In the course of our October reading series, Creepy Tales!, we had one rather special evening, made so by the participation of a visitor from that other backwater of bookish souls, the public library. He was wonderful, as I knew he would be. I confess, I'd never actually seen him read before. I knew his reputation, and I've listened to him on the radio many times. I was thrilled when he consented to read for us. We had a Bradbury story from him, perfect for the occasion, read by a man who really knows how to do this sort of thing, and does it all the time. Made me want more.

There is a slight problem though, entirely to do with me, nothing to do with him.

He's a librarian. This means that he does most of his reading aloud at the public library. I hate public libraries.

Now, some of my best friends are librarians. I'm obliged to say that because my personal dislike of the institution is well established, and my experience of public libraries nearly all bad. I always vote "yes" for funding, on principle, and I regularly encourage customers to go to the library when the bookstore in which I work is unable to meet their needs. Hell, I've even urged bright young people to consider pursuing degrees in what is called -- for reasons that can never adequately be explained to me -- "library science." There are so many reasons to support our public libraries that I need hardly review them here. Libraries are great. Public libraries are necessary to a healthy democracy. Librarians, at least the ones I know, are all marvelous individuals; dedicated professionals, champions of literature and literacy, devoted public servants.

The library our guest-reader works and reads in is an architectural jewel, one of the beauty spots in Seattle. Honestly, it is a pleasure just to walk around inside that building. I've insisted that visitors here go check it out. If you're ever in Seattle, or if you live here and have never been, you owe it to yourself to go. You won't be disappointed.

As for me, I can't think of a reason I would ever go there again, unless it was to hear David Wright read aloud. That's the problem.

The Seattle Public Library system is a national model. Their website is a marvelous thing; well made, accessible, cross-referenced to a fair-thee-well. Use it all the time.

Check it out. I've met and liked at least a dozen people that work at the library, and I wasn't just making a joke when I described not a few as being friends. True, my local branch library is an empty shell of a thing and just too sad to think about let alone ever visit again, but the inter-library-loan system in Seattle is excellent, as I understand it, and any number of my coworkers are regular patrons of their closest branches, as well as the central library, and have nothing but praise to sing for the institution. (I know people who work in bookstores all over the city who read most, if not all of their books, by preference, from the library. I know even more people, mostly with small children, but by no means all, who wouldn't have seen a movie in years if it weren't for the DVD selection available from the library.)

If then there is anything bad to say about the Seattle Public Library, I'm hardly the person with any right to say it. I don't go there. Just can't.

For me, as a used bookseller and a bibliophile, there are few things sadder and less appealing than an ex-library book. I own a few myself, discarded years ago from obscure institutions in remote places, books so neglected by readers for so long as to be hardly library books at all; perhaps a discreet, and rather charming old pocket and card -- nearly blank with disinterest -- a stamp or two inside, perhaps a hand-painted code discreetly, even elegantly numbered on the spine. Most former library books are such broken, battered, tatty old things as to make a book-collector cringe, if not weep. Most books with library markings that come across the Used Books buying desk go straight back into the box from which they came. Unsaleable wrecks. Even seeing certain books on a public library shelf can still break my heart. I can still remember, years ago, being in a public library -- a gorgeous place by the way, built with real money and taste, on beautifully maintained and expansive grounds in Southern California -- and coming across not one, but a dozen first British editions of Iris Murdoch, still in their original dustjackets. At the time, I was still busily reading my way through Murdoch for the first time, and as there were at least three of the titles in the library that I'd yet to find used, anywhere, in any edition or printing, at a price I could afford, I determined to borrow at least one from the library to read. It was Murdoch's second novel,

The Flight from the Enchanter, 1956. The book looked like hell: stickers and bar-codes and stamps, inside and out, and no record of anyone having checked it out in a decade or more when I took it from the shelf. Still, I very much wanted to read that novel. Ten pages in -- half a page covered in ink underlining. Even this didn't completely discourage me. The three missing pages further in? That did it.

Barbarians.

