"I hold any writer sufficiently justified who is himself in love with his theme." -- Henry James

Wednesday, August 31, 2011

Daily Dose

Tuesday, August 30, 2011

Daily Dose

From For Your Eyes Alone: The Letters of Robertson Davies, edited by Judith Skelton Grant

From For Your Eyes Alone: The Letters of Robertson Davies, edited by Judith Skelton Grant

DOSTOEVSKY

"Nevertheless, one cannot not read him, and I have always been intrigued by his assertion that he learnt much from Dickens. What can that have been?"

From a letter to Elisabeth Sifton, dated December 2, 1991

Monday, August 29, 2011

Daily Dose

From The Complete Works of W. H. Auden: Prose, Volume II, 1939 - 1948, edited by Edward Mendelson

From The Complete Works of W. H. Auden: Prose, Volume II, 1939 - 1948, edited by Edward Mendelson

KAFKA

"Had one to name the artist who comes nearest to bearing the same kind of relation to our age that Dante, Shakespeare and Goethe bore to theirs, Kafka is the first one would think of."

From The Wandering Jew, a review of three Kafka titles in English

Sunday, August 28, 2011

Daily Dose

From The Complete Works of W. H. Auden: Prose Volume II, 1939 - 1948, edited by Edward Mendelson

From The Complete Works of W. H. Auden: Prose Volume II, 1939 - 1948, edited by Edward Mendelson

MARIANNE MOORE

"The endless musical and structural possibilities of Miss Moore's invention are a treasure which all future English poets will be able to plunder. I have already stolen a great deal myself."

From Beauty Is Everlasting, a review of Nevertheless, by Marianne Moore

Saturday, August 27, 2011

Daily Dose

From The Complete Works of W. H. Auden: Prose and Travel books in Prose and Verse, Volume I, 1926 - 1938, edited by Edward Mendelson

From The Complete Works of W. H. Auden: Prose and Travel books in Prose and Verse, Volume I, 1926 - 1938, edited by Edward Mendelson

LIKE

"We write first and use the theory afterwards to justify the particular kind of poetry we like and the particular things about poetry in general which we think we like."

From Pope

Friday, August 26, 2011

Daily Dose

From The Complete Works of W. H. Auden: Prose, Volume III, 1949 - 1955, edited by Edward Mendelson

From The Complete Works of W. H. Auden: Prose, Volume III, 1949 - 1955, edited by Edward Mendelson

JOHNSONIANS

"It cannot be too strongly emphasized that Johnson and Boswell are not the same person and that Johnson is much too good and interesting a writer to be left to the Johnsonians."

From Man before Myth, an otherwise positive review of Young Sam Johnson, by James L. Clifford

Thursday, August 25, 2011

Daily Dose

Wednesday, August 24, 2011

Daily Dose

Tuesday, August 23, 2011

Daily Dose

Monday, August 22, 2011

Daily Dose

From Selected Letters of James Thurber, edited by Helen Thurber & Edward Weeks

From Selected Letters of James Thurber, edited by Helen Thurber & Edward Weeks

CLAIMS

"I don't know whether Cruikshank, who illustrated Dickens, ever drew for Punch or not, but I think not; anyway, in reading a sketch on him I learned that in old age he claimed to have written Oliver Twist. My mother's Uncle Milt claimed in his old age to have written 'Dixie.' So it goes."

From a letter to E. B. White, dated Woodbury, Connecticut, Fall 1938

Sunday, August 21, 2011

Daily Dose

Saturday, August 20, 2011

Daily Dose

Friday, August 19, 2011

Daily Dose

From A Book of Sibyls: Mrs. Barbauld, Miss Edgeworth, Mrs. Opie, Miss Austen, by Anne Thackeray Ritchie

From A Book of Sibyls: Mrs. Barbauld, Miss Edgeworth, Mrs. Opie, Miss Austen, by Anne Thackeray Ritchie

THESE PEOPLE

"These people belong to a whole world of acquaintances, who are, notwithstanding their old fashioned dresses and quaint expressions, more alive to us than a great many of the people among whom we live."

