I confess, I'm guilty of being more than one bird here. Sorry, everybody.

"I hold any writer sufficiently justified who is himself in love with his theme." -- Henry James

Thursday, January 31, 2013

Daily Dose

Wednesday, January 30, 2013

A Caricature

I confess it. The beloved husband and I have become just the littlest bit obsessed with yet another reality show. Oh, the shame of it. First we saw the film. Then that spawned the TV show on MTV. Now we record every episode, usually pausing at least once to admire the boys, Nev & Max, in the invariable "wakin' up all toasty and tousled scene." It's all good from there.

Anyone who doesn't own a TV may still (?) be wondering what this "Catfish" phenomenon is, now that some famous football person's been in the headlines. Well, a catfish is now -- thanks to these boys and their movie -- one who pretends to be someone else in a relationship on social media, etc. Thus the poor footballer from Notre Dame who thought his imaginary girlfriend had died, and so on. This happened to Nev and his brother & Co. made a documentary about it. Now a television show.

It's bloody fascinating. The last episode? A stunningly beautiful soldier boy falls in love over the pixels with a male model from Florida. Guess how that's worked out? Well, you might be surprised.

I can't frankly imagine this lasting as the premise is dependent on both parties meeting for the first time in person via the MTV show, and, like Intervention before it, the day is doubtlessly coming when there won't be but one or two souls left on earth who aren't in on the premise. Until then though, we have a new guilty pleasure in our house, my beloved A. & I, and we're still planning dinner, laundry, reading and life around watching this thing.

Now if Max would just take his shirt off...

Anyone who doesn't own a TV may still (?) be wondering what this "Catfish" phenomenon is, now that some famous football person's been in the headlines. Well, a catfish is now -- thanks to these boys and their movie -- one who pretends to be someone else in a relationship on social media, etc. Thus the poor footballer from Notre Dame who thought his imaginary girlfriend had died, and so on. This happened to Nev and his brother & Co. made a documentary about it. Now a television show.

It's bloody fascinating. The last episode? A stunningly beautiful soldier boy falls in love over the pixels with a male model from Florida. Guess how that's worked out? Well, you might be surprised.

I can't frankly imagine this lasting as the premise is dependent on both parties meeting for the first time in person via the MTV show, and, like Intervention before it, the day is doubtlessly coming when there won't be but one or two souls left on earth who aren't in on the premise. Until then though, we have a new guilty pleasure in our house, my beloved A. & I, and we're still planning dinner, laundry, reading and life around watching this thing.

Now if Max would just take his shirt off...

Daily Dose

Tuesday, January 29, 2013

Daily Dose

From Religio Medici & Other Writings, by Sir Thomas Browne

OF OLD

"Of old Things we write something new, if Truth may receive addition, or Envy will allow any Thing new..."

From The Epistle Dedicatory, to The Garden of Cyrus

OF OLD

"Of old Things we write something new, if Truth may receive addition, or Envy will allow any Thing new..."

From The Epistle Dedicatory, to The Garden of Cyrus

Monday, January 28, 2013

Daily Dose

From Sir Thomas Browne: A Doctor's Life of Science & Faith, by Jeremiah Finch

From Sir Thomas Browne: A Doctor's Life of Science & Faith, by Jeremiah FinchNEVER

"I shall never be perswaded, that God hath shut up all the light of Learning within the Lanthorn of Aristotle's braines."

From Chapter 9, Enquiries into Vulgar and Common Errrors, a quote from Walter Raleigh's Preface to his Historie of the World

Sunday, January 27, 2013

Sting

Infinite Jest was one of the first answers. I never got past the second tennis match myself, so I get that. Jorie Graham? That was interesting. Couldn't decide if "she was up to something, or nothing." Clever. Gone Girl? "Just because of the subject matter." I blushed at The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, as I must admit I've never finished it myself. But there certainly were books that people had finished and found impossible none the less, with both The Unvanquished and The Sound and the Fury making that list, along with Crime and Punishment and The Brothers Karamazov, each from a different reader, interestingly. There were more.

The question was simply, "What was the hardest book you've read?"

Didn't want to be any more particular than that, though nearly everyone I asked asked me to be. A book they'd finished? A book they'd liked, or disliked? Not the point. What I wanted was not so much the titles as the explanations, and those were quite interesting, I thought. When I formulated the question, I hadn't even been thinking about contemporary fiction, for instance, or politics, or violence. I asked coworkers at the bookstore mostly, and a couple of social media friends. Hardly a scientific survey, but then not a very objective question.

Doesn't really need saying, but what's difficult is different, not just from book to book and reader to reader -- though I must say I smiled in recognition more often than not -- but from one experience of a particular book to the next, if there's been more than one. That was something of a happy surprise to me too; how many of us either have made or still intend to make another go at these books. Something in the nature of the serious reader, I suppose, and we all of us are that had the conversation, that even our worst experiences in reading weren't seen as having been wasted. But then, I've said that wrong, haven't I? No one said that what was hard was worst, not one. Moreover, nearly everyone assigned the difficulty not to the text but to reader, though all with some qualifications; to do with age and experience, or other commitments and distractions, and most often, simply time.

I found the whole discussion very reassuring.

I was prompted to this question by reading George Herbert. I'll get back to him, but to tell the thing in the right order, I should start not with him, but with my last vacation, back in October. Every year I go home to Pennsylvania to see the old people. Every year I use the trip as an excuse to buy used paperbacks, something I otherwise almost never do. I always take too many books, naturally. The ones I read in those two weeks, I leave behind, along with anything I might not have much liked. Roughly once a year then, I enjoy buying books I don't intend to keep: mystery novels, light comedies, neglected classics, at least one or two familiar things I mean to reread. It's all ridiculously ambitious and, as there are no consequences to failing, and it's such a negligible financial investment, it's all a bit of a fantasy, really. (Though I must say, I've actually been able to get a fair bit of reading done as my parents have aged and there's nobody much else to be entertained of an evening but ourselves. Early to bed with a book seems the perfect height of indulgence to me nowadays. I needn't even review any of my reading here afterwards, unless I've a mind to. Vacation, you see.)

