"I hold any writer sufficiently justified who is himself in love with his theme." -- Henry James

Wednesday, November 30, 2011

Daily Dose

Tuesday, November 29, 2011

Daily Dose

From The Count of Monte Cristo, by Alexandre Dumas, translated by Robin Buss

From The Count of Monte Cristo, by Alexandre Dumas, translated by Robin BussWHILE

"While he was hovering amid these uncertainties, the nightmare of a man kept awake by pain, daylight began to whiten the windowpanes and shed its light on the pale-blue paper under his hands, on which he had just written this supreme justification of Providence. It was five o'clock."

From XC The Encounter

Monday, November 28, 2011

Daily Dose

Sunday, November 27, 2011

Daily Dose

Saturday, November 26, 2011

The Greatest Prodigality

A friend finally convinced me to join Goodreads. I'd heard about it. I'd seen updates and reviews from the site, posted on various social media. Librarians and other booksellers, and even a few customers at the bookstore had mentioned the thing to me. Like a lot of the bookish bits on the Internet, I couldn't quite see, just looking at the thing, what the point might be. The friend who convinced me to sign on basically told me to look for him there. I don't see enough of him -- can't see enough of him ever, as he's handsome as hell -- so this was just another way to stay in touch, I guess.

A friend finally convinced me to join Goodreads. I'd heard about it. I'd seen updates and reviews from the site, posted on various social media. Librarians and other booksellers, and even a few customers at the bookstore had mentioned the thing to me. Like a lot of the bookish bits on the Internet, I couldn't quite see, just looking at the thing, what the point might be. The friend who convinced me to sign on basically told me to look for him there. I don't see enough of him -- can't see enough of him ever, as he's handsome as hell -- so this was just another way to stay in touch, I guess.Once I'd made an account then, of course, there were twenty other people I knew. Again, there were librarians and booksellers, but also a few authors and devoted lay readers, so to say, as well. Yet another virtual community I'm in, though by now, it's pretty much just the same game different fields.

In case you don't know, and might care, the site is yet another virtual hang-out for the bookish. Email updates will tell you what new titles friends are reading, or want to, or what books they may have reviewed -- there's a 5 star system as well as formats for writing notes and or full-length reviews, if so inclined-- and the more friends on the site, the more updates one may see. The site also functions as a kind of reader's diary, or even library catalogue system with which one may make inventories, lists, and all manner of other wonderfully time-wasting things. There are book clubs to be joined, places to promote activities... lord knows what all I haven't even looked at yet.

Most dangerously, there are all manner of quizzes and such like trivia to be play about with, including a perpetual quiz made up of literary questions devised by members of the free site. Within minutes of creating a profile, I was pissing away hours answering questions quaint and clever, obvious and obscure, and skipping the endless Harry Potter rubbish ("In book four, was Hermione's first pubic hair red or russet?" Blah, blah, bloody blah.) Important to remember that many Goodreads members are young readers, but let's just say, about the quizzes, in general, you may trust me when I tell you, the answer to every other question is either Boo Radley, when Little Women's Jo cut her hair, Mr. Darcy's first name, or quidditch.

Read a few more books, people.

The perpetual quiz has also taught me that while I am strangely confident answering most Shakespeare questions, I am wrong roughly as often as I am right. Shocking. Really? Sebastian? And that's from Twelfth Night, not... the other one? Lord.

What Goodreads really is then, is yet another marvelous excuse to do something online only slightly more productive generally than playing solitaire.

Have I mentioned yet that my friend quite sweetly pointed out to me, just days after he'd finally induced me to join, that I'd already committed a social embarrassment by just plowing through hundreds of titles and marking them as "read"? Seems this is seen as a kind of empty brag, and rather like "shouting" in CAPS, or "trolling" in stranger's comments fields. As I tried to explain, I did it to support any books I might actually review on-site, to show I wasn't just a flibbertigibbet who hadn't read but that one book, and so that I might contribute to lists, etc. Oh well. Besides, I like looking through the title recommendations made, I suppose, automatically by some algorithm or another, suggesting that if I liked the poems of Horace, I might also enjoy The Fundamentals of Ballroom Dancing. Actually, however it's done, the recommendations are a fascinating, and constantly renewing pool, a bottomless aquifer of like to like, in biography, and historical fiction, and poetry and on and on. If anything, reviewing the recommended titles is an even more entertaining waste of time than the quizzes or voting on the lists.

