So. The first of our two Employee Shopping Days, as I may have mentioned, is nigh. Our discount goes up by ten percent, just for the day. There is much hoarding of books in the days and weeks before this. Many a used book that has been hunted and lost will turn out to have been squirrelled away, who knows how long ago, on the employees' hold shelves, only to re-emerge on our sales report's com Saturday morning. Others, particularly expensive sets and rare editions, will be thought better of at the last moment and come drifting back onto the sales floor, just in time to be counted in our inventory. This can be annoying, of course, but a blind eye must be turned. I myself am in no position to judge. Like both my work-spouses, I have my own cache of ill-considered treasures to review for purchase come Friday.

For instance, the greatest of Dickens' many biographers, was, evidently, something of an expert on satire, and made a wonderful anthology: A Treasury of Satire: Including the world's greatest satirists, comic and tragic, from antiquity to the present time. Selected and edited, with critical and historical backgrounds, and an introduction on the nature and value of satire, by Edgar Johnson. I include the whole subtitle as shown on the cover, by way of explanation. For me, having had Johnson's great two volume biography of Dickens recommended to me when I was doing research for the public readings of Dickens I did last year, and having read same with pleasure and respect, seeing his name on another book, whatever the subject, has sold me. The book was published in 1945, when George Bernard Shaw was still very much alive, and cranky, and Johnson's essay on just why Shaw belonged in the anthology, and why Shaw would not allow any of his work to be included, is reason enough for me to own the book. Into the yes pile then with Edgar Johnson.

We get beautiful unread hardcover books from local reviewers -- called, in the trade, "full copy" as opposed to advanced reading copies printed cheaply in paper covers -- and these are specially difficult to resist at any time of the year, but never more so than when one is already anticipating an even deeper discount and a lower price. Among the books that I am determined to buy this time, there are at least three or four novels of just this provenance. None are books I might not just as easily read by way of borrowing, and yet I want, inexplicably, to own them outright. That I will, in all probability, end up selling all these books on later, doesn't mean I won't want to buy them Friday. They are so shiny new, you see, so very much of the moment, subject to wide and flattering review, that I can't help but think, at least while I read them, that having my own copy will be the best. This is idiotic. Adding books like Elinor Lipman's The Family Man to my stack adds considerably to the expense of the day without adding much to my library, where it is unlikely to stay. But I want it. I can buy it. I will.

Other books are already being discarded as unnecessary. These, sadly, are for the most part remainders and discounted books I could more easily afford, even were my discount to be as it usually is. Somehow, it is easier to part with these than with new books I need only wait a year or less to see reduced to the same condition, on the bargain tables, when, their moment gone, they are returned to their publishers en masse by the chain stores and discounters, and sold to us as remainders, same as these others. Such is the fate of nearly all hardcover fiction and history nowadays, and one need no longer even be all that patient to wait. But those black marks on the bottom edges of remainders do make books less valuable, less desirable, and while these disfigurations are only meant to prevent the return of these books to their publishers at full value, in fact, they make books less attractive, even on a day of special discounts. Putting ten remainders out of my pile and back into stock allows me to feel, I suppose, like a judicious buyer, even as the price of my total purchase continues to climb. I can't help but think that I've built myself a straw man to just this purpose by piling so many remainders up behind the desk for Friday. I need hardly say that I will probably buy them all thereafter anyway.

Some stray little books, most of them used and already cheap enough and far from necessary, books like Elizabeth's Eccentrics: Brief Lives of English Eccentrics, Exploiters, Rogues & Failures, 1580 - 1660, by Arthur Freeman, will go to the cash register with me come Friday as much from my embarrassment at having held on to them so long rather than having sent them to the floor as I ought to have done. I will read these, or at least read in them, once I get them home, not so much because I still feel the same curiosity I did when they first came across the buying desk, but because I feel I ought to justify even so small an expense by finding something in them as good or better than the fist taste I took when I took each with me on a break or to lunch, no matter how long ago that might have been or how little I remember now of the little I read then.

I know how mad this all must sound to anyone not afflicted with bibliophilia. That I should end my week hauling home books I may not even remember my reasons for wanting does seem an irrational admission, now I come to make it here. But however irrational the impulse to buy, buy, buy, I do not think, when compared to almost any other indulgence available to the likes of me, that this extravagance rates even so much disapprobation as I might indulge here. The books I buy do not get eaten, or smoked, or lost, they continue life in or out of my possession. My books will survive me.

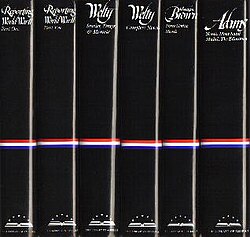

I even know, sorta, where some of them will probably go. Friday I will buy the four latest Library of America volumes. These, along with every other volume in the series purchased to date, are in my will. I'll have little enough otherwise to leave behind me. No bad inheritance, that; the whole long history of literature in America, preserved, collected and bequeathed. Will anyone really want my old car? my clothes? my ashes? My books though, I'm confident, will find readers after me.

There are worse vices than buying books, no?

No comments:

Post a Comment