There are literary forms that pass, if not entirely out of use, then into something only vaguely recognizable, but still possible, as such. For example, think of the riposte, as perfected by Rostand's Cyrano, and now a feature of many a Rap duet, or of the epitaph, once among the highest compliments one poet could pay another, and now practiced, almost exclusively, as a regular segment, with appropriate quotation, by Larry King and the nightly entertainment reviews on television. The narrative, or story poem, among the oldest forms certainly, and continuously popular down almost to our own day, would seem to have all but disappeared from the English speaking culture, though I think a case could still be made for it's survival in the Country Western Song.

There are literary forms that pass, if not entirely out of use, then into something only vaguely recognizable, but still possible, as such. For example, think of the riposte, as perfected by Rostand's Cyrano, and now a feature of many a Rap duet, or of the epitaph, once among the highest compliments one poet could pay another, and now practiced, almost exclusively, as a regular segment, with appropriate quotation, by Larry King and the nightly entertainment reviews on television. The narrative, or story poem, among the oldest forms certainly, and continuously popular down almost to our own day, would seem to have all but disappeared from the English speaking culture, though I think a case could still be made for it's survival in the Country Western Song.When I was but a little bumpkin in the cultural outback of these United States, there was still a tradition of amateur entertainments, usually performed for civic and fraternal organizations and usually undertaken to commemorate some national holiday, like the 4th of July, or Lincoln's Birthday -- as we still called it then -- or to mark the coming of Christmas, in a setting not wholly, or exclusively consecrated to Christian piety, like the Scouts, or the Kiwanas Club, or in my case, The Grange. For any not acquainted with that last, The Grange, in rural America, was once a quite powerful and popular organization, organized after the Civil War, as a fraternal fellowship, and lobby, for the farmers, their families and dependents. By the time I came into The Grange, it's membership and influence had already waned, and there was, even then, already something almost painfully quaint in it's secret ritual, props and officers and rather threadbare pomps. I loved it, dearly. Every Grange Hall then, besides a meeting hall, a kitchen and space for pancake suppers and the like, had a small stage. This had a use in some of the more elaborate tableau in which the ritual delighted, but those little stages were also, for many a country boy and girl, the first experience of theatrical performance. Pageants, contests, raffles, skits and sing-songs were regularly staged on those narrow boards, and recitations still featured as a recognized and expected form of entertainment there. Besides such sacred texts of American history as the Preamble to the Constitution, The Gettysburg Address, and Washington's Farewell to the Troupes, the poetry of James Whitcomb Riley, John Greenleaf Whittier, Stephen Vincent Benet, Eugene Field, and Ella Wheeler Wilcox, all had regular airings there. If most of the names of those poets have gone to dust, it is because they wrote, often as not, the kind of poetry meant to be heard aloud, poetry for occasion rather than solitary reading, poems of patriotism and civic pride, historical poems, public poems, story poems.

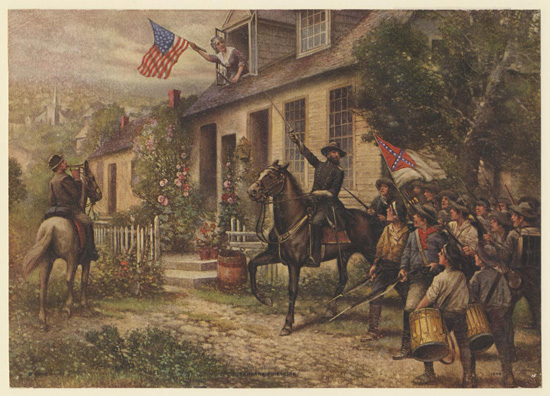

I myself received some of my first and most treasured applause for a recitation of Whittier's "Barbara Frietchie," which I can still do most of, without reference to the text, to this very day.

"Up from the meadows rich with corn,

Clear in the cool September morn..."

I am proud to say that I am far from being the most notable performer of this poem in the last century. In a recent joint biography of FDR and Churchill, I was thrilled to find a surprising anecdote of the two great leaders. Out for drive and coming to the town of Frederick, Maryland, Roosevelt started the poem from memory, and Churchill finished it likewise, every verse!

Barbara Frietchie was a real woman. At age ninety-five, she stood in the street in Frederick, and waved the American flag to block, or at least shame, the advance of Stonewall Jackson's rebel army. Whittier took some liberty with the facts, but captured indelibly the spirit of the woman, the moment, and added a benediction, typical of the poet, in two lines, near the end of the poem:

"Honor to her! and let a tear

Fall, for her sake, on Stonewall's bier."

The rhetoric and cadence of that poem has long since learnt the poem to a number of devastating parodies. And it would now perhaps be difficult to find an audience that would be moved to such easy tears as once were shed over it. I myself can not read it aloud, still, without a misty quaver, but perhaps that has as much to do with the memory of my beaming proud Grandmother Craft, watching me perform it on the little stage of the London Village Grange Hall, as it does with the memory of Barbara Frietchie. No matter.

On my most recent trip to Portland, on my final, quick pass through Powell's before I drove home, I had thirty dollars worth of store-credit yet to spend and was determined to leave only after I had exhausted it completely. I gathered up a few inexpensive books I'd passed over the night before, and made one last tour of the poetry section. In the anthologies, I noticed a thick, dark spine and pulled the book out, to read the title better. Best Loved Story Poems, selected by the unfortunately named Walter E. Thwing, and published, in 1941, by Garden City Publishing Co., Inc., I saw that book, editor and publisher were all long since relegated to history. At only five bucks, and in fine shape, the old book was added to my purchase without a second thought.

Struck for the second time in less than a month by a pernicious and violent influenza, I've spent my second sleepless night in a row, huddled pitifully in my favorite, ragged armchair, reading from this old book. Other old friends from childhood, like Longfellow's "Evangeline," Scott's "Lochinvar," and "The Highwayman" of Alfred Noyes have kept me company, but in these pages I have found many other stories and incidents, histories unknown to me, like Tennyson's "The Defense of Lucknow," and places into which I might never otherwise have ventured, like Wordsworth's "Hart-Leap Well." Reading out these poems, in even my sick, cold croak, has kept me warm, and entertained more hours now than I anticipated. If not every poem herein deserves to be better known, and if not every poet, even among the greatest included here, might wish his or her reputation to rest on just these tales and sermons, I don't think it matters much now. When was the last time anyone read out John Townsend Trowbridge's "Widow Brown's Christmas," as I did, with considerable pleasure, tonight?

If these stories and poems have lost their power to entertain a wider audience, it seems that for one reader at least, just tonight, there's nothing quite the equal for passing an uncomfortable and heavy hour, as might be had in the old fat book of story poems, "selected by Walter E. Thwing," now of blessed memory.

"The little toy dog is covered with dust,

But sturdy and staunch he stands..."

No comments:

Post a Comment