I already applied and was accepted by the powers that be, by the bye, as a"librarian" for the site. I decided to sign up for this so as to be able to update and or otherwise modify or improve the entries for individual titles or editions and or authors. I've already scanned in a dozen covers for books I own that didn't show a cover on the site. I've corrected the listed page count of an edition of Walter Scott that happened to be the one in my hand at that time, an edition that ran to 511 pages rather than the bare 259 originally listed for it. Correcting such small errors, and posting those cover illustrations and the like has felt well neigh useful, far more so anyway than anything else I've been doing at Goodreads.

I certainly didn't need another thing to look at besides porn, of an evening, but here we are.

I do think this latest exploration in social media offers me yet another chance to peep into a wider readership than what I might see otherwise, and I've seen some encouraging chatter -- some quite vigorous defences of print, for example, from quite young readers. Most encouraging, that. What has troubled me a bit, as I've already suggested, has been the astonishingly juvenile character of much of what's being devotedly read and reread by grown people, and an enormous reluctance among the young to read complicated prose, let alone poetry, but to be fair, I've seen nearly as much Austen about as anything, and I've already joined a reader's club for the Victorians, and two groups reading Dickens. (Started one too, to encourage people to read the great Boz aloud for his bicentennial this coming February.)

Nothing pointless about that, really.

Daily Dose

Friday, November 25, 2011

Daily Dose

Thursday, November 24, 2011

Daily Dose

Wednesday, November 23, 2011

Daily Dose

Tuesday, November 22, 2011

Daily Dose

Monday, November 21, 2011

Daily Dose

Sunday, November 20, 2011

Daily Dose

Saturday, November 19, 2011

Daily Dose

Friday, November 18, 2011

Mr. Cogito Finds a New Reader

So a friend reads Zbigniew Herbert and now I have to read Zbigniew Herbert? The friend in question is one of those straight men who cook, you know, big, soulful eyes, balding in a gentle way, traveled, an artist -- he reads Polish poetry, for Heaven's sake. Still, I would resist even his recommendation, had we not had an unread used copy come in. Simply put, it's a beautiful book.

So a friend reads Zbigniew Herbert and now I have to read Zbigniew Herbert? The friend in question is one of those straight men who cook, you know, big, soulful eyes, balding in a gentle way, traveled, an artist -- he reads Polish poetry, for Heaven's sake. Still, I would resist even his recommendation, had we not had an unread used copy come in. Simply put, it's a beautiful book.It's true, I judged this book by its cover. It's nearly as attractive, in it's way, as my friend S. I'm already reading the newest translation of Cavafy finally, properly and straight through so I do not need another poet just now. But then I look at the nice new book, and I'm reminded of my friend's dark eyes, and, oh hell, why not? It is a good cover, a great cover maybe. Look at all that uninterrupted black, no title on the front. What there is, is that great photo by Anna Beata Bohdziewicz, of just the author and of the author, just the necessities: a hand, the match, the cigarette, the face -- coming out of the dark. The match-light on his fingertips might be from a Vermeer. And that head! That head is a glorious thing in black and white, isn't it? The mouth's tight on the cigarette, but to my mind at least it suggests just a pause, the brow, ever so slightly knit but not cross, and then the dome and that tightly swirling atmosphere of hair. It looks a large and wise head, doesn't it. The cover tells me I should know the poet, though I don't, didn't anyway, even after the book's been turned in the hand to read the name on the spine. Ah, but I had to pick the book up there, didn't I?

That kind of thing doesn't always, doesn't often work with me. I tend to resent the suggestion that I should know or recognize by sight a writer I don't, specially somehow a poet. (How many poets not long dead would you know just to look at, even poets one likes, might even revere? In every photograph I've ever seen, William Carlos Williams might have been the Grand Sachem of some Midwest lodge, e. e. Cummings, at least in middle age, some city sign-painter at the end of the bar.) Perhaps this cover works for Herbert because, not even looking up, let alone out at me, there's no suggestion of awkwardness, no introduction offered or recognition expected. Just a handsome fellow of a certain age, lighting up in the dark. It's intimate already, but observed, objective. Anyway, I like it.

