A good friend is writing a critical study of enthusiasm. While the enthusiast was once understood to be one possessed or inspired by god, and not in a flattering way, what interests my friend is not divine inspiration, but the eye for it in others, not the God but the devotee, not the Poet but the amanuensis; the lovers, translators, promoters and pimps for Genius. Knowing my affection for the minor, and my reading of biography, particularly literary and specially English, the critic asked me to suggest examples. Very flattering. One of the most obvious, not already on his list, was Dorothy Wordsworth.

A good friend is writing a critical study of enthusiasm. While the enthusiast was once understood to be one possessed or inspired by god, and not in a flattering way, what interests my friend is not divine inspiration, but the eye for it in others, not the God but the devotee, not the Poet but the amanuensis; the lovers, translators, promoters and pimps for Genius. Knowing my affection for the minor, and my reading of biography, particularly literary and specially English, the critic asked me to suggest examples. Very flattering. One of the most obvious, not already on his list, was Dorothy Wordsworth.Any reader of the poet has met his sister. In addition to her contributions to and appearances in his own writing, their letters and the memoirs and letters of their whole circle of friends and admirers, Dorothy Wordsworth's life, inseparable from that of her brother, has been told time and again. We would not have had William without Dorothy. There was an exhaustive biography of the lady herself published as recently as 1985. Miss Wordsworth's own journals, and it particular The Grasmere Journals, only published in 1954, have established her as a minor classic in her own right.

What sometimes seems to puzzle contemporary critics of the Wordsworths, and confused their contemporaries not at all, was that Dorothy remained the lifelong enthusiast, living with her brother, and eventually his dear wife, all her unmarried life, and seemingly satisfied with not being the Wordsworth meant when the name appears in the singular. That Coleridge and Hazlitt and De Quincey and the Lambs, that all the famous and not famous friends, admired the sister, even when they might have ceased to be friends with the poet, says a great deal for her. That she could love The Laureate no matter how dull he became, says more. (That he loved and respected her to the end of his days, in his biography, with his happy marriage, certainly makes the old man better than he would otherwise be remembered.) The Wordsworths lived together, loved and respected one another. He was the Genius. She the enthusiast. How shocking.

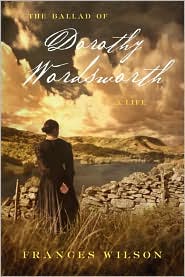

In a new critical biography, The Ballad of Dorothy Wordsworth: A life, by Frances Wilson, just published by Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, this marvel of enthusiasm is all but unrecognizable to anyone familiar with her from previous biographical considerations. Her latest biographer, not much interested in either the poet or the truth, from the first page, is off; "paraphrasing" poor Dorothy, rather than quoting, when it suits, speculating, inflating, teasing, and misquoting. Why?! Dorothy Wordsworth was a fascinating person. Her relationship with her brother, being all but her all, has been the subject of unending interest, and some of it unkind, even prurient. Never before though have I ever seen that relationship, or Miss Wordsworth herself, so bent, abused and willfully, stupidly made ridiculous, and in the service of what, exactly? If, in making the poet sound utterly unfeeling and or incestuous, one is meant to find the sister more sympathetic, then Ms. Wilson fails. If Wordsworth wasn't much of a brother, and less of a genius, then Dorothy wasn't a victim, she was a fool. There's no evidence of either characterization being true. And why write a biography of a fool? Is the reader of Ms. Wilson's book meant to be encouraged to read the Journals? If Dorothy's journals stand alone as art worthy of interest, as Ms. Wilson insists, then why ignore or refuse to appreciate the very qualities that make them charming: the avoidance of gossip, of personalities, of self involvement, the insistence on observation, on the beauty of the natural world, on looking out rather than in? Again, endless interpolation of a particularly mean and vulgar psychology, of dizzy rehearsals of what may or may not have been in the woman's mind when she wrote, when she so seldom and or simply tells us herself, doesn't add to the value of Dorothy Wordsworth's writing, it misses it entirely.

I do not understand the point of speculative biography, of writing not the life that was lived and known but the life vaguely and erroneously perceived as possible. I do not understand criticism, predicated on an analysis of what isn't present, but might be have been purposefully unsaid. However cleverly constructed, however seemingly detailed, if one is writing not "a life," but a life like, not opinion but persiflage, then the result is not biography or criticism, it's necrophilia.

So, having made a muddle of her journals and tabloid of her life, why then should her latest biographer have decided to write a "life" of Dorothy Wordsworth in the first place? Well, let's apply her own technique to the biographer. Knowing nothing more of the woman than the bit on the back jacket flap, and using her own standard for honesty, I can say definitively, Frances Wilson is...

But why stoop to her level, even here, just for fun? I myself am just enough of a gentleman to draw no further attention to her embarrassing penchant for what my sixth grade principal used to call, "unfortunate departures from the truth." Perhaps it would be best -- it certainly would be kinder to the memory of Dorothy Wordsworth -- to just look away. Say no more.

No comments:

Post a Comment