"Essay: A loose sally of the mind; an irregular indigested piece; not a regular and orderly composition." From Samuel Johnson's Dictionary of the English Language.

"Essay: A loose sally of the mind; an irregular indigested piece; not a regular and orderly composition." From Samuel Johnson's Dictionary of the English Language.Reading Addison, or Lamb, or even, as I did today, a bit of Dr. Johnson's Lives of the English Poets, I despair, at least a little, of ever producing anything here that would entertain some reader as yet unborn. While I hasten to say that I am not much motivated, here or in life, by thoughts of posterity, I will admit that I do hope at least to entertain such of my friends as are still breathing. The examples of great writing by the English and American essayists with the strongest claim to immortality may not be the standard against which so trifling a thing as a daily blog entry are meant to be judged, and I do not presume to imagine that mine conform to either the hallowed traditions of the essay form, or to the happier examples of writing for the Internet that I regularly read myself, but I do wonder, in style, if I might not be doing my few readers a disservice in writing here the way I do. I mean to say, just look at that last sentence! Like most amateurs, I am too easily influenced and can not help myself, it seems, from adopting the faults of my betters while reproducing few if any of their virtues. And to what end? If anything I'm doing should happen to survive me, what will the child reader of some future century make of it? And much more to the point, why would even a contemporary read it when there are so many better things, truly superior, entertaining and enlightened things, already too little read but certainly sure of the future?

Yes, this is the usual whine of the unknown, the excuse for not doing most often put forward by the timid, and yes, I've used it often enough before now myself. But thinking again tonight about this little niche I've settled in, I think I may have earned it, not by my efforts to date, such as they've been, but simply by the regular repetition of the names and titles of those writers I read and love.

A friend sent me an email just today and shared with me a poem he'd heard in a podcast. The poem spoke directly, even eerily, to a loss he suffered years ago and from which he is unlikely to ever truly recover. That my friend should happen to listen on his computer to a stranger's voice reciting a poem by Charlotte Mew, and that that poem should speak so directly to his loss, is a proof of the true wonder of our times, of the continuing power of literature, and of the necessity of keeping our own eccentricities of preference as readers not to just ourselves, but sharing them by whatever means we may. The connections that allow a poem to find a new listener are the same now as they were when Charlotte Mews sat down to write the poem she did. The means of connection have expanded. The need of it has not changed since humans first drew a hunt on a cave wall.

That then I think is what I'm meant to be doing, in however small a way here, beyond whatever pleasure my doing so may afford me and or my few friends. That is what the Internet may do better by books than I can do just as a bookseller, though the outcome comes to much the same. If I can not actually put Dr. Johnson's brief biographies into the hands of my customers at the bookstore, first because I may not be able to get them to sell, and then, to be honest, because it is no easy thing to persuade some stranger to read such a book, I can at least express my enthusiasm for Johnson here. And if, as seems likely, Johnson himself, or any future readers of Johnson, would wonder that anyone should read so clumsy a thing as this blog and think this by any definition, even that of Johnson's own Dictionary, a proper essay, does not signify. I have, yet again, written Samuel Johnson's name and sent it out into the ether. I have conducted a modest sort of seance and called up his ghost, however briefly and presumptuously, that it may speak again across time and possibly to a reader neither I nor he might ever otherwise meet. Just as a minor English poet, long dead, has found the means to touch my friend straight to his heart just because some other Internet eccentric read her poem aloud, so too I might just tonight have lead someone unknown to me to read Johnson's "Life of Richard Savage." Who knows? It is possible.

Here then, a link to that work online, and for just a taste, the second paragraph from that work:

"That affluence and power, advantages extrinsick and adventitious, and therefore easily separable from those by whom they are possessed, should very often flatter the mind with expectations of felicity which they cannot give, raises no astonishment: but it seems rational to hope that intellectual greatness should produce better effects; that minds qualified for great attainments should first endeavour their own benefit; and that they who are most able to teach others the way to happiness should with most certainty follow it themselves."

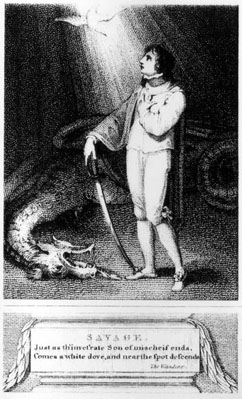

And another, to Savage's poem, "The Bastard."

And finally, another to the poem by Charlotte Mew that so spoke to my friend, "A Quoi Bon Dire."

No comments:

Post a Comment