THOMAS WYATT

THOMAS WYATTThomas Wyatt,

Craving quiet,

Bade love farewell

From a prison cell.

"I hold any writer sufficiently justified who is himself in love with his theme." -- Henry James

From Poems, by Amelia Opie

From Poems, by Amelia Opie Thanks for this photo to Matthew, and to everyone in the crowd tonight, specially those good souls who stood at the back, for coming out for 84, Charing Cross Road!

Thanks for this photo to Matthew, and to everyone in the crowd tonight, specially those good souls who stood at the back, for coming out for 84, Charing Cross Road!

From Imaginary Conversations, by Walter Savage Landor

From Imaginary Conversations, by Walter Savage Landor Luckily, as neither of us is the young actor we once fancied we might be, we needn't memorize but only read these letters aloud -- thus our reading copies always on the table before us.

Luckily, as neither of us is the young actor we once fancied we might be, we needn't memorize but only read these letters aloud -- thus our reading copies always on the table before us. Here we are trying to put back something we took out. Ah, the joys of editing changes and collating unnumbered pages.

Here we are trying to put back something we took out. Ah, the joys of editing changes and collating unnumbered pages. Dear P. in full flight, reading Helene Hanff's marvelous letters.

Dear P. in full flight, reading Helene Hanff's marvelous letters. This, in rehearsal, is the kind of improvisation too little talked about. Don't have a paperweight? One more reason to wear clogs.

This, in rehearsal, is the kind of improvisation too little talked about. Don't have a paperweight? One more reason to wear clogs.  Finally, The Old Boy mutters movingly into the imaginary microphone -- without once looking up from the page -- and worries still about the time.

Finally, The Old Boy mutters movingly into the imaginary microphone -- without once looking up from the page -- and worries still about the time. From Songs & Sonnets, by John Donne

From Songs & Sonnets, by John Donne I once overheard an old friend, not without affection, describe my character to a third party as being comprised of "equal parts indignation and enthusiasm." I've always treasured that characterization, and thought it just, so far as it goes, which has often as not proved to be further than it should. When I was younger, like all young men, I was quick to both, and again like young people generally, I tended to overstate. Nothing I resented could I find other than outrageous, nothing I disliked but I hated it, and nothing and no one I liked but I loved. Books, friends, lovers and enemies all had from me something of the same intensity, received something like the same consideration, and suffered the effect of what another friend of that period described as my "dive and rip" method of getting acquainted. I could not at that period get to know someone but that I wanted and felt I needed to know everything about them: what they thought, what they read, who and what they loved and why. Even with a good new book, I could not read it but then had to read everything about the subject, everything I could find by and about the author, everything and anything that might sustain my interest and extend it to the next book and the next. In just this way I exhausted not just my friends, and a few teachers, but the pawky selection to be had in the little libraries to which I had access at the time. On subjects as diverse as OZ, the American Civil War, Edgar Allen Poe, the mafia, fascism, Daumier's caricatures, Emma Goldman and UFOs, I remember reading my way in turn through every book, encyclopedia entry and article there was to be had in my home town. When I came to serious literature, I attacked fiction in just this same way, convinced that if I meant to appreciate anything, I had to read everything and know whatever there was to know about everything I read. I still think that not a bad way for a young man to read. If history fueled my sense of injustice, and biography gave me heroes, if reading The King James Bible taught me less religion and more about verse than I realized at the time, if reading Twain, curiously enough, made me better prepared when I came to read James to appreciate his humor, it all proved to be a better preparation than much of the little formal education I received for everything that's come after. To a surprising extent, I still read, and live by the light that was kindled in me then by the books I happened on more often than I was handed. I can't quite imagine, looking back, why or how I read what I did, other than to marvel that the day must have had more hours in it when I was a boy than it does now, and I can't help but regret that there were not more adults along the way who might have better directed my interests and guided my reading, to say nothing of my affections and my time, into more productive paths, but nothing I now think did I really waste, and for such help as I had I am grateful.

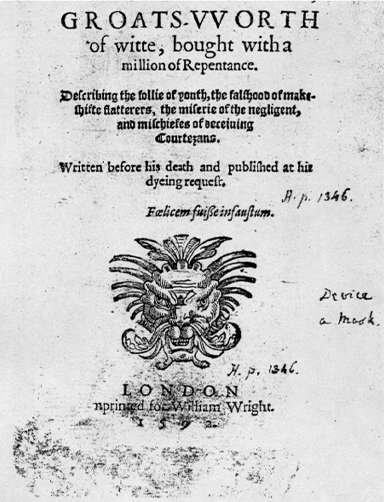

I once overheard an old friend, not without affection, describe my character to a third party as being comprised of "equal parts indignation and enthusiasm." I've always treasured that characterization, and thought it just, so far as it goes, which has often as not proved to be further than it should. When I was younger, like all young men, I was quick to both, and again like young people generally, I tended to overstate. Nothing I resented could I find other than outrageous, nothing I disliked but I hated it, and nothing and no one I liked but I loved. Books, friends, lovers and enemies all had from me something of the same intensity, received something like the same consideration, and suffered the effect of what another friend of that period described as my "dive and rip" method of getting acquainted. I could not at that period get to know someone but that I wanted and felt I needed to know everything about them: what they thought, what they read, who and what they loved and why. Even with a good new book, I could not read it but then had to read everything about the subject, everything I could find by and about the author, everything and anything that might sustain my interest and extend it to the next book and the next. In just this way I exhausted not just my friends, and a few teachers, but the pawky selection to be had in the little libraries to which I had access at the time. On subjects as diverse as OZ, the American Civil War, Edgar Allen Poe, the mafia, fascism, Daumier's caricatures, Emma Goldman and UFOs, I remember reading my way in turn through every book, encyclopedia entry and article there was to be had in my home town. When I came to serious literature, I attacked fiction in just this same way, convinced that if I meant to appreciate anything, I had to read everything and know whatever there was to know about everything I read. I still think that not a bad way for a young man to read. If history fueled my sense of injustice, and biography gave me heroes, if reading The King James Bible taught me less religion and more about verse than I realized at the time, if reading Twain, curiously enough, made me better prepared when I came to read James to appreciate his humor, it all proved to be a better preparation than much of the little formal education I received for everything that's come after. To a surprising extent, I still read, and live by the light that was kindled in me then by the books I happened on more often than I was handed. I can't quite imagine, looking back, why or how I read what I did, other than to marvel that the day must have had more hours in it when I was a boy than it does now, and I can't help but regret that there were not more adults along the way who might have better directed my interests and guided my reading, to say nothing of my affections and my time, into more productive paths, but nothing I now think did I really waste, and for such help as I had I am grateful. From Greene's Groat's-Worth of Wit, bought with a million of Repentance, by Robert Greene

