"I hold any writer sufficiently justified who is himself in love with his theme." -- Henry James

Friday, September 30, 2011

Daily Dose

Thursday, September 29, 2011

Daily Dose

Wednesday, September 28, 2011

Daily Dose

Tuesday, September 27, 2011

Daily Dose

Monday, September 26, 2011

Daily Dose

Sunday, September 25, 2011

Daily Dose

Saturday, September 24, 2011

Daily Dose

Friday, September 23, 2011

Clerihew for the 87th.

Daily Dose

Thursday, September 22, 2011

Daily Dose

Wednesday, September 21, 2011

Daily Dose

Tuesday, September 20, 2011

Daily Dose

Monday, September 19, 2011

Daily Dose

Sunday, September 18, 2011

Daily Dose

Saturday, September 17, 2011

Daily Dose

Friday, September 16, 2011

Daily Dose

Thursday, September 15, 2011

Daily Dose

Wednesday, September 14, 2011

Daily Dose

From Love Conquers All, by Robert Benchley

From Love Conquers All, by Robert BenchleyGLADHAND

"Only Mrs. Abraham Lincoln and Ralph Waldo Emerson neglected to register extreme pleasure at being approached by a smiling lad. Both Mrs. Lincoln and Emerson were failing in their minds at the time, however, which satisfactorily explains their coolness, at least for the author."

From Mr. Bok's Americanization

Tuesday, September 13, 2011

Daily Dose

From A Journal of the Plague Year, by Daniel Defoe

From A Journal of the Plague Year, by Daniel DefoeONE OF

"One of the worst Days we had in the whole Time, as I thought, was in the Beginning of September, when indeed good People began to think, that God was resolved to make a full End of the People in this miserable City."

From Pg. 101, Oxford edition

Monday, September 12, 2011

Daily Dose

Sunday, September 11, 2011

Daily Dose

Saturday, September 10, 2011

Daily Dose

Friday, September 9, 2011

Daily Dose

Thursday, September 8, 2011

Daily Dose

Wednesday, September 7, 2011

Daily Dose

Tuesday, September 6, 2011

d'Artagan on the Dead End Road

There's a famous passage in David Copperfield __ that most autobiographical favorite of the novelist's books -- in which the eponymous hero remembers time spent in his late father's library, his "refuge." When I found this passage again, in Quiller-Couch's Oxford Book of English Prose, I read it aloud here, for the pure plangent pleasure of it, and because it spoke to me of my own books, and the favorites of my own childhood. Of his father's books, David says, "They kept alive my fancy, and my hope of something beyond that place and time..." Just so.

There's a famous passage in David Copperfield __ that most autobiographical favorite of the novelist's books -- in which the eponymous hero remembers time spent in his late father's library, his "refuge." When I found this passage again, in Quiller-Couch's Oxford Book of English Prose, I read it aloud here, for the pure plangent pleasure of it, and because it spoke to me of my own books, and the favorites of my own childhood. Of his father's books, David says, "They kept alive my fancy, and my hope of something beyond that place and time..." Just so.The obvious and elsewhere acknowledged influence on Dickens of the books from "that blessed little room" has no doubt been much studied. The scholars may have at it. For me, as for the novelist, it is the memory of the friends met and made in good books, rather than always the the prose they stood up in, to which I have reason to recur. It is odd -- or perhaps it isn't -- how many works of fiction have in them Characters I have come to see as friends, of whom I have fond memories and the company of whom I still seek. David's list is long and happy: "Roderick Random, Peregrine Pickle, Humphrey Clinker, Tom Jones, the Vicar of Wakefield, Don Quixote, Gil Blas, and Robinson Crusoe... " I am now acquainted with all these famous fictitious gentlemen myself. (All that is but Lesage's hero, whom I have yet to meet, except in other company.) It must be admitted however that as a boy, unlike Dickens and his David, of these, I'd met all only Crusoe. Still, I had many such friends in my own childhood. Like Master Copperfield, I had only to look to my books to find familiar companions. Among my first friends I would number The Patchwork Girl, Huck & Jim, the Musketeers, Rat & Mole & Mr. Toad. The substance of these imaginary friends may be treated as having a reality not so much independent of the words and pictures from which they were made, I think, or even just in consequence of the genius of their making, but as characters in my own story. I traveled first to OZ, for example, in books borrowed from a neighbor, almost before I could read the words. I knew the characters by sight, from the marvelous illustrations of W. W. Denslow and the great John R. Neill. By the time the conversation and adventures of these remarkable people opened to me, I already knew them all, or nearly all, by sight. The Musketeers were as real to me from first acquittance as any friends made at school and if anything, better and more loyal company. (This is no reflection on the friends I had, from school, and the Scouts, the Grange and so on. We lived just far enough in the country that I could not always go to friends as easily as all that, at least until I was old enough to ride my bike the four miles into town.) I have memories of myself -- at nine, would it have been? -- exploring Crusoe's island, through hay-fields, and down among the tall reeds and cattails, by the creek. (Friday, now I come to think of it, was probably the first black man I ever knew. Huck's Jim, the second.)