This year, in addition to the Christies and the Kawabata I never got to and the Orwell essays I barely touched, and for reasons I can not explain, I also picked up the anthology pictured above. Not my period, you understand, The Seventeenth Century, at least, not before now. The book, edited by one Evert Mordecai Clark, was part of a series, and any of the three books after this, The Eighteenth Century, The Romantics, or The Victorians, had I come across one of those, would have been a much likelier choice. I know those last two specially well now, and have at least some experience of the earlier. But before that? Shakespeare, of course, and a bit of Jonson, and then? Mind the gap. I can only think, in the absence of something more familiar, I wanted some poetry, and this one, with both poetry and prose and at roughly six hundred pages, seemed to fit my impulse. Anyway, I bought it. Then I kept reading it.

And I've kept it, the paperback anthology, because it is that good. The early essayists were a revelation and favorites, naturally, from John Earle (1601 - 1665) to Thomas Fuller (1608 - 1661). For the most part, they are just this side of sermons but of such simplicity and good nature as to never feel the drag of preaching. In fact, all the prose of every description, from history to natural science and letters, all of it has a warmth and immediacy I would never have anticipated in what I can't help but think of as a very formal period. Lovely surprise.

It's the poets who dominate though, naturally enough in a book I actually selected for poetry. I was, if anything however, even more resistant to reading some of these for that same reason: piety. Well, I was right about that, but I was also a fool.

It was all to do with Milton, I should think. I never have taken to Milton. His "Paradise" has always been among my very hard books and I've never yet made it. In my mind, he stood not just well above his times, but for them, so I hadn't had much of a look around him before. Like the shadow of some magnificent, coldly intimidating cathedral cast across the whole of Stuart and Puritan England, was that great poem.

But I'd missed out on Robert Herrick ( 1591 - 1674.) He became something of a preoccupation after I got home from my trip. Twenty pages in this book of his Hesperides and we were old friends. I had to buy a proper Oxford edition, and read right through it. He has all the charm and good humor of what I can't help but think of as a slightly older, Tudor England, and nearly none of the Puritan in him. He's eminently likable, like Henry Vaughan (1622 - 1695); musical and no stranger to a good meal or a pretty girl, from the sound of him. For me now, they represent all I'd missed out on, thinking the 17th a century of black-clad churchmen.

But then, there's George Herbert, and George Herbert is hard. Herrick was a clergyman no less than Herbert, but Herbert is harder. Herbert is one of God's great poets, and I don't much care to read about God, specially Herbert's rather bloody-minded Christ. It seems Herbert was a very nice, devout and even dear sort of person, but far from even the unwitting sensualists one so often finds for instance among the Renaissance Saints. His is a very pure, rather strict observance, no less solemn in his way than Milton. Not my kind of fellow. And yet. I am now every evening with George Herbert.

But then, there's George Herbert, and George Herbert is hard. Herrick was a clergyman no less than Herbert, but Herbert is harder. Herbert is one of God's great poets, and I don't much care to read about God, specially Herbert's rather bloody-minded Christ. It seems Herbert was a very nice, devout and even dear sort of person, but far from even the unwitting sensualists one so often finds for instance among the Renaissance Saints. His is a very pure, rather strict observance, no less solemn in his way than Milton. Not my kind of fellow. And yet. I am now every evening with George Herbert.

It's not wrong, wanting to read poets with whom we feel some personal sympathy. More so even than the great writers of prose, I find the poets I want tend to be the poets with whom I agree. That's not enough of itself, of course. (If it were, I should probably enjoy a great deal more contemporary poetry, and enjoy it more than I do, as it seems mostly these days to be written by perfectly nice people: liberal academics, lesbian amateur gardeners and cute straight boys with thick glasses. Sounds like a lovely dinner party -- vegetarian, of course.) I can read quite conservative, even reactionary historians and philosophers, satirists and journalists, even novelists and disagree without finding their books disagreeable. Poetry is different. Poetry is emotional for me, nearly always, and I need some affinity beyond whatever admiration I might feel for the technical accomplishments of the poem. Not such a bad rule of thumb for reading; to want to like what's read and who wrote it.

But then George Herbert undoes all that. I like him. Beyond the mind-blowing invention and proficiency of his poetry -- and there have been damned few poets in English more capable, I should think -- there is an altogether captivating goodness to him. I've never entirely taken to Donne, for instance, although I recognize him to have been a very great poet, and a greater one than Herbert certainly. I suspect there is always something of the pulpit to everything Donne ever did, or at the very least the lectern, which may explain his extraordinary popularity in these later days with academics. A brilliant mind, exercised by large ideas, but always for me in full vestments, approached only at Mass, or for instruction. Herbert visits. It may be a disservice to Herbert to see him so, as he is far from a cozy kind of visitant; there's cold comfort for me in his Good News. But where Donne seems humble before his God and elsewhere from sensibility of his place in the greater scheme of things, Herbert seems quite genuine in not just his faith but in his forgiving nature. Like Montaigne, Herbert's chief subject is himself; his soul, his struggle, his sin, his hope of Heaven, his redeemer; Jesus Christ. I suppose it's the difference between great sacred music and a simple hymn. It may explain Herbert's apparent popularity with composers, funnily enough.