From Greene's Groat's-Worth of Wit, bought with a million of Repentance, by Robert Greene Dear P., my fellow reader for Wednesday's event in celebration of the 40th Anniversary of 84, Charing Cross Road, asked me yesterday if I was "nervous, yet." Truth be told, I'm not. In the first place, as she will be doing all the heavy lifting by reading the much longer letters from Helene Hanff to her friend FPD, while I will only be reading the more usually business-like replies from that bookseller, I frankly have less about which to worry. Secondly, I have complete confidence in the material, specially as it will be read by dear P., to amuse and entertain our presumably already sympathetic audience. This reading is of the kind to which one might confidently invite anyone, but count on only those who know the book to show up. There's nothing unhappy in that. When we read Dorothy Parker together, with others from the bookstore, there were in that audience no doubt at least a few people who knew of Dorothy Parker only a stray quote, or who knew her only by her reputation as a wit, if at all. To show that there was more to her than that was one of the pleasures of the evening for all involved. Reading Blake, or Dickens, on the occasions of their birthdays, to the small but enthusiastic audiences that attended either evening, was an opportunity for me, however inadequately, to let people hear the words of two very different kinds of genius read aloud again, possibly in either case, for the first time. Reading selections from Helene Hanff's 84, Charing Cross Road will, I think, be more like a reunion. If one knows the book at all, even if only from the movie made of it, one either already loves the author, her eccentric reading-lists, the story of her friendship with the booksellers at Marks & Co., and the world, now largely past, memorialized therein, or one could not be made to care about such things to begin with.

Dear P., my fellow reader for Wednesday's event in celebration of the 40th Anniversary of 84, Charing Cross Road, asked me yesterday if I was "nervous, yet." Truth be told, I'm not. In the first place, as she will be doing all the heavy lifting by reading the much longer letters from Helene Hanff to her friend FPD, while I will only be reading the more usually business-like replies from that bookseller, I frankly have less about which to worry. Secondly, I have complete confidence in the material, specially as it will be read by dear P., to amuse and entertain our presumably already sympathetic audience. This reading is of the kind to which one might confidently invite anyone, but count on only those who know the book to show up. There's nothing unhappy in that. When we read Dorothy Parker together, with others from the bookstore, there were in that audience no doubt at least a few people who knew of Dorothy Parker only a stray quote, or who knew her only by her reputation as a wit, if at all. To show that there was more to her than that was one of the pleasures of the evening for all involved. Reading Blake, or Dickens, on the occasions of their birthdays, to the small but enthusiastic audiences that attended either evening, was an opportunity for me, however inadequately, to let people hear the words of two very different kinds of genius read aloud again, possibly in either case, for the first time. Reading selections from Helene Hanff's 84, Charing Cross Road will, I think, be more like a reunion. If one knows the book at all, even if only from the movie made of it, one either already loves the author, her eccentric reading-lists, the story of her friendship with the booksellers at Marks & Co., and the world, now largely past, memorialized therein, or one could not be made to care about such things to begin with. From Essays and Marginalia, and Poems, by Hartley Coleridge

From Essays and Marginalia, and Poems, by Hartley Coleridge

From Herbert: Poems, by George Herbert

From Herbert: Poems, by George Herbert From Such Nonsense! An Anthology, by Carolyn Wells

From Such Nonsense! An Anthology, by Carolyn Wells

_Austin_Dobson_by_Frank_Brooks.jpg/170px-(Henry)_Austin_Dobson_by_Frank_Brooks.jpg) From Later Essays: 1917 - 1920, by Austin Dobson

From Later Essays: 1917 - 1920, by Austin Dobson Here then are the fruits of our reprinting project, some of the books from 84, Charing Cross Road reprinted using the bookstore's new Espresso Book Machine! The 40th Anniversary of the book's publication inspired us to host a reading at the bookstore on the 28th, at 7PM. In addition to having Hanff's own book, and the in-print books mentioned, for the night of the reading, we decided to reprint as many of the out-of-print titles Helene Hanff ordered from Marks & Co. as possible.

Here then are the fruits of our reprinting project, some of the books from 84, Charing Cross Road reprinted using the bookstore's new Espresso Book Machine! The 40th Anniversary of the book's publication inspired us to host a reading at the bookstore on the 28th, at 7PM. In addition to having Hanff's own book, and the in-print books mentioned, for the night of the reading, we decided to reprint as many of the out-of-print titles Helene Hanff ordered from Marks & Co. as possible.

From A Book of Sonnets, edited by Robert Nye

From A Book of Sonnets, edited by Robert Nye From Collected Poems, by Alexander Pope

From Collected Poems, by Alexander Pope