That's the kind of thing that drove me from public libraries forever. That, and finding only three hideous copies of the same Austen title on the shelf at one local branch, not my own, mind, already maligned here, and nothing else. Or seeing the collected works of Maeve Binchy, in hardcover in another area library that boasted only two novels by Charles Dickens on the shelf. What else? Well, seeing a private library of exquisite nineteenth and early twentieth century art and music books dumped out with the trash on a loading dock of a public library. I had encouraged the lovely old lady who owned these to donate to them to that same library, just down the road from a bookstore where I was working at the time. While these books were not necessarily valuable books from a commercial standpoint, they were certainly of historical interest, and fabulously, privately bound, and in astonishingly great condition. If nothing else, I'd told the owner, they could go into a library book sale and find new readers to appreciate them. The owner stopped back in at the bookstore on her way home, beaming, to tell me she had handed the books personally to someone at the desk in the library, and they'd seemed quite pleased. (I road a bike to work in those days, so it took me three trips back and forth to rescue the books that weren't already ruined by coffee grounds, etc. These I eventually gave to a coworker, astonished at her good luck.)

I won't even mention all the fine bindings I've seen defaced on public library shelves, the rare books discarded, the inaccessible stacks, the shocking taste, the space wasted on gimcracks and conference rooms and junk...

Obviously, I am not meant for public libraries. I'm fine with that. I'm sure the nation's libraries, should they ever have reason to notice my absence, would be fine with it too. I can't bear to go into the joints anymore? Well, right back at ya, bub, no doubt. Who needs some chubby aesthete swanning through the stacks, moaning, and bitching

sotto voce at the computer terminal because the only copy in the system of Augustine Birrell's second series of

Obiter Dicta is marked "lost"? I don't want to be that public crank. Lord knows, the public library doesn't need another muttering up the place.

It's better so.

I have my own copies of Birrell now.

So now I'm in a fix. I want more of David Wright. In his reading series for the Seattle Public Library, Thrilling Tales, There are so many things I'd love to hear him read; old familiars, and things I know not at all, which is almost more exciting. It isn't just the selections on offer though, but the possibility of hearing this reader read again that tempts and torments me now. This guy is the man. He really is.

David has offered a brilliant

explanation of reading aloud to grown-ups. I'd recommend it to anyone with an interest in giving reading aloud a try, in public, or even just for family and friends. He knows whereof he speaks, people.

More than that though, listening to him is a pure pleasure. I feel an idiot for not having been to hear him at the library before now. If you have the opportunity, you should. Trust me.

As for me and my ridiculous phobias and crochets, pay me no mind. Honestly, ignore all this. I only bring my problem with public libraries up again as an excuse, and because I owe Mr. Wright an apology for never having been to see him in his crib, specially after he was so generous with his time and talent in coming to ours. I hope he can forgive me.

I'll have to just try to be adult about all this nonsense. Just put my head down some fine Fall Monday, and just

go.

I haven't been inside the Seattle Central Library for years now, I'm ashamed to say, and I've never been in the Microsoft Auditorium where David reads. I bet I could just walk right in and never even see a book until David takes one out to read from.

I can do this.

In the course of our October reading series, Creepy Tales!, we had one rather special evening, made so by the participation of a visitor from that other backwater of bookish souls, the public library. He was wonderful, as I knew he would be. I confess, I'd never actually seen him read before. I knew his reputation, and I've listened to him on the radio many times. I was thrilled when he consented to read for us. We had a Bradbury story from him, perfect for the occasion, read by a man who really knows how to do this sort of thing, and does it all the time. Made me want more.

In the course of our October reading series, Creepy Tales!, we had one rather special evening, made so by the participation of a visitor from that other backwater of bookish souls, the public library. He was wonderful, as I knew he would be. I confess, I'd never actually seen him read before. I knew his reputation, and I've listened to him on the radio many times. I was thrilled when he consented to read for us. We had a Bradbury story from him, perfect for the occasion, read by a man who really knows how to do this sort of thing, and does it all the time. Made me want more.

From Letters to Dead Authors, by Andrew Lang

From Letters to Dead Authors, by Andrew Lang An anthology is a dangerous thing, for the insatiable reader. That's what I like to think I am; greedy rather than just self-indulgent or incapable of deeper study. I read so widely as I do then not because I can not concentrate long enough to finish half of what I start, but because I can not wait until I've finished the books I've started before picking up first one other, then another, and another, for fear I suppose of not having time -- or patience -- to read all that I would. Johnson of course offers me many a defense for this, but just here let me say only that I read nowadays mostly according to my "immediate inclination," and I am content to do just that. As for reading every book through, Johnson again:

An anthology is a dangerous thing, for the insatiable reader. That's what I like to think I am; greedy rather than just self-indulgent or incapable of deeper study. I read so widely as I do then not because I can not concentrate long enough to finish half of what I start, but because I can not wait until I've finished the books I've started before picking up first one other, then another, and another, for fear I suppose of not having time -- or patience -- to read all that I would. Johnson of course offers me many a defense for this, but just here let me say only that I read nowadays mostly according to my "immediate inclination," and I am content to do just that. As for reading every book through, Johnson again: Well now, here it is at last. Part of it, anyway, the first part of three. The official hoopla started a couple of months ago, with magazine covers and the like, but for those of us in the book business, this thing has been coming on for a very long time indeed. Looks like it won't be complete anytime soon, either.