I like too that that shiny black book jacket, even before I've put a mylar cover over it, even though the copy is unread, the book's already showing fingerprints, and little scratches, imperfections, though I've cleaned it carefully and the book is new. Normally, I find a design with too much solid color, let alone a solid black or a solid white, off-putting. I know how good it must look at the editorial meeting, but I sell books. I know how quickly and how bad a book can look as soon as it's come off a truck, let alone after that clever design has lived for a while shifting on a table and coming on and off of a shelf. But, with this book, I don't know why, I like it. I like the evident imperfections in the black. I like the subtle whorls and buff smudges that the shiny new mylar somehow accentuates. I like the perfect design undone already, if subtly.

I wouldn't care about any of this though, If I didn't want to sit and do nothing tonight but read more of this book. I wouldn't be staring at Herbert's face, if I didn't want to keep reading Herbert's words. (Even that name! The poet, Herbert, for me means the Welsh divine, George Herbert, 1593 - 1633, you know, the Herbert of The Flower: "Thy word is all, if we could spell." So how then, this Polish fellow, come to be "Herbert"?)

Without knowing much more than what I read in the translator's introduction -- mention of C. P. Cavafy as an influence just for a moment's serendipity -- and I'm off.

Without knowing much more than what I read in the translator's introduction -- mention of C. P. Cavafy as an influence just for a moment's serendipity -- and I'm off.May I say, right off, I like the length of the individual poems? I know that's an odd thing to admire, and I'm not prepared to defend the statement in any educated way, but the best I can say is that the lines, at least in English, are blocked in a a pattern that's both immediately sensible and satisfying to say, both good things to me. Witness this, all but at random, from "Mr. Cogito on Magic":

Joe Dove dreamed

that he was a god

and a god nothingness

he fell slow as a feather

from the Eiffel Tower

Isn't that simple and good? Yet there's a bit of mystery to the thing too, and not, I should think, I would hope, just from the translation.

But back to my point and the length of the poems. Of the poems I've read, and I've read about half the book already, the few that are organized in prose paragraphs, as well as the more usual stanzas of varying lengths, none that I've read are longer than five short lines, all the poems run to a page, or two and a bit at most. None seems defined by the page, and while I can see some longer poems ahead, starting with those written after 1986 it seems, I can see more poems that have larger parts, but my point at least is simply this, that every poem has a natural breath to it, as well as a finished thought, or at least a completed question if not always a clear answer.

How I like that idea! Cavafy has a narrative -- both a short narrative or scene in each poem, and a larger narrative that makes reading his poems sequentially very much a story. Not that Cavafy's narrative progresses, you understand. It doesn't, really. The nights and afternoons and encounters with lovers, these just repeat and vary, more like a dance or a piece of music than a novel, but the music suits him, the poet, and his suits me. (The newest translation's good, by the way.)

I mention how I've been reading Cavafy because now I'm reading Herbert (who read Cavafy) and he's made a narrative too, though it's neither so intimate nor as repetitive as Cavafy's. Instead, with or without the regular figure of "Mr. Cogito" through whom he often addresses the reader, Herbert talks and talks and talks. No, no, it's wonderful, believe me. If a Cavafy poem can feel like some miniature Arabian Night's Tale, something told over coffee, with just a palm fan to stir the air -- sorry, can't be helped -- then these one-sided conversations of Herbert's feel like they last just the length of that cigarette he's lit on the books cover. Many if not most of these poems, even the ones that end, as say even the relatively long poem, "Mr. Cogito Thinks About Blood" does, on a very strong, even a violent image, all have a shrug between them:

blood

swims on

crosses the body's horizon

the borders of imagination

-- looks like there'll be a flood

And then the next poem, on the facing page, starts:

Sunday

early afternoon

a hot day

years ago

in far-off California --

leafing through

The Voice of the Pacific

Mr. Cogito

received the news

of the death of Maria Rasputin

daughter of Rasputin the Terrible

Yes? That seems to me something distinctly something, presumably Polish, that shrug. Doom. And then... shrug, and another day, another poem, another cigarette. (With Cavafy, if you'll indulge me in this conceit just a minute more, it's just an eyebrow up at the end of each poem.)

I never know quite how to say what I mean to about poetry. I haven't any training in it, no proper education in it at all. Why I write about it so infrequently frankly, even as I read more than I've ever done. So what I've just written may be as foolish as it must sound to anyone who would know how to say what I mean to, to a poet, for instance. My apologies. All I meant to suggest was that as much or more than the cleverness in these poems, and it is eminently clear what a clever fellow this Herbert was, I really very much like what I'll call for want of a better word Herbert's voice. I like the calm of it, and the brevity and sly sophistication of expression that conveys so much charming disdain in, for example, these last lines of that last poem I gave the start of above, "Mr. Cogito and Maria Rasputin -- an Attempt at Contact."

