At eleven-thirty on Saturday night in those days there was Chiller Theater with "Chilly Billy" Cardille on Channel Eleven, Pittsburgh, PA. Before I was old enough to stay up late to watch horror movies, I would sometimes creep down the stairs and peer over the back of the sofa while my older brother watched House of Dracula, or The Man Monster, or Blood Sucking Monkeys from West Mifflin, etc. (In those days you watched what they ran.) Before I was really old enough to understand or appreciate the nuances of cultural exchange, the film that scared me the worst was a fleeting glimpse of a Mexican lucha libre movie in which it was not the bloody werewolf who terrified me, but rather the leading man; a hulking wrestler who wore a skintight mask that covered his whole head. Only his eyes and mouth suggested a man under the mask. He was powerful, violent, and hyper-masculine. What made him scary though was that absent face. Otherwise he dressed like a huge but rather natty car salesman; polished shoes, golf shirts, and tailored sharkskin suits. Nobody in the movie seemed to find this sartorial combination the least bit odd, let alone disturbing. I found it unsettling in ways I could not understand or explain; so many muscles, great, hairy hands, a featureless face, such sharp creases in his slacks. And yet the leading lady clearly found him attractive, mask and all, and nobody ever told him to take it off. No one seemed to notice it. When he lit a cigarette the smoke would curl out the corners of his mask. Scared the bejesus out o' me. When I was a little older, adults regularly asked me if all these monsters didn't give me nightmares. Well, sure. The only one I actually remember giving me more than one sleepless night though was that faceless wrestler in a custom suit.

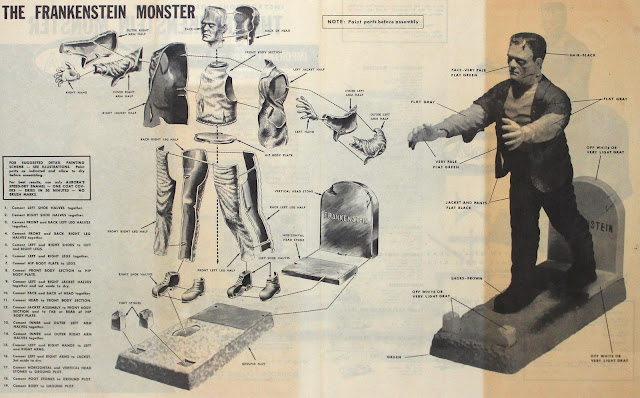

Television was all rather hit or miss in those days; three channels, four if the weather allowed, and other than Saturday nights, horror wasn't regularly featured in afternoon shows like The Million Dollar Movie. Many classic horror films I knew only by reputation. There were stars like Lon Chaney Sr. encountered only in film-stills and descriptions in the monster magazines. I had his Phantom of the Opera as a plastic model of course, and I studied the photographs of his make-ups the way other, more pious little boys might study the face of the Virgin in a Renaissance annunciation or St. Sebastian's (ahem) wounds. I learned facial anatomy by way of drawing Chaney's Phantom and his Quasimodo, the actor's face distorted by wires and putty. I drew monsters constantly, the ones I could see and the ones I invented. One of the few drawings to have survived from those long ago days is a fairly accomplished portrait of Karloff in his famous entrance from Frankenstein. (When my father died a few years ago I found this drawing and a number of others I'd done as a child, carefully preserved in a box in Dad's closet. I kept the Karloff.)

When I was a teenager in the later 1970s my interest in horror films waned as the genre devolved into mindless slashers with high body counts and featureless killers. I still went to those movies, everybody did, but I never loved them the way I'd loved my old black & white monsters. By then books -- including books about film -- had largely supplanted movie monsters as my primary obsession. Novels gave me monsters more complex than the staggering mummies and giant tarantulas of my childhood. Of course by then I'd read Poe, Mary Shelley and Bram Stoker, Sheridan Le Fanu, all those Hitchcock anthologies, The Monkey's Paw, Interview With a Vampire (four times in a row,) and the early Stephen King. At some point I came across Dalton Trumbo's antiwar novel of oppressive body horror, Johnny Got His Gun, and The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gillman, and Guy de Maupassant's The Diary of a Madman. I read William L. Shirer's The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, cover to cover. I began to appreciate that horror may actually have less to do with ancient curses and supernatural visitations and more to do with anxiety, violence, and ideology. Evil doesn't require a curse or chemicals in technicolor tubes and pipettes, or the substitution of good brains for bad. (And good can come from the defiance of God.) Not all monsters are made in interesting ways. Some monsters we make for ourselves, and or of.

Can't be a serious student of monsters for long and not know that the villain is not always the monster. Anyone may prove a villain. Anyone. Monsters are made.

