Remember the old Platonic cave? The shadows danced on the wall, suggesting more then they showed, of a world not quite accessible. So it was with Broadway when one was a wee bumpkin boy, imagining whole shows from original cast recordings and the pictures on the album sleeve. If not every song made sense without seeing the actual show, and if sometimes the grainy production snaps failed to explain the sudden chorus of taps, etc., those records were none the less magical instruments, touchstones, the sometimes roughly communicated quintessence of another life, where romance happened "in two," sadness could be belted out and overcome, joy choreographed, lit beautifully, shared and heartily endorsed by applause. I never imagined myself a star -- couldn't dance and couldn't sing much once my voice broke -- but I could see myself seeing and hearing all of that glorious fun someday in New York City. I longed at least for the secondhand. And I knew the shows I knew as well as I knew my name. Still do, some of them.

Remember the old Platonic cave? The shadows danced on the wall, suggesting more then they showed, of a world not quite accessible. So it was with Broadway when one was a wee bumpkin boy, imagining whole shows from original cast recordings and the pictures on the album sleeve. If not every song made sense without seeing the actual show, and if sometimes the grainy production snaps failed to explain the sudden chorus of taps, etc., those records were none the less magical instruments, touchstones, the sometimes roughly communicated quintessence of another life, where romance happened "in two," sadness could be belted out and overcome, joy choreographed, lit beautifully, shared and heartily endorsed by applause. I never imagined myself a star -- couldn't dance and couldn't sing much once my voice broke -- but I could see myself seeing and hearing all of that glorious fun someday in New York City. I longed at least for the secondhand. And I knew the shows I knew as well as I knew my name. Still do, some of them.Because I never made it to see some of those shows, never made it to NYC but as a tourist, because some of the shows I came to know so well were long gone even as I imagined them, I grew up with a weird loyalty to productions and performers I'd never seen, or seen only in rare television appearances, but listened to a thousand times. For me, no one but Mary Martin would ever look authentic in that over-sized sailor's suit. No one but Alfred Drake understood "Fate." No one but Richard Kiley ever climbed that drawbridge into the light and immortality. And nobody is Mama Rose but Merman.

Now, if any of that is mystifying, or if any of the names are unfamiliar to you, I'm sorry, but it would take too long to explain. Drop by sometime, and I'll play you the records. Other than Richard Kiley in about his last revival, I never saw any of these people anyway, so I'm hardly an expert. That's rather the point. The performances that may have meant the most to me, I never saw, only heard. In every one of the musicals mentioned above, I eventually saw other performers, some quite good, some maybe even better than the originals, but none could or can even now displace the voices I heard first.

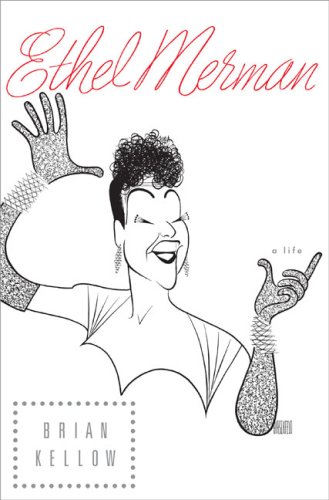

The Bargain Books table at the bookstore continues to be a source of siren song; with all the books I ought to be reading, I find myself listing as I pass, drawn inexorably to a Hirschfeld caricature on a white dustjacket, and my plans smash again, my direction undone, my duty abandoned. I can't quite remember what memoir in snowshoes I meant to start tonight, or what academic disquisition on salmon I'm meant to be reading. Any interest in the Northwest is lost to me just now. My committee work requires I buckle down and get to that teetering stack of mossy locals sooner rather than later, but tonight, I spent instead with Ethel.

Brian Kellow had an almost impossible task when he took up with Merman. How to communicate the wonder of that voice on the page? Now, Kellow writes regularly about opera, is roughly my age, and so probably never saw Merman in "Gypsy" either, so if anyone has the vocabulary for communicating the strange glory of The Voice in just words, this is the guy. I get him. He gets Merman. The author successfully recreates all that was most wonderful about Merman on stage as best as can be done now, now that she's long gone, for those of us never so lucky as to have seen her in, say, "Anything Goes," using judicious quotes from original reviews, the published reminiscences of costars and critics and fans, and much other solid research. His enthusiasm is genuine and familiar. He's a fan himself. He is happiest, and most articulate, describing the dance of those shadows. Of course, we have The Voice on record, for much of this, but Kellow's book fills in all the background, names the players, recreates the productions and makes everything better by so doing. He can only do so much at this late date, but he does it remarkably well. He gets The Voice.

Worse though for the biographer, as it turns out, than trying to bottle that lightning, was finding much of anything else inside. Ethel Merman: A Life, is the title Kellow used, and in it's blunt simplicity, it says more about the dame than anything longer might have. Ethel lived. That voice, Husbands, lovers, hit shows, disappointing kids, loving parents, she had. But an interior life? Not so much. Ethel didn't read much, even music, and she didn't think much, even about the roles she played. Ethel just was, like the sun. Kellow then can't do much with her private life but describe the blaze. Ethel scorched more often than she warmed. Such a phenomenon is perhaps best studied at a safe distance.

Doesn't matter now. Whatever Miss Merman was or wasn't as a person, as a performer, she was all that, a bottle of beer and a bag of chips. Brian Kellow, like any kid who listened, as I'm convinced he did, over and again, to "I Got Lost in His Arms," and the like, knows better than to question the magic. I've got Merman's "Gypsy" on right now. As Kellow might be to polite to say himself -- though Ethel would have without a thought -- fuck the rest.

Sing out, Baby!

I wonder if we saw the same production of "Man of La Mancha" with Kiley. It was in Pittsburgh, sometime in the 1970s. Must have been the year my father decided to give us "experiences" instead of Christmas gifts. I think I enjoyed it, though I can't say I've ever had much interest in American musical theater.

ReplyDeleteI wept like a crazy person at the end. And yes, I bet it was the same bus & truck. Kiley was on some TV show then, so during his summer break, he took the war-horse out for another run. I thought it was thrilling.

ReplyDelete