O Maria

-- Mr. Cogito thinks

Maria distant chatelaine

with plump red hands

No one's Laura

On behalf of the lady, I wince even as I smile. As does Herbert, by the way, smile, in almost every other picture than the one on the cover of his collected. In almost every photo I've seen so far, Herbert is smoking, yes, but just as likely he's smiling. I like poets that do both.

You were saying, Mr. Cogito?

Daily Dose

Thursday, November 17, 2011

Daily Dose

Wednesday, November 16, 2011

Daily Dose

Tuesday, November 15, 2011

Daily Dose

Monday, November 14, 2011

Daily Dose

From From Absinthe to Zest: An Alphabet for Food Lovers, by Alexander Dumas

From From Absinthe to Zest: An Alphabet for Food Lovers, by Alexander DumasRECIPE

"Pieuvre frite * Fried octopus

Cut your octopus into pieces, roll these in flour, slip them into boiling fat, remove when cooked, and you will have something similar to fried calves' ears, with a light taste of musk."

From Page 56

Sunday, November 13, 2011

Daily Dose

Saturday, November 12, 2011

A Melancholy Truth

Here's a sorry state of things. While I was back in the hometown, visiting with the old people, almost every day I drove into town to go to the library and check my email on one of the public computer stations there. Wonderful service. Indeed, the community library back home is now an altogether brighter and friendlier establishment, even much improved from what it was just a few short years ago, and nothing like the dusty knot-hole of a place I remember from childhood.  The handsome new interior of the library, and the building as a whole, is filled with light. The furnishings and appointments no longer suggest salvage or at best the second hand, and the computers, I was particularly pleased to see, were modern, fast and well regulated by a bright and attentive staff. It would not be too much to say that I actually looked forward to going to the library every day while I was home. Never thought I would be able to say any such thing.

The handsome new interior of the library, and the building as a whole, is filled with light. The furnishings and appointments no longer suggest salvage or at best the second hand, and the computers, I was particularly pleased to see, were modern, fast and well regulated by a bright and attentive staff. It would not be too much to say that I actually looked forward to going to the library every day while I was home. Never thought I would be able to say any such thing.

It is well established by now that I do not think much of public libraries in anything but the abstract. The idea is a vital one. My actual experience of most public libraries, large and small, in almost every place I've lived has been, at best, a mixed bag. In my experience, well-off communities have nicer library buildings, better art, etc., but are no more guaranteed an interesting, or even adequate collection of books than their poorer relations in smaller community and or county systems. If anything, the pressure to keep current with new technologies and the like, while improving systems like inter-library loans, have only further compromised the collections of even the greatest public libraries I've known personally (like Seattle and San Francisco, ) so that traveling the stacks in even the biggest public libraries can now feel like shopping in a thrift shop. It's ugly, and depressing to think of what may well have been discarded to make room for meeting halls, mobiles, and grand staircases leading essentially to... cubicles.

The public library of my childhood was dark, unfriendly, dirty and antiquated even by the standards of the day. The women who worked there were mean, most of 'em, no other word for it, or they were just girls who might just as cheerfully volunteered at summer Bible camp. None the less...