"O what a cunning guest

Is this same grief! within my heart I made"

That, from his "Confession," and taken something out of context, defines for me what's most troubling for me in reading so good a Christian. I can't but be a little impatient with a world view that generates from griefs more grief, almost as a means to savor solace the more when it's found. Not, of course how Christians would see it, certainly not what Herbert meant.

"Sweeten at length this bitter bowl,

Which thou hast pour'd into my soul"

Or, not to be too glib, just avoid the damned soup. But Herbert isn't always moaning, he sings:

"Blest be the God of love,

Who gave me eyes and light, and power this day,

Both to be busy, and to play."

"O raise me then! poor bees, that work all day,

Sting my delay,

Who have a work, as well as they,

And much, much more."

And he talks, and talks very well:

"He that is weary let him sit.

My soul would stir

And trade in courtesies and wit,

Quitting the fur

To cold complexions needing it."

And he's a friend:

"That I shall mind what you impart,

Look you may put it very near my heart."

And, oh my, but he can write, as here an echo of Shakespeare shows:

"Oh, what a thing is man! how far from power,

From settled peace and rest!

He is some twenty sev'ral men at least

Each sev'ral hour."*

Having just a Pocket Poets edition in which to read further so far, I am being sparing of the whole still, until I can find a nice, big book, complete. Meanwhile, here again in someone I have found, a genius unknown to me and a friend now, thanks again to one little paperback book, copyright 1929, my edition printed in 1957. Even more the point, here then is what I will freely admit is for me a hard read; religious poetry, and yet, having made the venture, I've found such rewards!

I worry a bit that difficult literature, as a category of reading, has too much become the exclusive undertaking of the student and too little the leisure study of the common reader. I worry that we mistake too often now the merely ugly for the complex or the profound. I've been asked again, just this past week if i ever "read anything easy." Please. I worry that we so seldom read anything else. Nothing wrong with reading a mystery novel. I'm reading one now. Why wouldn't I? Should I not also challenge myself? Look in an old book not quite in my usual line? Pick up a writer unlike myself in important ways; like religion, philosophy, expertise, formal interest, rather than congratulate myself, as we are all now so inclined to do, as if it meant anything, for reading something by someone who happens to be from somewhere else, or who looks unlike me, but who writes and thinks no differently, and sometimes no better than I might?

We need to read, now and then, what's difficult for us, for what's good often is, but more than that we need to read what is better than what we might read otherwise and just because we choose to know no better and remember nothing of what we owe the past.

But then I ask a question, all but at random to a dozen people -- admittedly a dozen literate, clever people -- and I find we all of try. We blame ourselves when we fail as well, often as not. Not wrong, I think. Certainly the Right Reverend George Herbert, bless 'im, might approve. He would certainly sympathize.

*A note on these excerpts: form mattered very much to Herbert -- he invented some -- and so the limitations of this space deform his lines unforgivably, so do seek out a proper book to see them as he put them right.

The question was simply, "What was the hardest book you've read?"

Didn't want to be any more particular than that, though nearly everyone I asked asked me to be. A book they'd finished? A book they'd liked, or disliked? Not the point. What I wanted was not so much the titles as the explanations, and those were quite interesting, I thought. When I formulated the question, I hadn't even been thinking about contemporary fiction, for instance, or politics, or violence. I asked coworkers at the bookstore mostly, and a couple of social media friends. Hardly a scientific survey, but then not a very objective question.

Doesn't really need saying, but what's difficult is different, not just from book to book and reader to reader -- though I must say I smiled in recognition more often than not -- but from one experience of a particular book to the next, if there's been more than one. That was something of a happy surprise to me too; how many of us either have made or still intend to make another go at these books. Something in the nature of the serious reader, I suppose, and we all of us are that had the conversation, that even our worst experiences in reading weren't seen as having been wasted. But then, I've said that wrong, haven't I? No one said that what was hard was worst, not one. Moreover, nearly everyone assigned the difficulty not to the text but to reader, though all with some qualifications; to do with age and experience, or other commitments and distractions, and most often, simply time.

I found the whole discussion very reassuring.

I was prompted to this question by reading George Herbert. I'll get back to him, but to tell the thing in the right order, I should start not with him, but with my last vacation, back in October. Every year I go home to Pennsylvania to see the old people. Every year I use the trip as an excuse to buy used paperbacks, something I otherwise almost never do. I always take too many books, naturally. The ones I read in those two weeks, I leave behind, along with anything I might not have much liked. Roughly once a year then, I enjoy buying books I don't intend to keep: mystery novels, light comedies, neglected classics, at least one or two familiar things I mean to reread. It's all ridiculously ambitious and, as there are no consequences to failing, and it's such a negligible financial investment, it's all a bit of a fantasy, really. (Though I must say, I've actually been able to get a fair bit of reading done as my parents have aged and there's nobody much else to be entertained of an evening but ourselves. Early to bed with a book seems the perfect height of indulgence to me nowadays. I needn't even review any of my reading here afterwards, unless I've a mind to. Vacation, you see.)

This year, in addition to the Christies and the Kawabata I never got to and the Orwell essays I barely touched, and for reasons I can not explain, I also picked up the anthology pictured above. Not my period, you understand, The Seventeenth Century, at least, not before now. The book, edited by one Evert Mordecai Clark, was part of a series, and any of the three books after this, The Eighteenth Century, The Romantics, or The Victorians, had I come across one of those, would have been a much likelier choice. I know those last two specially well now, and have at least some experience of the earlier. But before that? Shakespeare, of course, and a bit of Jonson, and then? Mind the gap. I can only think, in the absence of something more familiar, I wanted some poetry, and this one, with both poetry and prose and at roughly six hundred pages, seemed to fit my impulse. Anyway, I bought it. Then I kept reading it.