How and when, for example, one first makes the acquaintance of Betsey Trottwood and Mr. Dick, or of Huck Finn, for that matter, colors ever after the pleasure of each new encounter, just as it would meeting again some memorable personage or bosom friend from childhood, whatever revolutions may have been made in or around us between. As Selden said -- first? -- "Old friends are best", but, in fairness, it might be better to say our memories may be kindest the longer they last. Only the friends who have stood by us and come back to us much as we remember them: just as much fun, just as dear, just as funny, may be said to be true, no matter where we find them again.

I was reminded of this, reading Thackeray a few months back, in an essay of his, a review really, called "A Box of Novels." In it, Thackeray blasts away at various now forgotten targets, all new books of the day, but then he gets to "Boz." The argument is made that the best literature is written not for posterity, or what Thackeray calls "futurity"; that dimly anticipated review of "big-wigs" who are always sure to decide such matters, and like as not get them wrong, but rather, Thackeray argues persuasively enough, the best literature is made just to please the audience for whom the writer writes; addressing not the reviewers or the academics, but the reader. As Thackeray reminds us, irrespective of critical analysis or complaint, a new book, as even Dickens' A Christmas Carol was in 1844, may speak so persuasively to the hearts of it's first readers as to be sure of readers ever thereafter. Thackeray knew a classic when he saw it (and was willing to endorse Dickens' little Christmas book as such, despite whatever rivalry he might have felt with its author. Good man.)

I decided this year not to bring favorites from my childhood with me, as I did the last time home to Pennsylvania. At least two or three of the books I did bring, I've read before, and some a very long time ago, but none from childhood or with any special association with "home." No Dickens this time, and no Twain. Nevertheless, I wonder, being back now in my parents' house, in what was my old bedroom, looking out what was my window to the fields and forests of my childhood, I might not meet with old friends anyway.

When I got home and settled after a ridiculously long day in airports and on the road, I went for a little walk about in the neighborhood, if so empty a spot can be called that, and strolled up to the dead end road above where my parents live. The weeds on either side of the blacktop are taller than I am. No great thing, even in a weed to be taller than me. Still, for a moment in the fading light of the early evening, I was reminded what it was to be but only so high in relation to the world around. When I'd walked down over the slope of the road, nearly to where it ends, I thought I might just find such a one as d'Artagnan striding through the reeds, his friends coming up beside him.

"They walked arm in arm, occupying the whole width of the street and taking in every Musketeer they met, so that in the end it became a triumphal march. The heart of D’Artagnan swam in delirium; he marched between Athos and Porthos, pressing them tenderly."

As I walked back, as the grass moved in the breeze, I might have seen Hugh Lofting's Dr. Dolittle with Polynesia on his shoulder, the Pushmi-pullyu walking, one way or the other behind him. Howard Pyle's Arthur might have come riding out of the woods behind my father's pasture fields.