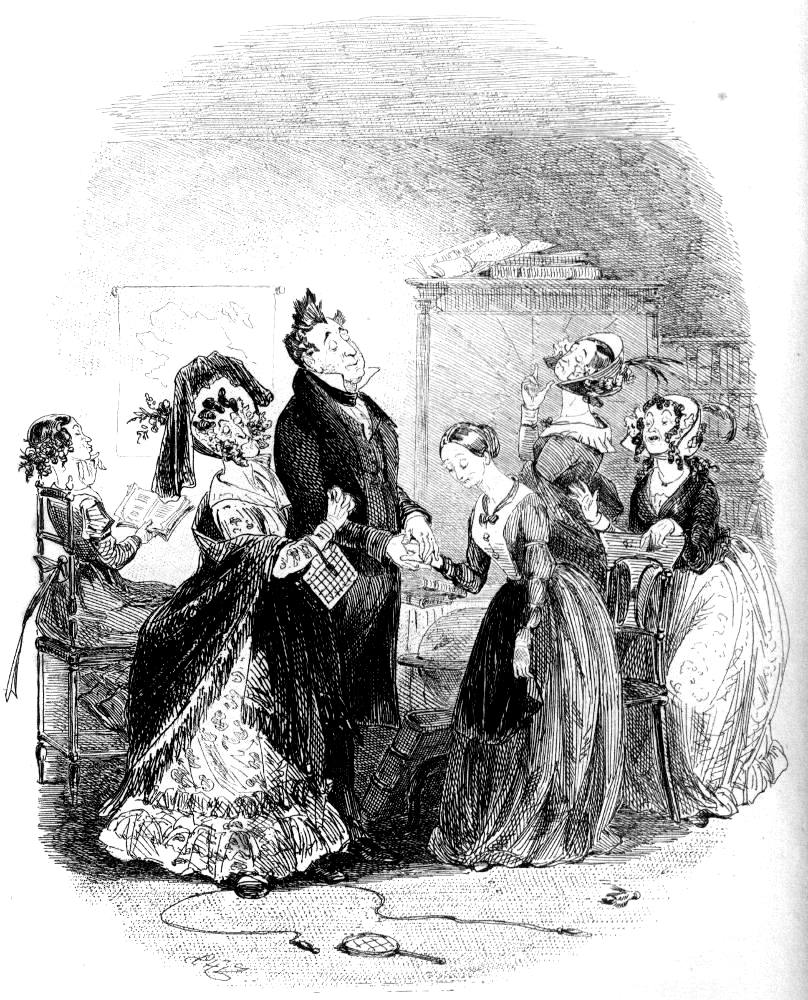

I read Cervantes for the first time in dusty corner of that old building, and Dickens in another, that last in the summer, with only one of those incredibly noisy big circulating fans to keep the place cool. Well, now here's the sorry bit. When I was waiting for my turn at one of the very busy computer terminals, I strolled around the place, admiring this and that, and checking out the inventory, as it were. As with all my explorations in public libraries over the past few years, I did not see nearly enough books. Just me, maybe. What was painfully true was that the state of some of the inventory was pitiable. This then the whole shelf of Dickens, such as it was.

This then the whole shelf of Dickens, such as it was.

This is just tragic. Donated book club editions, in cheap cardboard covers, ancient bits and pieces from broken sets, and most if not all of these old books hopelessly broken themselves. This, the sorry state of The Christmas Books.

This, the sorry state of The Christmas Books.

Won't do. Now, I'm not the sort of person who makes donations to public libraries. I now longer use public libraries much if at all, except it seems on vacation. Moreover, as a used books dealer, I have seen too often and first hand the unhappy consequences of most book donations to anything other than the annual book sales organized as fund-raisers. I've personally seen beautiful old books, in some cases rare and valuable books, donated through the front door of a public library, and promptly tossed out the back door and into a dumpster by staff either ignorant of their value or too stupid or lazy to bother ascertaining just what value, if any, an old book might have. (I'm also convinced that most special collections librarians are just silly snobs. I've seen perfectly common books displayed under glass because they were part of a donation from some forgotten potentate, and valuable books treated like back-issue magazines, covered in stickers and ink and dumped in bins like kindergarten toys.) Hell, I've seen a book purchased for a dollar at a library sale, sell out of a used shop a week later for enough money that the sale of that one book that might have bought the library from which it came... a new computer.

I do not recommend trying to give a librarian a book. I sympathize with the librarians, I do. Most books people try to give them are probably every bit as useless and unappetizing as many of the books those same people have probably already tried to sell some used books dealer. Still, at least the dealers will take a look...

But, anyway, what the hell? All I could do was try, right? I happened to know where a perfectly wonderful, unread, complete set of The Oxford Illustrated Dickens could be had, cheap. The Great Man's birthday is just around the corner. The folks I talked to at the library about this seemed genuinely enthused. Worth doing, I thought.

So this then is an experiment, as well as part of what I hope will prove a larger effort to mark of the occasion of Charles Dickens' Bicentennial. Despite my prejudices, and my past experience, I want to thank the hometown library for the use of the joint, and maybe put Dickens into the hands of some other little bumpkin. Worth doing?

The handsome new interior of the library, and the building as a whole, is filled with light. The furnishings and appointments no longer suggest salvage or at best the second hand, and the computers, I was particularly pleased to see, were modern, fast and well regulated by a bright and attentive staff. It would not be too much to say that I actually looked forward to going to the library every day while I was home. Never thought I would be able to say any such thing.