And I've kept it, the paperback anthology, because it is that good. The early essayists were a revelation and favorites, naturally, from John Earle (1601 - 1665) to Thomas Fuller (1608 - 1661). For the most part, they are just this side of sermons but of such simplicity and good nature as to never feel the drag of preaching. In fact, all the prose of every description, from history to natural science and letters, all of it has a warmth and immediacy I would never have anticipated in what I can't help but think of as a very formal period. Lovely surprise.

It's the poets who dominate though, naturally enough in a book I actually selected for poetry. I was, if anything however, even more resistant to reading some of these for that same reason: piety. Well, I was right about that, but I was also a fool.

It was all to do with Milton, I should think. I never have taken to Milton. His "Paradise" has always been among my very hard books and I've never yet made it. In my mind, he stood not just well above his times, but for them, so I hadn't had much of a look around him before. Like the shadow of some magnificent, coldly intimidating cathedral cast across the whole of Stuart and Puritan England, was that great poem.

But I'd missed out on Robert Herrick ( 1591 - 1674.) He became something of a preoccupation after I got home from my trip. Twenty pages in this book of his Hesperides and we were old friends. I had to buy a proper Oxford edition, and read right through it. He has all the charm and good humor of what I can't help but think of as a slightly older, Tudor England, and nearly none of the Puritan in him. He's eminently likable, like Henry Vaughan (1622 - 1695); musical and no stranger to a good meal or a pretty girl, from the sound of him. For me now, they represent all I'd missed out on, thinking the 17th a century of black-clad churchmen.

But then, there's George Herbert, and George Herbert is hard. Herrick was a clergyman no less than Herbert, but Herbert is harder. Herbert is one of God's great poets, and I don't much care to read about God, specially Herbert's rather bloody-minded Christ. It seems Herbert was a very nice, devout and even dear sort of person, but far from even the unwitting sensualists one so often finds for instance among the Renaissance Saints. His is a very pure, rather strict observance, no less solemn in his way than Milton. Not my kind of fellow. And yet. I am now every evening with George Herbert.

But then, there's George Herbert, and George Herbert is hard. Herrick was a clergyman no less than Herbert, but Herbert is harder. Herbert is one of God's great poets, and I don't much care to read about God, specially Herbert's rather bloody-minded Christ. It seems Herbert was a very nice, devout and even dear sort of person, but far from even the unwitting sensualists one so often finds for instance among the Renaissance Saints. His is a very pure, rather strict observance, no less solemn in his way than Milton. Not my kind of fellow. And yet. I am now every evening with George Herbert. It's not wrong, wanting to read poets with whom we feel some personal sympathy. More so even than the great writers of prose, I find the poets I want tend to be the poets with whom I agree. That's not enough of itself, of course. (If it were, I should probably enjoy a great deal more contemporary poetry, and enjoy it more than I do, as it seems mostly these days to be written by perfectly nice people: liberal academics, lesbian amateur gardeners and cute straight boys with thick glasses. Sounds like a lovely dinner party -- vegetarian, of course.) I can read quite conservative, even reactionary historians and philosophers, satirists and journalists, even novelists and disagree without finding their books disagreeable. Poetry is different. Poetry is emotional for me, nearly always, and I need some affinity beyond whatever admiration I might feel for the technical accomplishments of the poem. Not such a bad rule of thumb for reading; to want to like what's read and who wrote it.

But then George Herbert undoes all that. I like him. Beyond the mind-blowing invention and proficiency of his poetry -- and there have been damned few poets in English more capable, I should think -- there is an altogether captivating goodness to him. I've never entirely taken to Donne, for instance, although I recognize him to have been a very great poet, and a greater one than Herbert certainly. I suspect there is always something of the pulpit to everything Donne ever did, or at the very least the lectern, which may explain his extraordinary popularity in these later days with academics. A brilliant mind, exercised by large ideas, but always for me in full vestments, approached only at Mass, or for instruction. Herbert visits. It may be a disservice to Herbert to see him so, as he is far from a cozy kind of visitant; there's cold comfort for me in his Good News. But where Donne seems humble before his God and elsewhere from sensibility of his place in the greater scheme of things, Herbert seems quite genuine in not just his faith but in his forgiving nature. Like Montaigne, Herbert's chief subject is himself; his soul, his struggle, his sin, his hope of Heaven, his redeemer; Jesus Christ. I suppose it's the difference between great sacred music and a simple hymn. It may explain Herbert's apparent popularity with composers, funnily enough.

"O what a cunning guest

Is this same grief! within my heart I made"

That, from his "Confession," and taken something out of context, defines for me what's most troubling for me in reading so good a Christian. I can't but be a little impatient with a world view that generates from griefs more grief, almost as a means to savor solace the more when it's found. Not, of course how Christians would see it, certainly not what Herbert meant.

"Sweeten at length this bitter bowl,

Which thou hast pour'd into my soul"

Or, not to be too glib, just avoid the damned soup. But Herbert isn't always moaning, he sings:

"Blest be the God of love,

Who gave me eyes and light, and power this day,

Both to be busy, and to play."

"O raise me then! poor bees, that work all day,

Sting my delay,

Who have a work, as well as they,

And much, much more."

And he talks, and talks very well:

"He that is weary let him sit.

My soul would stir

And trade in courtesies and wit,

Quitting the fur

To cold complexions needing it."

And he's a friend:

"That I shall mind what you impart,

Look you may put it very near my heart."

And, oh my, but he can write, as here an echo of Shakespeare shows:

"Oh, what a thing is man! how far from power,

From settled peace and rest!

He is some twenty sev'ral men at least

Each sev'ral hour."*

Having just a Pocket Poets edition in which to read further so far, I am being sparing of the whole still, until I can find a nice, big book, complete. Meanwhile, here again in someone I have found, a genius unknown to me and a friend now, thanks again to one little paperback book, copyright 1929, my edition printed in 1957. Even more the point, here then is what I will freely admit is for me a hard read; religious poetry, and yet, having made the venture, I've found such rewards!