The point of all this fantastic meandering, if there needs to be one, is that all these characters are still very real to me, even without the books immediately to hand. Sadly, they are not perhaps as real to me as they were when I first made their acquaintance in these places, but they are real to me still. Nothing I may have read about, say, Dickens or Twain, no critical explanation of the style or power of their books, made the people in those books either more or less real to me since. I just got older. Things take longer now for me to do; my reading is slower now and I like to think, more deliberate. Maybe, maybe not. My imagination, certainly, takes more effort to work. But I only have to see the tree I sat under to read the book, to see N. C. Wyeth's picture of Long John Silver. "To me he was unweariedly kind..."

Now, though I'm happy with all the books I brought with me, I rather wish I'd had Treasure Island to read under that tree, or had The Three Musketeers with me tonight in the weeds to read, at least until Mum called me in for supper.

Daily Dose

Monday, September 5, 2011

Packing My Bags

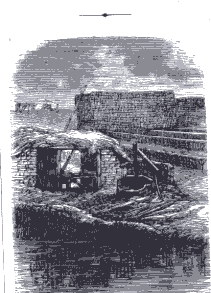

That's the old family house and homestead above, in a photo I took as a kid. Hasn't changed much. There are more and bigger trees now. Otherwise? Dish instead of aerial. Still no bookstore back thereabouts though. Been tried a few time over the years, but never took for very long. Not bookish people back there really. Not so's you'd know, anyway. That means carrying my own books when I go back.

That's the old family house and homestead above, in a photo I took as a kid. Hasn't changed much. There are more and bigger trees now. Otherwise? Dish instead of aerial. Still no bookstore back thereabouts though. Been tried a few time over the years, but never took for very long. Not bookish people back there really. Not so's you'd know, anyway. That means carrying my own books when I go back.The idea is to have options once I'm there. It's not like I'll have much time to myself. I never do when I'm back home. There to visit, after all, not to just sit under a tree and read. Still, there is always a chance of that, too. There'll be nobody there this time but my folks, and my brother across the way. My husband's been and back to Pennsylvania this year already. He went in July, when I couldn't manage it by the bookstore's schedule. My sister was up from Texas already too, with one of the nephews, and so I've missed them as well. Should be then a pretty quiet visit, as visits go. Still, when I read, it will probably be in the mornings, or what now passes for the morning in my parents' house; can take quite a time to get up and stirring anymore, which is fine by me. Generally, my father will be up and breakfast ready before either my mother or me. At some point, out of boredom no doubt, he'll be off to buy a paper and a lottery ticket, maybe the day's groceries, while my mother's still getting ready for the day. After I've showered and before she's ready, I'll have an hour or so in which to read. Last thing at night, after I've retired to my own room, I'll read for awhile as well. I can count on that. That'll be about it, for reading, though I know that there are always unexpected minutes, even hours, when I will find a book good company.

So I've scouted out some old, cheap paperbacks to take with me. I always try to travel with books I intend to leave behind. Seems safest to not have anything with me I should miss. I like old paperbacks anyway; meaning anything with a price on it of less than a dollar and perhaps a cover I actually remember from the first time I read the book, if I have done. The Agatha Christie I found, I probably have read. Pretty sure I read all or nearly all of Miss Marple. Luckily though, I would seem to be entering those middle years when it seems to matter very little -- at least with mysteries -- if I've read them already or not. A Pocket Full of Rye certainly sounds like something I should have read twenty years ago or more when I was reading Christie from every yard-sale where I could find her. The quoted reviews seem to suggest that this is among her best. Well, before I packed it, I read up to the first murder and none of it is remotely familiar, even from television Marples, so into the bag it goes. I've got magazines for the flight, and even though it is a red-eye, I may start the Christie before I get to Pennsylvania. Such fun.

