Ease is a virtue too little appreciated in this, our hectic age, specially in literature. It isn't just that it has traditionally required money, "an income" as it used to be called, though that would certainly be of aid, as would the resulting leisure presumably requisite for writing little but exquisitely. Money, at least to those who have it rather than make it an avocation, is, as I understand it, "vulgar," much more so than sex, and seldom is explicitly referenced in the writing of those Cyril Connolly famously dubbed the "Mandarin" rather than "vernacular" stylists. Education likewise is worn lightly. (The reason, for example, George Steiner is not easy, is not because he has read so much, but because he wears his reading like Marley's chains and cash-boxes, making rattling and weighty even his lightest gesture.) Ease assumes not money or leisure or degrees, but sophistication. Not a New World value, that. We assess rather than appreciate, judge rather than consider, rank experience as Catholics sin; as material, or mortal, or venal etc. The closest we've come in America is "cool," which isn't actually all that like, as even at its easiest it is higher than it is wise; more doped than degage. Ease requires an apparent absence of effort, a certain sangfroid, hard to define in literary terms, at least without resorting to French, but the reader, or this reader anyway, may enjoy it, not without envy, but enjoy it all the same as it is never condescending or snobbish, isn't bitchy or mean, only apt. Ease never presumes too much, but is rather only too glad of the chance to introduce the unfamiliar, as friend might, to the best advantage for both. Ease, at it's best, is both gentle and right.

Ease is a virtue too little appreciated in this, our hectic age, specially in literature. It isn't just that it has traditionally required money, "an income" as it used to be called, though that would certainly be of aid, as would the resulting leisure presumably requisite for writing little but exquisitely. Money, at least to those who have it rather than make it an avocation, is, as I understand it, "vulgar," much more so than sex, and seldom is explicitly referenced in the writing of those Cyril Connolly famously dubbed the "Mandarin" rather than "vernacular" stylists. Education likewise is worn lightly. (The reason, for example, George Steiner is not easy, is not because he has read so much, but because he wears his reading like Marley's chains and cash-boxes, making rattling and weighty even his lightest gesture.) Ease assumes not money or leisure or degrees, but sophistication. Not a New World value, that. We assess rather than appreciate, judge rather than consider, rank experience as Catholics sin; as material, or mortal, or venal etc. The closest we've come in America is "cool," which isn't actually all that like, as even at its easiest it is higher than it is wise; more doped than degage. Ease requires an apparent absence of effort, a certain sangfroid, hard to define in literary terms, at least without resorting to French, but the reader, or this reader anyway, may enjoy it, not without envy, but enjoy it all the same as it is never condescending or snobbish, isn't bitchy or mean, only apt. Ease never presumes too much, but is rather only too glad of the chance to introduce the unfamiliar, as friend might, to the best advantage for both. Ease, at it's best, is both gentle and right.Ease need not always be nice, however. The writer who has it needn't like everything considered good, but the critic with ease may dismiss without degrading, accomplishing more with a shrug, dismissing as dull what is inferior, than might be done otherwise with the bloodier tools with which more common critics hack. But really, criticism all but ceases to be such when it is done with ease. The essay, being personal and discursive, is the most natural literature for its expression. (That the essay was the invention of aristocrats is no coincidence -- who else had the time?) And if aristocratic in origin, so ease tends to be a virtue still more of the right than the left. Ease assumes stability, and if not a disinterest in politics, then at least a disinterest in action. The left, even come briefly to power, can never quite afford to sit so comfortably on its ass and observe. No revolution was ever casual. To fight, one needs more than aesthetics as philosophy, not just a sharp tongue, but sharp teeth. Parody requires ease. Satire needs savagery.