I worry a bit that difficult literature, as a category of reading, has too much become the exclusive undertaking of the student and too little the leisure study of the common reader. I worry that we mistake too often now the merely ugly for the complex or the profound. I've been asked again, just this past week if i ever "read anything easy." Please. I worry that we so seldom read anything else. Nothing wrong with reading a mystery novel. I'm reading one now. Why wouldn't I? Should I not also challenge myself? Look in an old book not quite in my usual line? Pick up a writer unlike myself in important ways; like religion, philosophy, expertise, formal interest, rather than congratulate myself, as we are all now so inclined to do, as if it meant anything, for reading something by someone who happens to be from somewhere else, or who looks unlike me, but who writes and thinks no differently, and sometimes no better than I might?

We need to read, now and then, what's difficult for us, for what's good often is, but more than that we need to read what is better than what we might read otherwise and just because we choose to know no better and remember nothing of what we owe the past.

But then I ask a question, all but at random to a dozen people -- admittedly a dozen literate, clever people -- and I find we all of try. We blame ourselves when we fail as well, often as not. Not wrong, I think. Certainly the Right Reverend George Herbert, bless 'im, might approve. He would certainly sympathize.

*A note on these excerpts: form mattered very much to Herbert -- he invented some -- and so the limitations of this space deform his lines unforgivably, so do seek out a proper book to see them as he put them right.

Saturday, January 26, 2013

Daily Dose

From Horace Walpole: A Biographical Study, by Lewis Melville

WHAT!

"'What! learn more than I am absolutely forced to learn! I felt the weight of learning that, For I was a blockhead and pushed above my parts.'"

From a letter quoted in Chapter One, Early Years

WHAT!

"'What! learn more than I am absolutely forced to learn! I felt the weight of learning that, For I was a blockhead and pushed above my parts.'"

From a letter quoted in Chapter One, Early Years

Friday, January 25, 2013

Daily Dose

Thursday, January 24, 2013

Daily Dose

From The Book of the Duke of True Lovers, by Christine de Pisan, translated by Laurence Binyon & Eric R. D. MacLagan

AND, WITHOUT

"And, without making any excuse, I tell you that, when we had supped, after taking comfits, we drank."

AND, WITHOUT

"And, without making any excuse, I tell you that, when we had supped, after taking comfits, we drank."

Wednesday, January 23, 2013

Daily Dose

Tuesday, January 22, 2013

Daily Dose

Monday, January 21, 2013

Daily Dose

From Religio Medici & Other Writings, by Sir Thomas Browne

ALL THINGS

"All things began in order, so shall they end, and so shall they begin again; according to the ordainer of order and mystical Mathematicks of the City of Heaven."

From Garden of Cyrus, Chapter 5

ALL THINGS

"All things began in order, so shall they end, and so shall they begin again; according to the ordainer of order and mystical Mathematicks of the City of Heaven."

From Garden of Cyrus, Chapter 5

Sunday, January 20, 2013

Daily Dose

Saturday, January 19, 2013

Daily Dose

From The Collected Short Stories Volume 1, by William Somerset Maugham

From The Collected Short Stories Volume 1, by William Somerset MaughamIT WAS

"It was true that she would have liked to marry again, but her fancy turned to a dark slim Italian with flashing eyes and a sonorous title or to a Spanish don of noble lineage; and not a day more than thirty."

From The Three Fat Women of Antibes

Friday, January 18, 2013

Daily Dose

From The Razor's Edge, by William Somerset Maugham

FEUDAL

"'Oh, how it brings back the old days! You people who never stayed with the Radziwills don't know what living is. That was the grand style. Feudal, you know.'"

From Chapter 5

FEUDAL

"'Oh, how it brings back the old days! You people who never stayed with the Radziwills don't know what living is. That was the grand style. Feudal, you know.'"

From Chapter 5

Thursday, January 17, 2013

Daily Dose

From Religio Medici and Other Writings, by Sir Thomas Browne

THERE IS

"There is, I thinke, no man that apprehends his own miseries less than my self, and no man that so neerely apprehends anothers. I could lose an arme without a teare, and with few groans be quartered into pieces; yet can I weepe most seriously at a Play, and recieve with a true passion, the counterfeit griefes of those knowne and professed Imposters."

From The Second Part

THERE IS

"There is, I thinke, no man that apprehends his own miseries less than my self, and no man that so neerely apprehends anothers. I could lose an arme without a teare, and with few groans be quartered into pieces; yet can I weepe most seriously at a Play, and recieve with a true passion, the counterfeit griefes of those knowne and professed Imposters."

From The Second Part

Wednesday, January 16, 2013

Daily Dose

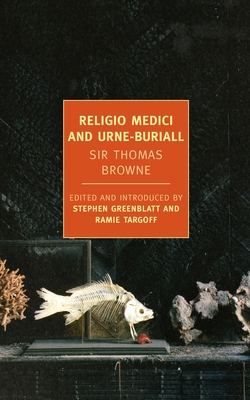

From Religio Medici and Urne-Buriall, by Sir Thomas Browne

I CONFESSE

"I confesse I have perused them all, and can discover nothing that may startle a duscreet beliefe: yet are there heads carried off with the wind and breath of such motives."

From The First Part

I CONFESSE

"I confesse I have perused them all, and can discover nothing that may startle a duscreet beliefe: yet are there heads carried off with the wind and breath of such motives."

From The First Part

Tuesday, January 15, 2013

Daily Dose

Monday, January 14, 2013

Just One

"If I had to read just one, which one?"