From Jane Austen

Thursday, August 18, 2011

Daily Dose

Wednesday, August 17, 2011

Daily Dose

Tuesday, August 16, 2011

Daily Dose

From Scenes of Childhood, by Sylvia Townsend Warner

From Scenes of Childhood, by Sylvia Townsend Warner

STOP

"English people don't visit country churches now as they used to when I was young. This is partly because modern cars are so difficult to stop."

From A Winding Stair, a Fox Hunt, a Fulfilling Situation, Some Sycamores, and the Church at Henning

Monday, August 15, 2011

Daily Dose

Sunday, August 14, 2011

Daily Dose

FROM FANNY STEVENSON

"You told me when we left England that if we found a place where Louis was really well, to stay there. It really seems that anywhere in the South Seas will do."

From a letter from Mrs. R. L. Stevenson to Sidney Colvin, dated Apia, January 20th, 1890

Saturday, August 13, 2011

Daily Dose

Friday, August 12, 2011

Our First Effort

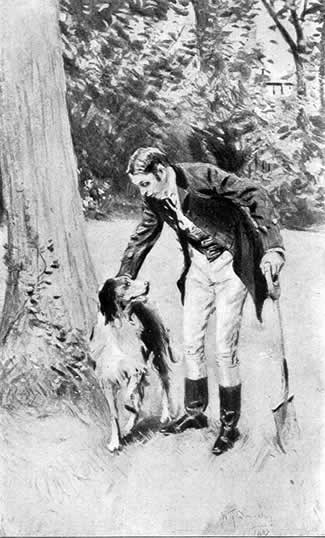

Here then the evidence of our first effort. The brilliant young Anna Micklin, new pilot of the bookstore's EBM, Homer, has made our little scheme real. Inside, the text of Twain's story, plus the new introduction -- see below -- by me. Outside, my pencil sketch and her skills to make the cover. A slight thing, but our own.

As can be seen in the rather wonky scan at right, the title page announces this little number "as part of the Dog Days of Summer Reading Series," and so, indeed, it is. Tomorrow evening, at six, Michael Wallinfels will be reading this very story at the bookstore. My sincere hope is that someone besides me shows up to hear him. He's quite good, you know, and not hard to look at, come to that. Time permitting and anyone lingers after the dazzling Michael has had his turn, I will have a go at P. G. Wodehouse's story, "The Mixer." Meanwhile, whatever happens with tomorrow's show, here's evidence for you of our commitment to bring new/old books to the attention of the people, and or their pets.

As can be seen in the rather wonky scan at right, the title page announces this little number "as part of the Dog Days of Summer Reading Series," and so, indeed, it is. Tomorrow evening, at six, Michael Wallinfels will be reading this very story at the bookstore. My sincere hope is that someone besides me shows up to hear him. He's quite good, you know, and not hard to look at, come to that. Time permitting and anyone lingers after the dazzling Michael has had his turn, I will have a go at P. G. Wodehouse's story, "The Mixer." Meanwhile, whatever happens with tomorrow's show, here's evidence for you of our commitment to bring new/old books to the attention of the people, and or their pets.

Even if the talented Michael reads only to me, and I to him tomorrow, this little book represents a real beginning, I think. New technology like the Espresso Book Machine has such exciting possibilities. One has only to investigate them to see the almost limitless potential for bookstores and their customers, for new readers of old books, new and established writers looking to have a go at affordable and attractive self-publishing, etc., etc. Now it's true, I haven't much to do with all that last, as that's Anna's corner, but as you can see, our Homer is capable of accommodating even the more eccentric projects of an old print-junky like me.

As I say, it's a good start. So, even if you can't attend our reading this Saturday, if you are any kind of a bibliophile, do please pay a visit to any of the independent bookstores now operating one of these remarkable machines. Besides ours at the University Book Store, right here in the Northwest there's another at Third Place Books, and yet another at Village Books in Bellingham. Well worth investigating all three. All manner of interesting things happening, believe me.

Daily Dose

Thursday, August 11, 2011

Daily Dose

From Doggerel: Poems about Dogs, selected and edited by Carmela Ciuraru

From Doggerel: Poems about Dogs, selected and edited by Carmela Ciuraru

O HAPPY DOGS OF ENGLAND

O happy dogs of England

Bark well as well you may

If you lived anywhere else

You would not be so gay.