Considering my age and established affection for old books, no one should be shocked to learn that I am not much of a fan of new words. The wonders of science and technology require an expansive vocabulary, and nonsense thrives on the scroobious and the runcible, but literature for adults gets largely by on what's already to hand. The answer to this is usually Shakespeare and sometime Joyce, with neither of whom am I prepared to argue. My discomfort* comes mostly from verbing, and words like "verbing," aka denominalization, and verbification, all of these words for rendering a noun into a verb, and all, please note, almost equally ugly. English does this easily enough, as it does most things other than spell. Most commonly you just add "ing'' and you're in, friend. I would still argue for "befriend," but I grow old, I grow old, and wear my trousers rolled. (No, honestly I do, 'cause I'm short.) It is not just the newness that makes me wince. "Hashtag" was already ugly to my ear, vaguely German, long before it was verbed (?). There is however one such word I am more than ready to endorse, though I doubt I will ever use it much myself. "Othering" seems to me an idea I needed back when my monsters came mostly in shades of gray and often had fangs. Had I that sense then, I might have understood a bit better my fellow-feeling for protagonists pursued by torch-bearing villagers. I will leave the queer theorizing to them what do it more easily than I, but indeed there was a little fairy at the bottom of our garden, Maud, and it was me -- in case you were missing this.

Later still when I took up reading not only literature and biography but literary biography, I was introduced to yet another category of loveable monsters -- the authors themselves. Not that there aren't absolutely admirable and very decent people who've written great work. No one really has a cross word to say about Washington Irving and so far as I could tell Charlotte Bronte never hurt a fly. Harmless isn't the same as happy of course. Think of poor John Clare. I still remember the deep and abiding shock of reading a prize winning biography of a prize winning novelist and realizing that the biographer had clearly come to loath his subject. I understand getting in too deep to pull out, but that book seemed cruel. Where was the sympathy for the monster so clearly misunderstood, for the scars and the pains that made him? I had a similar experience some years later when I read a good writer's devastating memoir of a great writer who had once been a friend. In the end neither seemed a very nice man. (It was an interesting book though.) More usual was finding that even favorites were flawed in ways not anticipated from reading their fiction. Dickens did not so much end his first marriage as -- metaphorically -- set his house afire with his poor wife in it. Dear Barbara Pym, the very definition of minor genius clothed in twin-set and pearls had a dalliance among the Nazis and organized a stalking party to trace her gay neighbors' comings and goings?! Heavens, Miss Pym! The diaries of Henry Louis Mencken, the letters of Philip Larkin, there would seem to be no end of ugly, posthumous revelation yet to be had among the surviving papers of the great. The only really monstrous aspect of most writers usually is ego and that's a small price to pay, at least retrospectively, to gain War and Peace or Les Miserables. Some writers seem to have been more than man-sized, their destruction clumsy and unintended, their monstrosity strangely glorious as their intentions were probably good, or at least in noble service of their art. Writers are made just like monsters by compulsions they may never and need not understand. Real writers, great monsters, are fascinating because they want nothing so much as to understand and to be like the rest of us though they aren't. What do most monsters want? To find love, be normal, or worse comes to worst, to be left alone to talk to their maker as they drift on an ice-flow. I certainly get that. Their struggles are ours writ large. Frankly, to me at least it seems easy enough to love Balzac and Jean Rhys and even Gore Vidal now they are all safely (un)dead and cannot die.

Of villains there is no end. The world right now is over-run. Literature? I'm glad to say that genuine and thorough shits like Louis-Ferdinand Celine and Philip Roth are reassuringly rare. Real villains cannot help but gloat and glower and justify themselves despite not having been asked. No more attractive on the page than in the last reel. Other than one's own, resentments are seldom interesting and bullies are always boring when they explain themselves. (That's it? That's how you justified that nasty shit you just did?! Pretty lame, son. Time to go.) Much as we may enjoy the villain, we wait to watch him go off the side of the building every Christmas and we cheer. But, oh my monsters! Monsters are different. Monsters don't die. Some of them can't even when they want to. Villains are selfish. Monsters are cornered. Monsters are compelled, confused, cursed, more than the sum of their badly stitched parts. One might envy a villain his lair or covet his toys, but ultimately we're glad of his failure. Monsters are sympathetic in a strange way even at their worst. Might be as simple as recognition -- there but for. We've all looked in the mirror and seen a monster -- and if you haven't, guess what? You're a villain. Unlike the villain's crimes, the havoc of monsters is made for us all.

