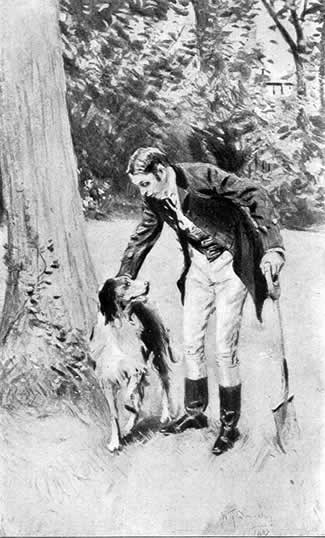

Which brings me, at last, to the little mutt the reader will find reprinted as the first book in the Usedbuyer's Bookshelf. Not to make too much of it, but be warned: this very short dog story, for all its familiar charm, and funny as it still is, bites. Twain wrote it to promote a cause that was dear to him. He loved animals, so long as they were not too long upright, and dogs, he felt, were nearer to being good just of themselves than most. Twain despised any unthinking cruelty as being no more forgivable for being so, and this story is as near to being a pure polemic as such a fundamentally funny man could make it. Works all the better for that.

We take it up again at the bookstore as part of a reading series meant to remind those of us who fancy ourselves grown that there's something to be said still for innocence, and still a great deal to be learned from a dog.

We reprint it so that the lesson might not be lost even on those unable to attend the event. Bears repeating, and rereading, even now.

Human beings, it seems, can't be taught a damned thing, hardly.

No comments:

Post a Comment