Horrible, stupid question. I'm sorry, but it is. "Where should I start?" or "Which would you recommend?" -- either might be the start of a conversation, but that first? The answer to that first question, the honest answer, I can't say, at least when working in a bookstore.

It seems there are still people -- men mostly in my experience, and well-heeled gentlemen at that -- who still seem to feel some strange sense of obligation, a duty, if that word isn't altogether too quaint, to... what? Take a bit of culture, for what ails 'em? Is that it? I don't understand the attitude; art as a bitter pill. Why? We're Americans. There's no shame in ignorance. Who is it that's made them feel they ought to have read something good? "A classic"? Clearly they might read anything they want, or read nothing at all. Wouldn't think it's harmed them much, or at least it's not kept them back in the world, has it? Not reading Penguin paperback classics.

Faced, for example with a shelf of Dickens novels, perhaps knowing very little of Dickens beyond Scrooge, I can even now see how daunting, even impossible all those fat books might seem. Where to start indeed? (I don't even remember where I started, or quite when. Doesn't matter, in my own experience. All that matters, at least all that's mattered to me has been the start. The going on will see to itself once the conversation's going, if it is to. Still, as a bookseller, usually asked to make a recommendation because I have a reputation for not reading much else, Oliver Twist would be my usual suggestion, to friends, or for just good natured people brave enough or curious enough to ask without that pained sigh, that sense of grudging duty. There's a familiarity to Oliver Twist, for most of us, even if not quite as sure as Dickens' Carol. For some readers though, after a bit of conversation, I might suggest something else; say David Copperfield because that book is as easy to love as the author did, as nearest to him, or a later title, like Bleak House for a reader of more difficult things, like some college kid who expects something denser and deeper, or maybe Pickwick Papers or Nickleby if the customer might like something more anarchic and plain funny. For some readers new to Dickens, the best way may be the journalism. It depends upon the conversation, ours, and the one yet to be had with the novelist.)

That's what art is, that conversation with the unfamiliar, with something larger than just our time or our peers, or a clerk in a shop.

Huff puff.

That's the fantasy, isn't it? That honest conversation between equals? Not always, or even often the case. As someone whose job it is to sell books, it is seldom my place to say what one ought to read. It's never my place to question if anyone should.

There's nothing to say that the well-heeled fellow won't like what he buys. Meanwhile, we're grateful for his custom.

I hate the very idea that someone can't read Dickens, or that anyone might not, if they tried. However, I confess, I hate nearly as much the idea that anyone should, that anyone is obliged to do so, or at least to have done. In school, certainly, I suppose, but after that?

Read good things, and then read better things, because the thing is good, because it might be better than what one knows or is used to. What else is art for?!

Myself, I always feel I've come so late to so much that is really wonderful. For everything I read when I was young, because I was sure I would be judged ignorant for never having done so, I am only now grateful, knowing how inadvertent my own education proved to be. How lucky I was, in a way, to know no better. How little I understood what I was doing! Now looking back, I can see the happy accidents that shaped my own taste and interests. (And how woefully wrong I was not only about what was or wasn't good until I found what was better, but how wrong I was about what would matter to other people -- at least until I was able to find like-minded friends, and better guides and teachers.)

Film is worse than fiction, as to what is or isn't worth knowing, or rather it was before the wonders of our own age, when nearly anything from the whole history of movies might be seen by the click of a button or an order made and mailed. If there were few opportunities in my own early life to find the best books, back then there was only the slimmest chance of seeing a movie worth watching. If I've loved some bad books down my days, how many bad movies must I once have watched, enthralled, in front of the television!

Anyway now, I can see so many great things. It is so simple, isn't it?

Here's that metaphoric shelf again, that row of the world's best everything. And where to start? Inadvertence still plays a part, perhaps even more important than with fiction. One book, with a proper introduction if an old one, say, leads logically to the next. To read in one author is to engage in a conversation, and if the author is good, and more, if the author is great, then coming to the end of just his or her length of shelf, not only leads naturally to the next -- or the one before -- but also back to the beginning and, if there's time and a good intention, to a new conversation with an old acquaintance. To read even a little about film, as with any good criticism, helps, but once one sees, say, Un condamné à mort s'est échappé ou Le vent souffle où il veut (1956) -- A Man Escapes, as I did not all that long ago, that can and probably should send someone backwards and forwards with a filmmaker just as with a novelist.

Tonight I watched Les dames du Bois de Boulogne (1945) -- The Ladies of the Bois de Boulogne. Adapted from a story from Diderot's Jacque the Fatalist, this was a smashing 40s melodrama; all shimmering, feminine emotion and fabulous fur hats, fast cars and revenge. The film starred the glorious Maria Casares as a woman who makes the mistake of testing her man -- he fails, of course -- and then there's Hell to pay. (Think Joan Crawford with a script by Jean Cocteau.)

I can't think how I would ever have found this film, had I not decided to see everything ever made by it's director, Robert Bresson. (True, Marie Casares was in my favorite film of all time, Les Enfants du paradis (1945) playing Nathalie, but I hadn't realized that until tonight.) I can't quite say that tonight's movie was nothing like that later masterpiece I'd watched so recently on Turner Classic Movies, but had I not known that the same man made both, I might never have guessed that the director of A Man Escapes had made this one.

I've watched nearly all the feature films directed by Bresson now, renting them one after another and each has been something of a revelation. I can't think of another filmmaker who has so completely understood the dramatic possibilities of a story told in just that frame, frame after frame, each composed in such a strangely natural and yet disciplined way, everything extraneous to the story eliminated. I can't think of anyone who so effectively, mesmerizingly simplified the sound motion picture into something as pure as any silent picture. I can't recommend any of his work highly enough -- nor am I qualified to say how or even what it was he did so beautifully well.