That is what makes ease so uncongenial to the times. Even conservatives, at least in their present American incarnation, are disinclined to be openly disinterested. Rather than admit they do not care much for children, or the poor, they will nowadays change the subject and quaintly rave about unwed mothers, immigration and "the gays." But then, as I said, Americans have never had a proper aristocracy. For us, the only privilege of wealth is power. Sophistication comes of distraction, an eye not kept on the main chance, and suggests, to real capitalists, decline. (Jesus Christ forbid the kleptocrats notice any art but architecture, which is too big to miss, or we'd have ballets the size of the Chinese Olympics opening ceremonies, murals of Paul Allen on the outside of Frank Gehry's already hideous building, and the Colossus of Rhodes, rebuilt but with Donald Trump's hair, bestriding the Hudson River.)

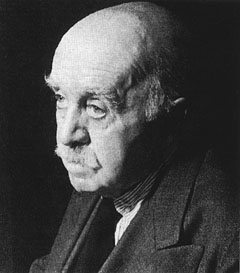

Ease, as I've suggested, is easiest in French, I assume, as they seem to have so many good words, adopted by the English, to express its variety. But I can not read French. So I tend to take my ease, if not in translation, then with the English. Beginning a vacation -- or better say a suspension of work, as I'm not leaving the house this week -- I have need of ease. As my theme this month seems to be poetry, and as I've been interested just now in poetry from writers not know specially as poets, I take from my shelf of favorites, The Incomparable Max. So G.B.S. named him. I possess two volumes of Max Beerbom's poetry, Max in Verse: Rhymes and Parodies, and a later edition, Max Beerbohm: Collected Verse, from the same editor. Beerbohm was England's preeminent caricaturist, one of her greatest essayists, a perfect parodist, the master of all minor forms, including, as it turns out, the occasional poem, scribbled in guest-books, or left as a note on a breakfast table, or inscribed in a book. If he never meant any but his lengthier parodies, of Hardy's The Dynasts, for instance, to be published, I don't think Max would have minded, had he lived to see his "Collected Verse." The title would have delighted him. His first published book was titled The Works of Max Beerbohm.

As ever with Beerbohm, there are many delightful little things in these books, though, as with much he did that was not intended for publication, it behooves the reader to have at least a passing acquaintance with the prominent figures and fashions of Max's day, and to remember, as he would have been the first to point out, Max Beerbohm lived well past the day in question. How else appreciate this clerihew about the late, great lady novelist, now all but forgotten?

MRS. HUMPHREY WARD

Hic jacet Mary Augusta Ward,

A mighty writer before the Lord.

Apotheosis is hardly a gain

For one who moved on so high a plain.

But he does embody, even in his slightest efforts, the ease I've been on about above. There's been no one to match him for it since. Witness this critical, even Philistine shrug, and imagine anyone less amusing making it without sounding silly:

ON PROUST

Dear Esther S. ---- I'm in distress,

It's very sad! My taste is bad.

The men that boost the work of Proust

(Those scholars and those Gentlemen,

Those erudite and splendid men,

Of whom the chief is Scott Moncrieff)

All leave me cold. Perhaps I'm old?

'The reason why, I cannot tell,

I do not like thee, Doctor Fell...'

But why not like the late Marcel?

Perhaps he wrote not very well?

This, bien entendu, cannot be

He was the Prince of Paragons

(As undergraduates all agree --

Or did in nineteen-twenty-three --

With full concurrence of the Dons).

Are now, as ever, geese to me.

Pity the blindness of poor M. B.!

P.S. How sad that I'm alive!

October Nineteen-twenty-five.

Max Beerbohm is my favorite English writer and had I the space here, I would post whole essays (of his) to justify my appreciation. I will always envy him his ease, and be grateful for his example. Would that my touch were half so light, my best so good as his least effort. But even just a bit of Max is better than a considerable load of me, or almost anyone else. So, one last example then, the last know poem of Sir Max Beerbohm, by then quite old, and very near the quiet end of his long and largely happy life, but still very much at his ease, at least so far as his pen:

VALEDICTORY

Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him well --

A fellow of infinite jest.

Where is he gone to? You never can tell.

Let's anyhow hope for the best.

No comments:

Post a Comment