Also in the pure fun category, I've picked up an Eric Ambler, Background to Danger, a.k.a. Uncommon Danger. Never read this one, though with Ambler's formula it isn't always easy to tell what one may or may not have read. Basically some relatively innocent fellow gets tangled with spies. This time, it's a journalist down on his luck. What makes Ambler satisfying still is first how cleverly he incorporated the actual politics of the day (this novel having been written and set just before the start of the Second World War) and a perfect British sangfroid, much copied I should think by later writers like Ian Fleming and John le Carré. (To what extent the perfect gentleman spy was the invention of Maugham and the rest rather than an actual fact, I'm not prepared to theorize. Don't much care. I just like how such stories read, specially when I'm on vacation.)

For something of a more serious quality, I found an old double reissue of Evelyn Waugh, with both A Handful of Dust and Decline and Fall in one fat little paperback. There's an excellent movie of "Dust" from a few years ago, and between that and having read the book when I was reading through most of Waugh, I've never thought to reread it. However, my growing curiosity to read anything other writers might have had to say or write about Dickens has had me thinking about this particular novel lately. Anyone who's read the book, or seen the movie, will remember that the novels of Charles Dickens figure rather prominently, and devilishly, in the second half of Waugh's book. Not perhaps the most flattering portrait of a Dickens enthusiast, but an important one. If for no other reason then, I thought about packing this book. I read the first chapter and was reminded just how good it is. Likewise, Decline & Fall, which I know I haven't read in close to thirty years. Very different book; earlier and more obviously silly, but all the better for that when paired with such a more serious later novel. Into my bag the book goes.

Finally, having searched high and low for a used paperback of Trollope and finding nothing but Barchesters I don't wish to read again so soon, I finally settled on taking my Oxford hardcover copy of The Small House at Allington just because I've wanted to get back and finish all the Barchester books for a very long time now and never got to this one, the one with the marvelous Lilly Dale. Breaking my own rule then about only taking books I'm perfectly content to leave in an airplane, I carefully packed this one at the bottom of the bag, so as not to lose it easily. Maybe by the time I'm flying home, I'll have it out to read on the plane. By then though, I ought to be done with the others.

There aren't that many calls to make anymore when I go "home." Simplifies my schedule while I'm there. And, it gives me a little more time to read. About 650 pages to that Trollope, so we'll see. Not a lot else to do there, come the quiet. That's just fine, mind you.

Daily Dose

Sunday, September 4, 2011

Daily Dose

From The Portable Henry James, edited and introduced by Morton Dauwen Zabel

From The Portable Henry James, edited and introduced by Morton Dauwen ZabelPURE

"In all Mr. Dickens's stories, indeed, the reader has been called upon, and has willingly consented, to accept a certain number of figures or creatures of pure fancy, for this was the author's poetry."

From The Limitations of Dickens

Saturday, September 3, 2011

Daily Dose

Friday, September 2, 2011

Nearly There

Quilp has had his triumph and Kit is in jail. Mr. Richard Swiveller's taken to his bed. The world is out of joint and there's worse, much worse to come. From this point on the story goes quickly; in fact, the plot runs at such a pace for awhile that, like the poor Marchioness, one just has to get on and hold on until it stops. Everything that happens from here, good and bad, happens fast, faster even I should think the second time. One reason I've been going intentionally slow this time, taking my time. I'll finish the book tonight. I have read it before, if I haven't yet made that clear. This time though, I'm reading it to a different end, so to say. In fact, this time, I read the ending first, the way some people insist on reading mysteries, a practice of which I do not approve, generally. This time I've actually read the book just to get to where I am now, to just what comes after this, to see for myself what I now think of the book, its end, and what came after. I'm reading the book that slowly, as slowly as I've ever read a novel by Dickens, because this time I'm trying to read it as it might have been read that first time, in parts. I want very much to see for myself if I might be made to understand the end as the Victorian reader did, as readers as different as Poe and Carlyle read it. I want to see, now I'm older than Dickens was when he wrote it, if, as was true when I first read the book as a teenager, I am still with Oscar who famously said that "One would have to have a heart of stone to read the death of little Nell without dissolving into tears...of laughter.' We shall see. I'm nearly there again. The Old Curiosity Shop is nearly done.