But then here I was tonight watching his second feature, not, as I've said, very like his later work, and yet already an excellent early example of the taste and restraint that would make all his latter stuff so quintessentially cinematic, and so satisfying. There's a lot of rain in this one, for example, and lovers caught, time and again in it. Such a simple, predictable device for driving two people together. The first time it happens, the scene might almost be from any Hollywood picture of the period. But then, there's the poor girl's raincoat. This would be Elina Labourdette, a poor dancer, down-at-heel, finally in love with the man she's meant to ruin, and, walking to meet him in the rain, she looks like Hell. That damned raincoat! It's the only one she got, you see, that and a sad little hat. We've seen her in these time and again by now, and only now, in what looks to be a very real, very cold, somehow very Parisian rain, she's heartbreaking in a way that looks more like something from the New Wave than the Occupation. It's quite startling, and quite wonderful.

And then there's Casares in her triumph, not as Crawford might have been shot in the same scene in some "women's picture" of the day, all statuesque fury on a grand staircase, nostrils flaring in a dazzling close-up, no. Instead, we see Casares through the window of her old lover's car. She's blocked him in his driveway with her own car, and he's frantically trying to maneuver around her. She stands there, as he backs up and pulls forward, again and again, and she goes in and out of the shot, and every time she manages to say something awful and never moves. It's wonderfully claustrophobic, even cruel. The sequence is amazingly modern.

But I can't really talk about all of this in a very meaningful way. Bresson has to be seen. As I've said, the great thing for me is that he can be, nearly all of his work, if not quite in an ideal way, in a cinema, then at least in excellent prints on our big TV.

I won't suggest one Bresson movie, over another. I haven't seen them all yet, and I haven't seen any of them yet more than once except his Joan of Arc.

No one need feel that these movies ought to be seen. I certainly lived a fairly contented life before and might just as easily have continued so without feeling pig-ignorant for not knowing any better. Again, that is just such a ridiculous way to think! No. What I've meant to suggest tonight is how glorious the possibilities of discovery and rediscovery may still be, evan as I approach fifty. There is still so much to see, to read, to read and see again! -- and without once thinking how awful it is that I'd never seen a movie directed by Robert Bresson, until I did.

Horrible, stupid question. I'm sorry, but it is. "Where should I start?" or "Which would you recommend?" -- either might be the start of a conversation, but that first? The answer to that first question, the honest answer, I can't say, at least when working in a bookstore.

It seems there are still people -- men mostly in my experience, and well-heeled gentlemen at that -- who still seem to feel some strange sense of obligation, a duty, if that word isn't altogether too quaint, to... what? Take a bit of culture, for what ails 'em? Is that it? I don't understand the attitude; art as a bitter pill. Why? We're Americans. There's no shame in ignorance. Who is it that's made them feel they ought to have read something good? "A classic"? Clearly they might read anything they want, or read nothing at all. Wouldn't think it's harmed them much, or at least it's not kept them back in the world, has it? Not reading Penguin paperback classics.

Faced, for example with a shelf of Dickens novels, perhaps knowing very little of Dickens beyond Scrooge, I can even now see how daunting, even impossible all those fat books might seem. Where to start indeed? (I don't even remember where I started, or quite when. Doesn't matter, in my own experience. All that matters, at least all that's mattered to me has been the start. The going on will see to itself once the conversation's going, if it is to. Still, as a bookseller, usually asked to make a recommendation because I have a reputation for not reading much else, Oliver Twist would be my usual suggestion, to friends, or for just good natured people brave enough or curious enough to ask without that pained sigh, that sense of grudging duty. There's a familiarity to Oliver Twist, for most of us, even if not quite as sure as Dickens' Carol. For some readers though, after a bit of conversation, I might suggest something else; say David Copperfield because that book is as easy to love as the author did, as nearest to him, or a later title, like Bleak House for a reader of more difficult things, like some college kid who expects something denser and deeper, or maybe Pickwick Papers or Nickleby if the customer might like something more anarchic and plain funny. For some readers new to Dickens, the best way may be the journalism. It depends upon the conversation, ours, and the one yet to be had with the novelist.)

That's what art is, that conversation with the unfamiliar, with something larger than just our time or our peers, or a clerk in a shop.

Huff puff.

That's the fantasy, isn't it? That honest conversation between equals? Not always, or even often the case. As someone whose job it is to sell books, it is seldom my place to say what one ought to read. It's never my place to question if anyone should.

There's nothing to say that the well-heeled fellow won't like what he buys. Meanwhile, we're grateful for his custom.

I hate the very idea that someone can't read Dickens, or that anyone might not, if they tried. However, I confess, I hate nearly as much the idea that anyone should, that anyone is obliged to do so, or at least to have done. In school, certainly, I suppose, but after that?

Read good things, and then read better things, because the thing is good, because it might be better than what one knows or is used to. What else is art for?!

Myself, I always feel I've come so late to so much that is really wonderful. For everything I read when I was young, because I was sure I would be judged ignorant for never having done so, I am only now grateful, knowing how inadvertent my own education proved to be. How lucky I was, in a way, to know no better. How little I understood what I was doing! Now looking back, I can see the happy accidents that shaped my own taste and interests. (And how woefully wrong I was not only about what was or wasn't good until I found what was better, but how wrong I was about what would matter to other people -- at least until I was able to find like-minded friends, and better guides and teachers.)

Film is worse than fiction, as to what is or isn't worth knowing, or rather it was before the wonders of our own age, when nearly anything from the whole history of movies might be seen by the click of a button or an order made and mailed. If there were few opportunities in my own early life to find the best books, back then there was only the slimmest chance of seeing a movie worth watching. If I've loved some bad books down my days, how many bad movies must I once have watched, enthralled, in front of the television!