O happy dogs of England

Bark well at errand boys

If you lived anywhere else

You would not be allowed to make such an infernal noise.

By Stevie Smith

Wednesday, August 10, 2011

Why Dogs Should be Funny in the First Person, Yet Come to a Sad End

There's no evidence that, as a boy, Sam Clemens aspired to be a writer. It does seem sure that however he might, he had every intention of one day being Mark Twain. Pretty much every American reader knows how young Sam spent his youth; wet from the knees, up to something on the river. Eventually, after being a boat pilot and a half-hearted prospector, he went into the newspaper business. Had he made a career of journalism, I don't doubt Mark Twain, as he was by then, might still be known to us, but again, he aimed at something other and became a writer. And like all great writers and indifferent journalists, Twain learned early to bury the lead. With the perfect instinct of the born humorist -- the noun to which he then intended his new name should be attached -- Twain knew to pull his punchlines, jab but not signal his shots, how to feint, bob and weave before the knock-out came; how to write, in other words, rather than tell. This is disastrous when reporting the news, but vital to any story intended to last longer than the time it takes to read it. (And a lesson still to be learned by many a young writer, and more than a few not so young and in their transient way successful writers today.)

The last man to honestly write the word "humorist" under occupation on his passport probably went into the ground in roughly the same shift as, say, Art Buchwald. This because, by the close Twentieth Century, the term had become synonymous with a purveyor of the kind of harmless, painfully mild amusement intended not to make the Rotarian spill his morning coffee. Back in Twain's day, humorists were made of sterner stuff; folksy, crude, never shy of the racist jibe, the dialect joke -- crackers, to put it plain. (Think, at best, Petroleum V. Nasby.) Today, both the rough and the smooth are about equally unreadable. But the humorist in his heyday was something of a force, as close as the then adolescent nation could come to the satirist; a wit among clowns, and yes, a comedian before comedy stood up. Twain himself in latter life, to remake the fortune he'd lost investing in a new typesetter-technology that could never be made to work, took to lecturing, as Dickens had before him. There was real money to be made then by the celebrated author on the stage. Unlike Dickens, Twain did not so much read or act as talk and might rightly be said to be the father the modern comic. By then, he had been making his readers laugh, and love him, for a very long time. In the flesh he was, if anything, even funnier. A fortunate marriage had not so much sobered as refined him, and while, again like Dickens, Twain was never an intellectual, he had that uniquely Nineteenth Century capacity not just to work, but to learn, and teach. (I'll say again, the influence of his wife, Olivia Langdon Clemens, was singular and salutary. She was not only the first and best critic of all his best work, but also the spirit that did most to expand his affections, distill his thinking, inform his politics, and improve the general condition of his soul. She made a man of him. More even than literary friends like William Dean Howells, it was Livy who cultivated that confidence and seriousness that made Twain a good and not just a great writer.)

What separates the satirist from the comedian is not their materials or tools, but the purpose to which these are turned. While Twain was almost never not funny, over time fun ceased to be all he meant to make. His greatest novel -- our greatest novel -- may have started out to be just the further adventures of a character both the author and his audience had come to love, but at some point, dissatisfied, Twain put Huck away unfinished. When he took him out again, the man who'd written The Adventures of Tom Sawyer was not the man who would finish what became The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Anyone reading these books one after the other will not need me to point out the change from one to the next; the first is a comedy, and a classic, the second a masterpiece.

Whatever the technical improprieties in that book: the improbabilities of plot, the slack joke here and there, the sometimes wild shifts of tone and intention, ultimately what makes it great is what made Twain good. When he pushed Huck and Jim out onto that river, I don't believe he initially intended that they should go so far. Things may have drifted for awhile, but, when Twain came back to the raft ag'in, Huck Honey, the humorist, the satirist, was now the novelist and this novel was different in kind from anything he'd ever written. His timing was subtle, from long practice, and his burlesque was still funny, but he was a better and an angrier man than he'd been before, a writer unlike anything we'd ever seen, and he made a character we might have thought we knew already into something like our national autobiography. It is still the most remarkable achievement in American letters. Appropriately mongrel, come to that.