Earlier this year, I reread Hard Times for the first time. I specifically undertook to read one of the novels of Dickens I'd liked the least when I read them first. Likewise, The Old Curiosity Shop. The former seemed to me a better book than I'd remembered, but still far from likely to ever be a favorite. It was too dry, too hot, too brick-hard. Its comparative brevity could not make it any better. But I was glad to have read it again, as an adult, when I could, I think, better appreciate the rhetorical skill with which Dickens made a sermon, not so much of the sins of the mills as I was taught, but of the neglect of imagination, of story, of joy, and the peril of denying these things to anyone, high or low, rich or poor. I don't know that I will ever need to read Hard Times in its entirety again, though as I've said, I'm glad I did. I think now, I will read The Old Curiosity Shop again. I can see myself, given sufficient time, reading it again more than once. I am amazed at it, and at myself for having avoided it so long.

I had thought to make this my assignment, as it were, when I took my annual trip back East to see the elderly parents. The dates for that trip became confused and impossible until now. As a result, I started the book sooner than I had intended, and now I rush to finish it again before I have to leave. What started then as a task, has become a pure pleasure. Imagine that.

Years ago, I worked in another bookstore, now gone, with a gentleman of middle years, Southern to the point of parody, very funny and very arch, who nonetheless loved Dickens. My coworker could be unkind, in that lilting Southern way that always seemed to express in equal measure a genuine concern with a withering disdain. He most certainly did not approve of all the stuff he saw me reading then. For philosophy and religion, he had no time at all. For much of anything modern he had no patience. Science he respected, and read, but most of what was new he saw no need of otherwise. I was a puppy then and something in my noisy precocity appealed to him, though he never hesitated to correct what he quite rightly saw as more bark than bite in my conversation. He was, curiously enough, the first champion of a new fangled thing called the internet, and the first truly computer-savy person with whom I'd ever worked. He tried very hard to make me take all that seriously, and to show me something of the possibilities he saw in the new technology. I'm afraid it all went right by me. For fun, one of the activities in which he participated with other like-minded users back then was an ongoing project online that involved tracing and annotating various references and particulars in Dickens. Beyond this admirable business, done in his own time, he also was part of an ongoing game in which the life of certain characters, including Nell Trent, were extended beyond the stories in which they had lived and died. He brought little Nell to America, I remember. As a joke, I would sneak onto his computer when he wasn't in his office, and alter his story in cruel and vulgar ways, meant to outrage him and hopefully make him laugh. I'm afraid I did to poor Nell what many modern critics have assumed the limitations of either Dickens or the Victorians in general had refused to do: I exposed her to every kind of sexual and moral outrage, had her working in all innocence in a New Orleans brothel, for instance, and abandoning her Grandfather temporarily to score dope for a new friend, etc. His fury when he discovered this was hilariously overblown -- though he stuck to the rules of the game and allowed for this, admittedly uninvited collaboration. Rather than delete what I'd added, he would write furiously to correct the misapprehensions I had made of both Nell's character and circumstances. On this went, this battle for the soul of Little Nell, for some weeks, as I remember it. General amusement reigned until he could take it no more. When I finally hinted at syphilis as the possible source of Nell's renewed ill health, he drove me from his desk and forbade me the use of his computer. It was all great fun.

In truth, my older friend's reverence for Dickens, and for the novelist's most famous saintly child, seemed as much an affectation to me as his cigarette holder and his persistent drawl after decades in San Francisco. I had come of age as a reader studying the high Moderns, critics and novelists alike. James was my God. I adopted his disdain for Dickens, and for the Victorian novel in general, as a thing self-evident. Nothing was sacred to me then, except perhaps the perfection of The Golden Bowl, a novel and a novelist not among the favorites of my friend.

