After visiting a few of the more glorious ministers of bookselling in the city during my friend's recent visit, coming home from a trip to the suburbs where we'd been to see a big, silly movie, we took the opportunity to drop in to an altogether more humble little book shop on our way. This bookstore is nestled between a Japanese luncheonette and a purveyor of inexpensively hideous home decoration. There is little or nothing to recommend the place: it is part of a national chain of used books shops, some considerably grander than the one described here, but all of them having in common the same atmosphere of shiftless indifference to alphabetization, the condition and selection of their stock, and any suggestion of an an undemocratic preference for good books to bad. My experience of the buyers in these shops is that they are invariably polite and helpful, some few quite knowledgeable, but all so badly paid and abstractly managed that the best books, or at least the most valuable, tend to be spirited under the buying desks, to be purchased at a discount on the dollar and sold for profit privately elsewhere, online or to better sellers. So at least I've heard for years. Notorious in the trade for the sharp parsimony of what they pay for their books, they are nonetheless an occasional boon to the collector, as they can not be bothered to research what they sell, and what they do not recognize as valuable tends to drift out to the shelves with the popular trash and the forgotten old flotsam of yesteryear, where treasures might then be found, under-valued and at prices unlikely to be met with in better run operations. As the company presumably makes its money from paying sellers and employees badly, from remainders, cheap, reissued CDs, secondhand DVDs, and volume, what ends up in the locked cases tends to be autographed copies of forgettable modern fiction, beautifully bound junk, faded erotica and the quaint memorabilia of popular culture: "rare" books on The Beatles, early Crumb comics and the like. But the best things in these bookstores, I've found, are to winkled out in neglected corners.

After visiting a few of the more glorious ministers of bookselling in the city during my friend's recent visit, coming home from a trip to the suburbs where we'd been to see a big, silly movie, we took the opportunity to drop in to an altogether more humble little book shop on our way. This bookstore is nestled between a Japanese luncheonette and a purveyor of inexpensively hideous home decoration. There is little or nothing to recommend the place: it is part of a national chain of used books shops, some considerably grander than the one described here, but all of them having in common the same atmosphere of shiftless indifference to alphabetization, the condition and selection of their stock, and any suggestion of an an undemocratic preference for good books to bad. My experience of the buyers in these shops is that they are invariably polite and helpful, some few quite knowledgeable, but all so badly paid and abstractly managed that the best books, or at least the most valuable, tend to be spirited under the buying desks, to be purchased at a discount on the dollar and sold for profit privately elsewhere, online or to better sellers. So at least I've heard for years. Notorious in the trade for the sharp parsimony of what they pay for their books, they are nonetheless an occasional boon to the collector, as they can not be bothered to research what they sell, and what they do not recognize as valuable tends to drift out to the shelves with the popular trash and the forgotten old flotsam of yesteryear, where treasures might then be found, under-valued and at prices unlikely to be met with in better run operations. As the company presumably makes its money from paying sellers and employees badly, from remainders, cheap, reissued CDs, secondhand DVDs, and volume, what ends up in the locked cases tends to be autographed copies of forgettable modern fiction, beautifully bound junk, faded erotica and the quaint memorabilia of popular culture: "rare" books on The Beatles, early Crumb comics and the like. But the best things in these bookstores, I've found, are to winkled out in neglected corners.I acquired my wonderful set of Stevenson in one of these places, under inches of dust and thrice "marked down." Likewise my handsome set of J. M. Barrie, which I bought during a clearance sale, with a coupon, at something like a quarter of it's already low, marked price. I reformed my set of Virginia Woolf's essays by hunting through another location, collecting volumes one and three from a box on the floor in front of belles-lettres, volume two from the shelves of fiction, and the last volume from the poetry section! The set was clearly from a single owner, his name carefully written inside each. All four volumes had been priced, and shelved by different hands, presumably without reference to their original purpose, their content or even the title on the covers. I paid an exceptionally low price for those books. Over the years, shopping regularly in all the locations I've found in the area, I have bought more great books at less than their value from this chain than from any other, better used bookstore I frequent.

As a person in the trade, I shake my head every time I enter these places, but as a collector of unlikely authors and rare old books, I am very grateful for their consistent negligence. I could never have afforded half the books I've found in these shabby places if anyone had bothered to price them properly. Here then, I humbly thank the clerks, buyers and proprietors for a bad job, well done.

The problem with such places is, having found a lost jewel in the rubbish-tip, one is drawn back again and again in hopes of finding another. Too often there is simply nothing to be found. Going into the little suburban mall store again with my friend, I warned him of the general worthlessness of the stock and the disorder that can make shopping there a trial, and I'd steeled myself for disappointment. No sooner was I in front of the shelves of "Old But Interesting" than I chanced on a four volume set, for twenty dollars, of The Collected Essays and Papers of George Saintsbury, 1875 - 1923. Happiness!

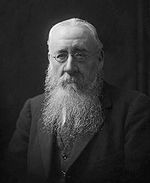

George Saintsbury was one of the greatest of that extinct species, the English Man of Letters. A gentleman with only a second-rate degree, and few prospects, he went into journalism and reviewing, did every kind of political and artistic hack-work for the Tories, and in the meanwhile mastered the classic and contemporary literature of no less than three living languages, introduced the first serious and popular criticism of such major artists as Flaubert in English, and wrote some of the best critical essays of his day. He went on to write a textbook of English literature that saw generations through the subject, became, at last a respected academic chairman, a revered and much lampooned figure as the best read man of his time, and eventually returned to literary journalism, writing some of the best, and most entertaining critical essays I've ever read. Sainstbury was fiercely opinionated, very much of his times, and something of a donnish scold. He was also eminently readable, full of enthusiasms, and, at least by his own, peculiar light, always scrupulously fair. Reading his essays on Hazlitt, Thomas Moore, and Leigh Hunt, all at a go, one feels the full weight of Saintsbury's authority; he has read everything there was to read by about each man, knows what he likes best in each, and as dismissive as he is of what he considered bad or mediocre, he is insistent that what is best is so very good indeed that the reader would do well to seek it out immediately, or risk losing a rare opportunity to read the best English written. If much of his severest criticism is premised on assumptions of patriotism, propriety, and what constitutes appropriate subject for literature, all of this is now forgivable, even for the most part amusing. In his presumption that the sun could never really set on the great English gentleman and all his works, Saintsbury spoke and wrote very much for his own. Dead now, don't you know. No doubt the neglect he has suffered since the Second World War has a great deal to do with the extinction of his kind of criticism, and with the failure of subsequent generations to accept his or any kind of authority, but it is also to do admittedly with politics. He was a loud fool about Ireland, for instance, introducing the subject too often and into essays where it did not belong. But for anyone wanting a genial and thoughtful review of great writers by a remarkably well read, and very good writer indeed, Saintsbury is worth seeking out. (His few regular readers nowadays being wine drinkers as he was himself a winebibber of lasting reputation and his writing on the subject still very much read. But look for his literary essays where you can.)

The edition I bought is a faded but otherwise well made thing from J. M. Dent & Sons, LTD, 1923. The introduction is by the author and this is his selection of his essays, organized according to his plan. In each of the four volumes I have already, as I said, found much to enjoy, and from Saintsbury's suggestions, I have already made many notes of what to read next in some favorite authors, but this time with the great critic as my guide.

And that is what a truly great teacher ought to do -- make one want to read more.

As for the shop in which I found my Saintsbury, I can only, again, say thanks for having the sense to buy these books, and the lack of sense to price them according to their value. I am most grateful.

No comments:

Post a Comment