Ours is not really a time for great monsters as who has the time for all that back-story? Times are complicated. The future is uncertain. We like our heroes simple again, alas, and our villains barely animated. It's boring. Most of our monsters now are just villains in rubber masks. The masks come off in the big reveal and we've all been Scooby Doo-ed again. Not a monster, just another bad guy, and if it hadn't been for those darned kids! One grows so very tired of those damned kids. But there are still monsters, ancient and modern, and more being made if you only know where to look. My monsters hide in dark corners, covered in dust, and smelling of the tomb. It seems they've been waiting. Some of my monsters are just where I left them, quiet now as Kong, if only for the time being. The ones I love best haunt old libraries and hide in old bookshops, but their descendants and progeny are not unknown anywhere in the wide world. There are always monsters I haven't met yet. Like still calls to like and I've only to listen. Hear them? They hector and howl and laugh at odd moments and talk to themselves, often in foreign accents. The children of the night, oh, etc. Their variety can be surprising even to those like myself who love them. To admire a monster one must try to understand its nature and yet one must be willing to accept it as it is. I do not support the idea that monsters make for bad art, or that bad art is always made by monsters. It's the villains you've got to keep an eye on. They always lie. It's rank villainy to deny our monsters, to make men with big muscles our heroes again, and then suggest they are somehow made unhappy in the exercise of their gross power. It's a villain who describes cruelty as common, sees the weak as risible and insists that unkindness is funnier than the fall of pomposity. Villains are selfish and see no sin in this. Monsters rage at the loss of love and long for humanity and death. Good taste and happy endings have their charms, I don't deny it. So do puppet shows and Saturday morning cartoons. But so does a rude Rabelaisian belch, a roaring story, loud women, old witches, so do blood, guts, anguish, and Beckett, and maybe a sustained maniacal laugh. It is personality makes the great monster, not the cleverness of a scheme or the elaboration of a plot or perfectly articulated reasons for past bad behavior. That's all villain shit. Large or small the best monsters are more than just badly behaved, they are us. Monsters belong to us as few characters can. No one loves Dickens for his heroes. Great monsters are never simple, anymore than we like to think ourselves. Monsters are better for being wrong and righteously indignant at their cruel fate, lost and twisted, and trapped, and tragic. Face it, monsters are inherently better than any dull binary of heroes and villains (-- and that, fan-boys, is why Guillermo del Toro deserves an Oscar and the Marvel Universe can suck it!)

Right now my monsters tend to behemoths. Weird in a way, as I've never really been a Kaiju guy. (As a youth I read a crushing essay by a science writer explaining patiently how gravity would defeat most giants and I never quite recovered.) Seems I like 'em big now. Whatever the dimensions and limitations of their authors, I am now in the business of reading big books at least in large part because they big. For the neglected little gems of world literature there will always be customers, and dealers. Happy to help you to a Nina Berberova. Have you read Jenny Diski? Has a working hour passed without my having mentioned Beerbohm and a whole day gone by without Brigid Brophy? How hard can it be to convince a reader of contemporary fiction to pick up a reissued novella or to try a funny essayist when I've been doing largely that for most of my working life? I've always like short books and slight things. I've always preferred the miniaturist to the muralist, the minor to the major, a jazz trio to a big brass band. I am myself a maker of little art. So why and from where this attraction to the monstrous again?

I need Samuel Johnson now. I need the monstrous profusion of his conversation and the loudness of his voice. I need, Sir, the rolling, sonorous wisdom of a big man of large experience and big, even brutal honesty, to stand surety against the villains. Heroes are all well and good so far as they go, and nobody is kicking Chris Hemsworth out of bed for eating saltine crackers, but I want monsters. I want a face and a soul with scars. I look around me for grotesques. I require exaggeration. The times seem to me to call for roaring. "Life is everywhere a state in which much is to be endured, and little to be enjoyed," he moaned. "The world, in its best state, is nothing more than a larger assembly of beings, combining to counterfeit happiness they do not feel, employing every art and contrivance to embellish life, and to hide their real condition from the eyes of one another," he howls and does us all rough justice. He is not always unhappy, despite his reputation, and he roars just as loud when he laughs And yet, "Human happiness has always its abatements; the brightest sunshine of success is not without a cloud." Monster. He is right now my giant and I enjoy that he eats hugely, rudely and crushes the petty and the pusillanimous underfoot. He stands astride London, and he stoops to pet his cat. He sits loudly down to a quiet tea with the blind, the halt, the maimed, and the broken. He is grave and yet defies gravity. How not to love such a monster?

I need big books now to weight the scales against the villains. Life and more life, and death too, friends and monsters. After Johnson's wife died he wrote, "I have ever since seemed to myself broken off from mankind; a kind of solitary wanderer in the wild of life, without any direction, or fixed point of view: a gloomy gazer on the world to which I have little relation. Yet I would endeavor, by the help of you and your brother, to supply the want of a closer union, by friendship: and hope to have long the pleasure of being, dear Sir, most affectionately yours..."

Every monster wants a friend. I am glad of my monsters.

"It is true we shall be monsters, cut off from all the world; but on that account we shall be more attached to one another."

-- Mary Shelly, Frankenstein

* Also? Dropped consonants. It's impor'ant, people, you know, like the in'ernet.