If he should ever happen to find this and read it, I offer my sincere apologies for being such an irreverent little monster. He took it all in good humor, but about Dickens he was right, and I was then more ignorant than I would ever have been willing to admit. (I think he understood even then that it was natural in the young to disdain anything revered by their elders, and cut me more slack than I would now should I find myself in similar circumstances. Another instance of the good teachers I've met along the way, and yet another example of why I would make a bad one.)

I won't attempt just here to answer all the criticism of Dickens' most sentimental novel. It is that, supremely so, and only now perhaps can I appreciate it as such, and see that that might indeed be a good. I undertook to read just the famous death of little Nell, after I'd made myself read Hard Times again, just to see if indeed it was as bad as so many had since made it out to be, or as bad as I'd accepted it to be all those years ago. It certainly is everything it was said to be, good and bad, as is the novel in which it is the crowning achievement. The exception I now take to Oscar's witticism is not that it was unfair, but that laughing at such writing as these scenes in The Old Curiosity Shop, while understandable, is itself embarrassing in even a genius of Wilde's rank. It is unseemly to think so little of the sincerity, and very real emotion of so supreme an artist as Dickens. I can assure you, Dickens, whatever he is in this book, is never less than true. Oscar, of anyone, should have been able to appreciate this. If nothing else, the one should have at least shown some respect for other as a writer who had mastered his craft. Oscar, bless him, should have been so lucky. On careful reading, I can say with surprising confidence, there has never been and will probably never be again a writer who could make such a scene with such economy, so little excess or waste, and with such genuine sympathy as Dickens did.

Don't believe me? Try, as I've done, to read that book without indulging in the usual preconceptions about the extravagance of Dickens' emotion. Go on. See for yourself, on reading the whole book up to the point when Nell dies, if any of it feels false or put on or merely conventional. See if the homelessness of an old and confused man, and the innocence and unswerving loyalty of the child who leads him through one hell after another, does not ring just as true. Assume a better acquaintance with the modern pathologies of gambling and the sociology and psychology of poverty, and see if Nell seems over-idealized or false in any particular. The kindness with which the travelers are treated may seem less likely than their suffering, but again, I did not find that forced or false.

For me though, the real test is the famous scene itself, and what comes after it and as a consequence. Without the religion that consoles so many in the book, I can say honestly that I found nothing ridiculous in all the talk of angels and the consolations hereafter. The suggestion that Nell is passive is absurd. Few heroines in literature have been more obviously active, have walked so far, and tried so hard, and trusted so much not just to providence but their own wits to keep body and soul together. The complaint that Nell's is not a truly heroic virtue for never really being tested is grotesque! What more than starvation, exposure and death is required to make this girl's sacrifice seem real, or her death moving? What modern sadism insists that she should end other than she does? That she deserves no friends to observe and try to ease her passing? Is that then what offends the modern sensibility. not her admirable qualities, but the respect they earn in the book?

I tell you frankly, the penultimate chapter, when Nell is gone and all that that means for those she leaves behind is described, is among the best things I have ever read. It is every bit as beautiful as any scene I've ever read.

But here I am doing something of what I specifically did not mean to do. As the bicentennial celebration of Dickens birth approaches, I am determined to do some small service to the great novelist's memory. Reading The Old Curiosity Shop again, on a personal level, and for my own pleasure, I intend a better understanding of his achievement than I had before, and a deeper appreciation of all that he did, and did so supremely well, including the pathos for which later generations would so often seem to have scorned him. All I meant to say here, publicly if to a very small audience, is that I have yet to find a novel by Charles Dickens that is not worthy of another reading. Think of that! Try reading this one, if you still don't believe me. Try reading it without all the accumulated critical reputation and comment, without reference to the quips and dismissals and see for yourselves if there isn't more genuinely good writing in even the most sentimental scenes he ever put to paper, and perhaps the most celebrated and abused novel he ever wrote, than might be imagined by even a seasoned reader of his fiction.