Anyway now, I can see so many great things. It is so simple, isn't it?

Here's that metaphoric shelf again, that row of the world's best everything. And where to start? Inadvertence still plays a part, perhaps even more important than with fiction. One book, with a proper introduction if an old one, say, leads logically to the next. To read in one author is to engage in a conversation, and if the author is good, and more, if the author is great, then coming to the end of just his or her length of shelf, not only leads naturally to the next -- or the one before -- but also back to the beginning and, if there's time and a good intention, to a new conversation with an old acquaintance. To read even a little about film, as with any good criticism, helps, but once one sees, say, Un condamné à mort s'est échappé ou Le vent souffle où il veut (1956) -- A Man Escapes, as I did not all that long ago, that can and probably should send someone backwards and forwards with a filmmaker just as with a novelist.

Tonight I watched Les dames du Bois de Boulogne (1945) -- The Ladies of the Bois de Boulogne. Adapted from a story from Diderot's Jacque the Fatalist, this was a smashing 40s melodrama; all shimmering, feminine emotion and fabulous fur hats, fast cars and revenge. The film starred the glorious Maria Casares as a woman who makes the mistake of testing her man -- he fails, of course -- and then there's Hell to pay. (Think Joan Crawford with a script by Jean Cocteau.)

I can't think how I would ever have found this film, had I not decided to see everything ever made by it's director, Robert Bresson. (True, Marie Casares was in my favorite film of all time, Les Enfants du paradis (1945) playing Nathalie, but I hadn't realized that until tonight.) I can't quite say that tonight's movie was nothing like that later masterpiece I'd watched so recently on Turner Classic Movies, but had I not known that the same man made both, I might never have guessed that the director of A Man Escapes had made this one.

I've watched nearly all the feature films directed by Bresson now, renting them one after another and each has been something of a revelation. I can't think of another filmmaker who has so completely understood the dramatic possibilities of a story told in just that frame, frame after frame, each composed in such a strangely natural and yet disciplined way, everything extraneous to the story eliminated. I can't think of anyone who so effectively, mesmerizingly simplified the sound motion picture into something as pure as any silent picture. I can't recommend any of his work highly enough -- nor am I qualified to say how or even what it was he did so beautifully well.

But then here I was tonight watching his second feature, not, as I've said, very like his later work, and yet already an excellent early example of the taste and restraint that would make all his latter stuff so quintessentially cinematic, and so satisfying. There's a lot of rain in this one, for example, and lovers caught, time and again in it. Such a simple, predictable device for driving two people together. The first time it happens, the scene might almost be from any Hollywood picture of the period. But then, there's the poor girl's raincoat. This would be Elina Labourdette, a poor dancer, down-at-heel, finally in love with the man she's meant to ruin, and, walking to meet him in the rain, she looks like Hell. That damned raincoat! It's the only one she got, you see, that and a sad little hat. We've seen her in these time and again by now, and only now, in what looks to be a very real, very cold, somehow very Parisian rain, she's heartbreaking in a way that looks more like something from the New Wave than the Occupation. It's quite startling, and quite wonderful.

And then there's Casares in her triumph, not as Crawford might have been shot in the same scene in some "women's picture" of the day, all statuesque fury on a grand staircase, nostrils flaring in a dazzling close-up, no. Instead, we see Casares through the window of her old lover's car. She's blocked him in his driveway with her own car, and he's frantically trying to maneuver around her. She stands there, as he backs up and pulls forward, again and again, and she goes in and out of the shot, and every time she manages to say something awful and never moves. It's wonderfully claustrophobic, even cruel. The sequence is amazingly modern.

But I can't really talk about all of this in a very meaningful way. Bresson has to be seen. As I've said, the great thing for me is that he can be, nearly all of his work, if not quite in an ideal way, in a cinema, then at least in excellent prints on our big TV.

I won't suggest one Bresson movie, over another. I haven't seen them all yet, and I haven't seen any of them yet more than once except his Joan of Arc.

No one need feel that these movies ought to be seen. I certainly lived a fairly contented life before and might just as easily have continued so without feeling pig-ignorant for not knowing any better. Again, that is just such a ridiculous way to think! No. What I've meant to suggest tonight is how glorious the possibilities of discovery and rediscovery may still be, evan as I approach fifty. There is still so much to see, to read, to read and see again! -- and without once thinking how awful it is that I'd never seen a movie directed by Robert Bresson, until I did.

Daily Dose

Sunday, January 13, 2013

Quick Review

Paul Clifford by Edward George Bulwer-Lytton

My rating: 1 of 5 stars

How I wanted to prove the bastards wrong. Unfortunately, how right they were. I recently picked up not one, but two big, handsome volumes from the collected works, thinking I should give the old boy a proper chance again. Cost me nearly nothing, but the time sadly wasted. Here's the novel that named the bad-writing-contest: "It was a dark and stormy night..." What's bad about it turns out to be that that was the last sensible thing he wrote in it.

Bulwer-Lytton hadn't a style so much as a seemingly inexhaustible capacity for the inexact, the exaggerated and the swank. Evidently the man could not write so much as a declarative sentence without decking at least the verb in fancy-dress. Maddening. No one ever says what they can "expostulate." No one ever walks but they "perambulate." No one does anything much, for that matter, that they mightn't better have done in half the words in which he insists they do it. Worse, there's no point to any of it. It's Dickens without a thought, a point, the slightest discernment or deviation from type. What makes the whole business unreadably bad is that the man clearly had nearly every other requirement of a first-rate novelist; character, invention, sympathy, intelligence and tact. What he lacked was taste, any real sense of humor or confidence in the English language.

What a lot of ponderous hooey.

View all my reviews