The handsome new interior of the library, and the building as a whole, is filled with light. The furnishings and appointments no longer suggest salvage or at best the second hand, and the computers, I was particularly pleased to see, were modern, fast and well regulated by a bright and attentive staff. It would not be too much to say that I actually looked forward to going to the library every day while I was home. Never thought I would be able to say any such thing.It is well established by now that I do not think much of public libraries in anything but the abstract. The idea is a vital one. My actual experience of most public libraries, large and small, in almost every place I've lived has been, at best, a mixed bag. In my experience, well-off communities have nicer library buildings, better art, etc., but are no more guaranteed an interesting, or even adequate collection of books than their poorer relations in smaller community and or county systems. If anything, the pressure to keep current with new technologies and the like, while improving systems like inter-library loans, have only further compromised the collections of even the greatest public libraries I've known personally (like Seattle and San Francisco, ) so that traveling the stacks in even the biggest public libraries can now feel like shopping in a thrift shop. It's ugly, and depressing to think of what may well have been discarded to make room for meeting halls, mobiles, and grand staircases leading essentially to... cubicles.

The public library of my childhood was dark, unfriendly, dirty and antiquated even by the standards of the day. The women who worked there were mean, most of 'em, no other word for it, or they were just girls who might just as cheerfully volunteered at summer Bible camp. None the less...

I read Cervantes for the first time in dusty corner of that old building, and Dickens in another, that last in the summer, with only one of those incredibly noisy big circulating fans to keep the place cool. Well, now here's the sorry bit. When I was waiting for my turn at one of the very busy computer terminals, I strolled around the place, admiring this and that, and checking out the inventory, as it were. As with all my explorations in public libraries over the past few years, I did not see nearly enough books. Just me, maybe. What was painfully true was that the state of some of the inventory was pitiable.

This then the whole shelf of Dickens, such as it was.

This then the whole shelf of Dickens, such as it was.This is just tragic. Donated book club editions, in cheap cardboard covers, ancient bits and pieces from broken sets, and most if not all of these old books hopelessly broken themselves.

This, the sorry state of The Christmas Books.

This, the sorry state of The Christmas Books.Won't do. Now, I'm not the sort of person who makes donations to public libraries. I now longer use public libraries much if at all, except it seems on vacation. Moreover, as a used books dealer, I have seen too often and first hand the unhappy consequences of most book donations to anything other than the annual book sales organized as fund-raisers. I've personally seen beautiful old books, in some cases rare and valuable books, donated through the front door of a public library, and promptly tossed out the back door and into a dumpster by staff either ignorant of their value or too stupid or lazy to bother ascertaining just what value, if any, an old book might have. (I'm also convinced that most special collections librarians are just silly snobs. I've seen perfectly common books displayed under glass because they were part of a donation from some forgotten potentate, and valuable books treated like back-issue magazines, covered in stickers and ink and dumped in bins like kindergarten toys.) Hell, I've seen a book purchased for a dollar at a library sale, sell out of a used shop a week later for enough money that the sale of that one book that might have bought the library from which it came... a new computer.

I do not recommend trying to give a librarian a book. I sympathize with the librarians, I do. Most books people try to give them are probably every bit as useless and unappetizing as many of the books those same people have probably already tried to sell some used books dealer. Still, at least the dealers will take a look...

But, anyway, what the hell? All I could do was try, right? I happened to know where a perfectly wonderful, unread, complete set of The Oxford Illustrated Dickens could be had, cheap. The Great Man's birthday is just around the corner. The folks I talked to at the library about this seemed genuinely enthused. Worth doing, I thought.

So this then is an experiment, as well as part of what I hope will prove a larger effort to mark of the occasion of Charles Dickens' Bicentennial. Despite my prejudices, and my past experience, I want to thank the hometown library for the use of the joint, and maybe put Dickens into the hands of some other little bumpkin. Worth doing?

Daily Dose

From Cousin Pons, by Honoré de Balzac. translated by James Waring & Ellen Marriage

From Cousin Pons, by Honoré de Balzac. translated by James Waring & Ellen MarriageAND THIS

"And this in a time when advertising is all powerful; when we gild the gas lamps in the Place de la Concorde to console the poor man for his poverty by reminding him that he is rich as a citizen."

From Page 258, Saintsbury Edition