The man amazes me.

I will, I think, be reading the last chapters but one of this book somewhere come the great man's birthday next year. That's what I've already decided. See if I don't. And see, should you be so kind then as to come and hear me do it, if it isn't better than I ever thought it might be. Just you wait and see.

Daily Dose

Thursday, September 1, 2011

Wystan Pays the Bills

William Butler Yeats' came from some real money. His dad was a successful sort of society painter, but their money was older than that, and they had land. And, long before he became the distinguished English gentleman at Faber & Faber, T. S. Eliot could count on his dad and the Hydraulic-Press Brick Company of St, Louis, MO to keep him in bread and spats. Of the three biggest names in English poetry of the last century, it looks to me like only one of 'em, Wystan Hugh Auden, actually had to earn a living. (Among the major Americans in the same period, I count one medical doctor, a number of academics, and not a few bohemians with various day-jobs. It's not, I should think, until James Merrill that we get another leisured gentleman in modern American letters -- unless we count Cole Porter, and why not?) Not that W. H. Auden wasn't perfectly respectable at birth. Dad was a doctor. In the poet's footling youth, it seems safe to say, there wasn't much likelihood he'd have missed many meals, except by choice. Nevertheless, all his adult life Auden paid his way, and the rent, by writing. As someone once said, poetry, like crime, doesn't pay, so for Auden this meant magazine work; travel writing, essays and reviewing. Later in life came lectures, and eventually a comfy chair, but really, if you think about it, only Auden would seem to have been the only "working writer," in the sense of a literary journalist, among the 20th Century masters.

Don't really think of major modern poets having day jobs, but presumably they all did, and do these days. Most would be teachers, I should guess; professors if not of poetry as such, then of literature in general, or more nebulously now, of "writing." In the absence of "a private income" or rich patrons, it may have been so for a very long time, if not always. Homer, if he existed, and Virgil certainly, sang for their respective suppers. It's only when we get to the great Romantics that we begin to assume that Keats, for example, lived on air. Novelists may eventually keep the lights on by means of fiction -- though none of the ones I know personally do -- but poets? Hard to imagine.

It's only now, seeing the "collected prose" before me at the Used Books Desk, I begin to appreciate just how hard and for how long Auden wrote, and wrote, and wrote, and how much of what he wrote was straight-up paycheck-work. Not that that makes any of it less interesting or worthy. Not that I don't now kind of want to own and read the lot.

As it turns out, I have only the first volume of Auden's collect prose in my collection. I've bought and read various individual titles through the years: The Dyer's Hand, Secondary Worlds, etc. The first volume of Mendelson's magisterial edition I know I bought as a publisher's remainder, years back. Still has the mark. It has lived on my shelf, next to the collected verse, for years. Don't remember the last time I opened the book, though the poetry comes down often enough.

(Mendelson also wrote perhaps the best critical biography of Auden, in two volumes -- though both are so dry that a harsh wind might ignite them in the reader's hands.)

Now I think I must have the rest of Auden's prose. I've been exploring these books at lunch ever since they arrived. Full of good things, naturally, and enough of them to make the investment, at least in nice used copies, well worth the price. If for no other reason, reading through a dozen pieces in each has given me a new respect for just how much the poet read, and how widely, and how willing he was to read and review what wouldn't necessarily be books one might have imagined in the library of Wystan Hugh Auden.