Which brings me, at last, to the little mutt the reader will find reprinted as the first book in the Usedbuyer's Bookshelf. Not to make too much of it, but be warned: this very short dog story, for all its familiar charm, and funny as it still is, bites. Twain wrote it to promote a cause that was dear to him. He loved animals, so long as they were not too long upright, and dogs, he felt, were nearer to being good just of themselves than most. Twain despised any unthinking cruelty as being no more forgivable for being so, and this story is as near to being a pure polemic as such a fundamentally funny man could make it. Works all the better for that.

We take it up again at the bookstore as part of a reading series meant to remind those of us who fancy ourselves grown that there's something to be said still for innocence, and still a great deal to be learned from a dog.

We reprint it so that the lesson might not be lost even on those unable to attend the event. Bears repeating, and rereading, even now.

Human beings, it seems, can't be taught a damned thing, hardly.

Daily Dose

Tuesday, August 9, 2011

Introducing the Usedbuyer's Bookshelf

It's not necessarily the interesting books we buy. Not to say anything against the used books we do, but most of them you might find on the shelf right next to the new copy, just alike in all but price. That's the ideal, anyway. The point is to buy what will sell, and when it does, buy another just like it and sell that. That's not all we do at the used books buying desk, but doing just that, consistently, at a fair bid and a good price, is what helps to keep the lights on. It's not all bestsellers -- in fact, after roosting for weeks or months on the lists, there's nothing so likely to suddenly drop down dead in their hundreds and rot where they fall -- but for the most part what's wanted used is what's still selling new; what's popular, useful, standard, well reviewed; producing authors with loyal followings, addictive genre-corn, commercial fiction, fashionable opinion, recyclable history, practical advise, and yes, the Classics. Please note the upper there, as it is the lower-case classic; the minor works of the major authors, the major titles of lesser talents, that are often the most interesting old books I see.

A "rare modern first" or a "fine" binding are used in the business as terms of art, though the language is nothing if not commercial, and so subjective and haphazardly applied by most sellers, in and out of the trade, as to be largely meaningless. A proper antiquarian bookseller, after much study and careful consultation of the arcana, the Internet and the credulity of his customer, may advertise, at some risk, admittedly, any damned thing he or she might own as being somewise special. (A note to the amateur collector: the more sesquipedalian the dealer or description of the book, the likelier you, my honest friend, will pay too much.) Any true bibliophile might like a nice leather binding and a bit of tasteful gilding, a lovely old book, stoutly stitched, the pages still uncut and unread. For the devoted collector, no price may be too high for that missing work or never before seen variant edition. I understand something of the fascination. I have myself succumbed often enough to a pretty book. But an interesting book, in the sense I mean it here, needn't be pretty, or fine, or rare, needn't be anything much, come to that, but good, most often old and out-of-print and yet, new to me.

And what would tell me this old book, as opposed to that one, might be good, might be better worth reading, say, than anything out of the box after box after bin of newer titles that come every day across the buying desk?

Might be so simple a thing as an almost recognizable name; some title or author met elsewhere, though who remembers where? Some reference made, in an old review, or the vague recollection that this one knew that one and that one I've always liked. It might be quote that's not quite right, but familiar, or it might be heard everywhere, but from someone other, after all, than Churchill or Wilde or Twain. "So, that's who said that!" The Internet is a seemingly boundless source of quotation, I've discovered, and not all of it wrong. The problem there is that while there must be hundreds of places online to find who said what, there's almost nothing to say where or when or why. Even more frustrating, going just by what a simple search will suggest, it seems the same ten or twelve men said exactly the same five or six things, and always on just theses topics, no matter where you find them. Turns out, that's not true. The textbook anthologies must answer for this as well, as always the same short poem, the same truncated prose is reprinted and reprinted, however much the author might have done, whatever else he or she wrote, until at last the poet is but those same five lines, the novelist that one short story, the critic one review, the philosopher one thought -- though that a complex one to be fair -- and the wit but the one bitter remark. Interesting old books are interesting then because they promise something familiar, but more.

