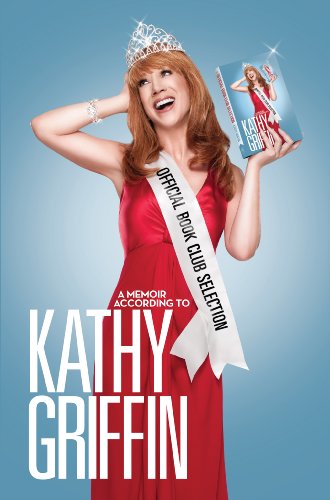

Okay, here's the thing, when I mention Kathy Griffin to certain of my friends, all of them women, there is often a moment's passing disapproval, and then I am... indulged. I don't quite know how else to explain the reaction. It isn't as if eyes are rolled, or anyone walks away. I tell my little anecdote taken from "My Life on the D List," or relay something that made me howl from her stand-up, or now I might even share a direct quote from Kathy's new book, Official Book Club Selection: A Memoir According to Kathy Griffin, and the best I seem to get from many of my girlfriends is a little chuckle, or a pained smile. Good women, all of them, mind you, and evidently quite fond of me, but unconvinced. I do not understand this.

Okay, here's the thing, when I mention Kathy Griffin to certain of my friends, all of them women, there is often a moment's passing disapproval, and then I am... indulged. I don't quite know how else to explain the reaction. It isn't as if eyes are rolled, or anyone walks away. I tell my little anecdote taken from "My Life on the D List," or relay something that made me howl from her stand-up, or now I might even share a direct quote from Kathy's new book, Official Book Club Selection: A Memoir According to Kathy Griffin, and the best I seem to get from many of my girlfriends is a little chuckle, or a pained smile. Good women, all of them, mind you, and evidently quite fond of me, but unconvinced. I do not understand this. Now if I were to try to convince some thoroughly straight fellow that he really needed to appreciate the nuanced acidity of, say, Kathy's vendetta against Ryan Seacrest, I could completely understand even the nicest, brightest, hippest heterosexual man meeting any such suggestion with complete indifference. Not all straight guys, mind you. Somewhere there have to be straight male fans of Kathy Griffin. The woman herself may have largely written off the demographic, but I have known boys who prefer girls, who never the less had the occasional taste for guerrilla camp. Lord knows, I've known plenty of guys who could appreciate a good dick joke. Nobody better. But while Griffin is an artist with vulgarity, a perfect shit-storm of hyperbolic blue butch, I suspect her impish insistence that her dick is bigger than yours may be off-putting for some guys. She is flatly contemptuous of any and all assumptions of gender inequality, and unlike other straight, female comedians, she never plays up to masculine vanity by hinting, much as it might piss her off, she just can't live without a man. Instead, she consistently parodies the aggressive sexual immaturity that is something of a watchword among male comics, by insisting that there is little enough to most men that might not best be employed flat on their backs. Men are not used to being so casually objectified, straight men anyway, and I don't think they quite appreciate being treated so roughly, by a girl. I suppose she rather hurts their feelings.

Kathy's whole comedic persona is built up from just that premise of seemingly unselfconscious presumption. She does not tell jokes. She has repeatedly admitted she just isn't specially good at it, that she doesn't think in terms of the familiar premise, set-up and punch-line. In fact, she has no respect for the usual, comforting and hackneyed comic assumptions most audiences expect to share with established performers and from which jokes, as such, are traditionally made. Instead, she exposes the fundamental dishonesty inherent in the assumption of commonality between a traditional stand-up comic and his audience, refusing to affect an indifference to money, or celebrity, tell pat airport, or mother-in-law, or political headline jokes, and talk about the difficulties or raising kids, or paying a mortgage. She doesn't much like kids. What she finds fascinating are celebrity, particularly of the kind arising from no discernible talent, tabloid fame, the power of hypocrisy, and the hypocrisy of power, otherwise unexamined privilege, and all the absurdities of success as defined in contemporary America, specifically as pursued in the epicenter of crap culture, Hollywood. It is her own life, then, as an insatiably ambitious, frustratingly unappreciated working performer, and a would-be star, in a thoroughly ridiculous system, that she talks about. Hers then not so much an angry rejection of the customary form of stand-up comedy, or the dominant culture-- no dreary post-modern rants, or overtly political tantrums --but rather a slyly indirect attack on all the underlying assumptions that both make that world of celebrity so irresistibly attractive, and hilariously awful. It is in her seeming failure to appreciate that honesty is the very last thing likely to win her friends and influence in such a setting that lends a genuine bathos to her humor. He apparent incapacity to abide by the simplest, if obviously insane, rules for guesting on talk shows, or performing for the military, or addressing her supposed betters at say, a charity auction, consistently undermines any and all her chances at becoming what she affects to worship, even as she trashes the pomposity and pretensions of every millionaire nonentity, self appointed authority and half-assed hack she encounters, usually by crashing the party. Ignoring any social restraint, verbal, institutional, sometimes even legal, gendered and otherwise, she is constantly pushing her way in, insisting she wants nothing more than to learn from experience, prove herself worthy, achieve a like share, and then, brilliantly, she reports her experience, to her audience -- exactly. The result is devastating caricature of both fan and famous. With delicious irony, it is in just such inversions of traditional proprieties, in making a career of telling tales out of turn, that Kathy Griffin has finally achieved some measure of the commercial and artistic success for which she has worked so hard, so long.

My favorite moments in her television show are, for such a consummate pro, the rare ones when she is flat happy. The camera can not always be played to, even by her, when it is ever present. It is when she laughs that she relaxes and is least likely to insist on including the viewer in every experience. Such moments are wonderfully revealing, and genuinely touching, filled as they are with an unexpected vulnerability. This more obviously has happened when the one has been allowed to share in her sadness, at the end of her marriage, or most movingly, in the death of her beloved, and very funny father, her viewers having been privileged to get to know her lovely parents as a regular part of the program. But seeing the comic made to laugh, by a friend, by her mother's endearing failure to always play along, or at some fresh absurdity from a passing stranger in a hotel lobby, is to glimpse the performer as just another human being, caught uncharacteristically a little off guard at the silliness of the species.

In her new memoir, Griffin makes another interesting choice, allowing herself a new honesty, one not aimed exclusively at amusing us. The book is funny as Hell, but she also allows herself some undisguised bitterness at some of the hurts and disappointments in her life. And her anger, otherwise always used to amuse, is occasionally expressed in her book without any apology, though directed as always at entirely appropriate targets: a truly reprehensible older brother with whom she refused any contact as an adult, the husband who failed their marriage and stole her money, and the many people, usually men, who underestimated and or condescended to her as a woman.

That's what I don't get about some of my women friends not appreciating Kathy Griffin. Even if one doesn't care to pay much attention to the objects of her satire, the television and tabloid personalities, the passing parade of instant celebrity, and even if her assumption of a wonderfully jarring, traditionally masculine kind of vulgarity and comic aggression, her straight girl camp, does not tickle others as it does me, I should think any woman might at least concede that, if not of my opinion that there is no funnier, more subtle and subversive comic, male or female, on the national stage right now, there is certainly better or more devastatingly effective feminist.

Give a bitch her due. All I'm sayin'.

No comments:

Post a Comment