Yes, the majority of his reviewing would seem to have been to do with poets and poetry. Doubtless, that was the first thing sent him by editors, but not the only thing he read. There are the Brothers Grimm, for instance, and Twain, and Santayana, and on and on. There's a fair amount on opera. There's also a contemporary review of Camus. There are also car-trips and philosophy and whatnot. One of the things that would seem to have made Auden American, as he spent a good part of his working life proving himself, one way and another, to be, was his willingness to take on just such culture as he found; to delight as much in hot dogs as hohe kultur. (The most fascinating instance of this unexpected openness actually comes from the volume of Libretti and Other Dramatic Writing. Didn't think I'd need to own that, or that I'd probably ever read much in it. A quick glance at the table of contents however produced "Appendix VI: Auden's Lyrics for 'Man of La Mancha.'" Now, how could I not want to know something more about that?! Turns out, Auden was hired and wrote more than a few songs for this show, despite a fundamental disagreement with the playwright about the adaptation -- first thing Auden told him to lose was that nonsense in the last act starting "To dream the impossible dream." And there, a sad end to the business, I should have thought. Still, here's the evidence of some real effort. There's even a story of Auden singing some of this for investors! Now that would have been interesting.)

Reading Auden's prose across his lifetime, rather than as discreet books, introductions or essays, does point up some of the less attractive aspects of his style and his thinking; his fascination with and dated vocabulary from psychoanalysis, the soft-soap-Anglicanism of his later years, and his tendency to gather wool in general. Eliot, who's major poetry I don't know that I will ever feel called on to reread, as an essayist remains perhaps the best critic of his generation. I needn't agree with Eliot to admire his essays. When I find myself disagreeing with Auden, it is generally because I can't make out even what it is he's trying to say. On the writing of poetry, on form and technique, Auden is a fascinating. He is perhaps the best informed, the best read poet of his time and his poetry criticism is invariably worthwhile, whether he's writing as a young man about Pope or as an older man about Marianne Moore. Unlike Eliot however, Auden would seem to have had no particular interest in criticism as a form, and even though both men regularly produced longer prose pieces and serious collections of essays and criticism, I can't quite tell you just what it was Auden intended. Auden's Christianity, for example, or rather his Anglicanism, isn't, not in any recognizable sense. Auden might better be understood as Christian the way Americans of later generations describe themselves as "spiritual." Like them, Auden often uses traditional religious language in ways that would seem to contradict or deny the more usual understanding of even such words as Christian; in Auden's definition a word utterly divorced from both doctrine and faith and entirely to do with the emulation of Christ. I think. Might not have that quite right, and frankly don't really much care, about any of it. There can be no such confusion with Eliot, though again...

It's a mistake to read poets for philosophy, or religion. That's the kind of thinking that would make Pound a better poet than any of 'em, and better certainly than he is to read, Shelley better than Keats because Shelley had politics, and Ginsberg a better poet at seventy than twenty-seven because he'd learned to chant. All very interesting, I'm sure, what Auden thought of Jesus, or Freud, but hardly why I would read Auden, to learn more about either.

What is interesting is reading more of what W. H. Auden -- who somewhere started a lecture on Don Quixote by boldly claiming he'd never finished the novel -- actually wrote about Don Quixote. What Auden wrote about Browning, now that can be interesting. Poets on poets can be quite interesting. And brief is good. With Auden's prose, it seems so far that brief is almost always better. It's his journalism, his straight reviewing then, I seem to find most attractive. I trust his taste. It was Auden after all who first introduced me to Marianne Moore, and Phyllis McGinley, among others. He knows a great poet, major or minor, when he sees one. I like him as a paid reviewer of books. There's just so much of it. I think I'd better buy these books, just to see what all is in them.

Daily Dose

From The Complete Works of W. H. Auden: Libretti and Other Dramatic Writings. 1939 - 1973, edited by Edward Mendelson

From The Complete Works of W. H. Auden: Libretti and Other Dramatic Writings. 1939 - 1973, edited by Edward Mendelson

FOLLY

"Let's get together, folks!

Let's hear a laugh from you,

Swallow a benzedrine,

Put on your Party Smile,

Join the Gang!

To be reserved is gauche, all

Privacy anti-social;

Life's a Bang."

From Auden's Lyrics for "Man of La Mancha"