Open a book by a once celebrated poet now never read or, if at all, then only in some ponderously comprehensive history of literature. Run your thumb down the list of first lines and see if somewhere in that slim volume of poems there isn't some half-remembered song from childhood, the title of a mystery novel or two, some phrase just used ironically on the radio that day. See? Take up some charming old history and see if just the summaries of each chapter, without reading so much as a sentence beside, do not tell a better story than half the stack of histories on the display table of new nonfiction. Try the titles in an old book of English or American personal essays, and tell me you shouldn't care to know something more about the origins of roast pig, or what an essay "On Nothing" might be.

The traditionally capitalized Classics can usually see to themselves, at least in good company. If you didn't read them in school, or even if you did, but haven't taken them up again -- to read them properly -- with adult eyes, knowing you'll not be tested, with no one to impress now but yourself, your dog, say, or your spouse, then, sadly, I must tell you plainly, you never will. Doesn't make you a bad person. Doesn't necessarily even make you a foolish one, though you'll be and sound no wiser to admit such a thing. Perhaps, as you say, you've always meant to, but... you're very busy. If I might in this rude way shame you into reading something great, then by all means, prove me wrong. Start at the top of the pile. The interesting books I mean to suggest are not then meant for you, and there's no shame in that. Busy people really wouldn't have time for the kind of books I mean, however slight the books might be, not when there's Vanity Fair yet to be got to, and David Copperfield, and Emma yet to meet. Go on then, with my blessing -- though why you should need such an impertinence from me to set you going, I can't think.

But anyone with a taste for less traveled roads, or looking to find some pleasant stopping-off-place for an hour or an afternoon, I propose to put you in the way of a few unsuspected attractions, neglected views, places, as the guide might say, "of interest."

My problem with interesting old books is that they are not so easy to recommend without showing them, and I'm afraid I make it a policy not to loan my books. (It's all well and good to loan some paperback novel 'round your book club, so long as you're content to get it back in a state bearing little resemblance to the book you bought. I'm sorry, but I'd rather you borrowed my car or my cat before I'd let you borrow my books. ((My car by the way is filthy, and I do not keep a cat, as it happens.))) The bookstore where I work, a mix of old and new, has provided me with the solution.

Nearly any interesting old book, long enough out-of-print, we may now print again. I propose to do just that with at least the few old books I should specially like to see find the few, select readers I think they deserve. To each of these, my idea is to attach this essay, by way of general introduction to the scheme, and then add an even briefer note, unique to each, explaining my selection of the title. Perhaps a reading or an anniversary, a birthday or some new publication or renewed interest in the subject might justify reprinting a particular title or author. Some eccentricity of my own may be all the excuse I need. We shall see.

To each reprinted book, with the help of my more sophisticated coworkers, I hope to attach a new and attractive cover -- I to contribute some pencil-sketch, presumably of the author, my friends to make something presentable from that. As to any additional matter to be added, before or aft to the text, I make no claim of anything I might write, this ramble included, to literature. My role is simply that of the bookseller. I mean not to press some obscure little book into unsuspecting or unwilling hands, but rather just to add a little novelty to the copies we lay out as "new". I expect no one to buy a book because I've inserted myself between the reader and the work. The interest in these books, I am sure, will never be me, even if the first interest in them for what might be many years was, so far as I know, mine.

As with any such Quixotic undertaking of mine, I do not foresee much success for this bookshelf I hope to build. As you can see, unlike the writers I would celebrate and the works I would promote, there's little craft and less art than might be needed to guarantee the stability of this little enterprise of mine even so long as it may take to prop one title with the next. But what is there to lose in trying?

An interesting book, however unadorned or even ugly, however old or obscure, must, I firmly believe, find it's inevitable reader, just as these books found me. All I can do is put them out again where readers might see them. So...

This might be a book you may not know and one I think you will find interesting. I did.

Daily Dose

Monday, August 8, 2011

Daily Dose

Sunday, August 7, 2011

Daily Dose

Saturday, August 6, 2011

Daily Dose

Friday, August 5, 2011

Daily Dose

From William Cowper's Letters: A Selection, edited by E. V. Lucas

From William Cowper's Letters: A Selection, edited by E. V. Lucas

MY DEAR COUSIN

"You ask me how I like Smollett's Don Quixote? I answer, well, -- perhaps better than any body's; but having no skill in the original, some diffidence becomes me."

From a letter to Lady Hesketh, dated The Lodge, May 6, 1788