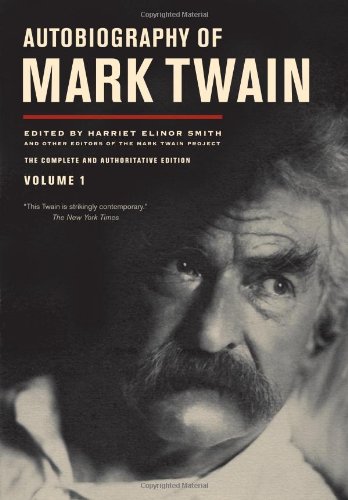

Well now, here it is at last. Part of it, anyway, the first part of three. The official hoopla started a couple of months ago, with magazine covers and the like, but for those of us in the book business, this thing has been coming on for a very long time indeed. Looks like it won't be complete anytime soon, either.

From Stuck Rubber Baby, by Howard Cruse

From Stuck Rubber Baby, by Howard Cruse From Dread and Delight: A Century of Children's Ghost Stories, edited by Philippa Pearce

From Dread and Delight: A Century of Children's Ghost Stories, edited by Philippa Pearce As we wind down the month of Creepy Tales! readings, and begin to prepare for our November reading of Twain, dear P. and I are already thinking ahead. These October readings have been, by any estimation, a great experience. I got to read two Saki favorites that went over pretty well, and a story from the very talented work husband, that I hope was a surprise. (He and his charming boyfriend -- who was in on the secret -- seemed pleased, as did the audience. Good story.) My co-conspiritor and regular reading partner, P., read the hilarious Hell out of her ghost story, to the delight of everyone present. Got to listen to a story read expertly by Seattle Public Library's own David Wright, as our Very Special Guest Star. And our half dozen or more first-time-readers have all been uniformly great, as have been our small but loyal audiences. One more evening of Creep Tales! yet to go, and no reason not to think we will be ending things on a high note. It's been a scream, beginning to end. Safe to say, we want more.

As we wind down the month of Creepy Tales! readings, and begin to prepare for our November reading of Twain, dear P. and I are already thinking ahead. These October readings have been, by any estimation, a great experience. I got to read two Saki favorites that went over pretty well, and a story from the very talented work husband, that I hope was a surprise. (He and his charming boyfriend -- who was in on the secret -- seemed pleased, as did the audience. Good story.) My co-conspiritor and regular reading partner, P., read the hilarious Hell out of her ghost story, to the delight of everyone present. Got to listen to a story read expertly by Seattle Public Library's own David Wright, as our Very Special Guest Star. And our half dozen or more first-time-readers have all been uniformly great, as have been our small but loyal audiences. One more evening of Creep Tales! yet to go, and no reason not to think we will be ending things on a high note. It's been a scream, beginning to end. Safe to say, we want more. From Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works

From Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works

From Indolent Essays, by Richard Dowling

From Indolent Essays, by Richard Dowling Holidays provide a marvelous excuse for this sort of thing. Mark your calendars. Even something as fundamentally silly as Halloween can be put to use in just this way; a comfortable chair, a strong light in an otherwise dark room, and a book of poetry or two, and I can justify reading right out loud poem after poem, about death, for instance. Now, I know that death isn't quite the word usually paired with holiday, but come October and the furnace kicks on and the nights get long, what could be more appropriate than a deathless line -- or twenty -- on the one end to which everything comes? What could be more deliciously indulgent, less adult, better fun?

Holidays provide a marvelous excuse for this sort of thing. Mark your calendars. Even something as fundamentally silly as Halloween can be put to use in just this way; a comfortable chair, a strong light in an otherwise dark room, and a book of poetry or two, and I can justify reading right out loud poem after poem, about death, for instance. Now, I know that death isn't quite the word usually paired with holiday, but come October and the furnace kicks on and the nights get long, what could be more appropriate than a deathless line -- or twenty -- on the one end to which everything comes? What could be more deliciously indulgent, less adult, better fun?