This weekend, I've finally been doing my duty -- a bit of it anyway -- and have now read at least thirty pages out of more than a dozen books sent to me for consideration by the committee on which I so happily serve. I was pleased to have found, in at least two or three, something well worth reading more of. My reluctance then, to again take up this task, has had less to do with reading books I would never choose to, had it not rather unexpectedly become my responsibility to do so, than with reading good books when I might be reading a great one. Now that, is about as snooty as I choose to ever admit to being, here. I've tried very hard not to use this space as an abattoir. I can say what I please here, but having this opportunity hasn't altered my position relative to literature or bookselling; I love the former, but earn my living from latter. I am not myself a professional writer. l am not now nor have I ever made any claim to being a novelist or a journalist or anything else much connected to either the creation or promotion of literature. I wrote a novel once. It was bad. I don't regret the attempt, I even enjoyed the doing of it, but neither do I much mourn my failure. I have not been made bitter by what I do not do, as I've found greater satisfaction than I might otherwise have imagined in doing the little I do for literature by working in a great bookstore. And as a bookseller, I wouldn't want to actively discourage anyone from reading even the worst books, so long as the reader buys them first, and from me. When I have allowed myself, just here, a discouraging word or two or two hundred about a particular book or contemporary author, I have tried consistently immediately thereafter to recommend something better. That, it seems to me, is very much in keeping with the way in which I earn a living. I am not a critic. I am not paid to make evaluations of the relative merits of this, as opposed to that, book, in any context other than customer satisfaction. That I do happily. It is my job. And even when I am not on the job, I do try to be a little circumspect. There are, for example, any number of perfectly respectable contemporary writers, some of them even rather beloved by the reading public, I would never again willingly read, writers whose success frankly baffles me, or whose reputations I might personally find grossly inflated. Well, who cares? I might happily trash such people with my friends, but I don't think, my credentials as reader being no better than they are, that I really need to nominate myself as the St. George to take on such dragons, or this little blog, as the best means to defeat them. Do you? No. There are critics, literary, journalistic, academic, and popular, and more than enough of those, whose job, it would seem to me, is to do exactly that. Instead, in my cranky, rather inconspicuous way, I feel free to swell the occasional chorus of decent, or add my small voice to a more general ballyhoo, but otherwise, I prefer to express only my own, entirely eccentric opinion here, for whatever it may be worth in the way of endorsement, amusement or warning to only the warm but narrow circle of my friends and few readers. And so I feel safe in allowing myself this confession, as it can harm no one much but me, and that only in reinforcing my reputation as a blatant fogey, and state flatly, whatever the quality of the books sitting in my stack for review by the committee, I would rather be reading Stendhal.

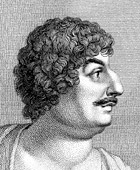

This weekend, I've finally been doing my duty -- a bit of it anyway -- and have now read at least thirty pages out of more than a dozen books sent to me for consideration by the committee on which I so happily serve. I was pleased to have found, in at least two or three, something well worth reading more of. My reluctance then, to again take up this task, has had less to do with reading books I would never choose to, had it not rather unexpectedly become my responsibility to do so, than with reading good books when I might be reading a great one. Now that, is about as snooty as I choose to ever admit to being, here. I've tried very hard not to use this space as an abattoir. I can say what I please here, but having this opportunity hasn't altered my position relative to literature or bookselling; I love the former, but earn my living from latter. I am not myself a professional writer. l am not now nor have I ever made any claim to being a novelist or a journalist or anything else much connected to either the creation or promotion of literature. I wrote a novel once. It was bad. I don't regret the attempt, I even enjoyed the doing of it, but neither do I much mourn my failure. I have not been made bitter by what I do not do, as I've found greater satisfaction than I might otherwise have imagined in doing the little I do for literature by working in a great bookstore. And as a bookseller, I wouldn't want to actively discourage anyone from reading even the worst books, so long as the reader buys them first, and from me. When I have allowed myself, just here, a discouraging word or two or two hundred about a particular book or contemporary author, I have tried consistently immediately thereafter to recommend something better. That, it seems to me, is very much in keeping with the way in which I earn a living. I am not a critic. I am not paid to make evaluations of the relative merits of this, as opposed to that, book, in any context other than customer satisfaction. That I do happily. It is my job. And even when I am not on the job, I do try to be a little circumspect. There are, for example, any number of perfectly respectable contemporary writers, some of them even rather beloved by the reading public, I would never again willingly read, writers whose success frankly baffles me, or whose reputations I might personally find grossly inflated. Well, who cares? I might happily trash such people with my friends, but I don't think, my credentials as reader being no better than they are, that I really need to nominate myself as the St. George to take on such dragons, or this little blog, as the best means to defeat them. Do you? No. There are critics, literary, journalistic, academic, and popular, and more than enough of those, whose job, it would seem to me, is to do exactly that. Instead, in my cranky, rather inconspicuous way, I feel free to swell the occasional chorus of decent, or add my small voice to a more general ballyhoo, but otherwise, I prefer to express only my own, entirely eccentric opinion here, for whatever it may be worth in the way of endorsement, amusement or warning to only the warm but narrow circle of my friends and few readers. And so I feel safe in allowing myself this confession, as it can harm no one much but me, and that only in reinforcing my reputation as a blatant fogey, and state flatly, whatever the quality of the books sitting in my stack for review by the committee, I would rather be reading Stendhal.I made the mistake this morning, in the midst of my assigned reading, of picking up The Red and the Black, without really meaning to, and taking it with me on an errand of nature. Having read no more than the first, short chapter, I was reminded of just how great this novel is; how rich in character and politics, in atmosphere and history, and of just how funny Stendhal can be. He's ruined me, at least for today. The thought of turning now off the wide provincial avenue leading me again through Verrieres, to the old Abbe Chelan and on to Abbe Pirard, and to Julien Sorel and the rest, seems impossible. What, after all, is my assigned direction for the day, what are the charms of my original slog, with such a happy alternative already in my hand? With whom ought I to spend the evening? The unaffected, if rather meandering poet, in her surprisingly lengthy memoir, shedding metaphors like so many sunbeams on the hard, white, winter beauties of Alaska? That has always been a place I hope never to go, even before they loosed their favorite daughter on the national scene. Or should I read another fishing story? Should I have another go at one of the boating books? Or should I reconsider my initial judgement, perhaps too hasty, all but certainly too harsh, of the book about the remembered excitement of local football, as it used to be played, back in the glory days? Setting aside all the nonfictional celebrations of rugged outdoorsiness and endangered slugs and the like, perhaps I ought skip past all the heartwarming stories of heroic pets, and go straight to the independently published fiction by local authors. This is, after all, just the sort of thing amidst which I had hoped to discover something so original and quirkily, if brilliantly written as to justify, in my mind if nowhere else, the whole purpose of our review committee. Last year, I found one or two very good books, short story collections rather than novels, admittedly, that I thought well worth championing, if to little or no effect on my committee, then at least, in a modest way, in the bookstore. But of the fiction I've started from my stack of nominated books, from small and large presses alike, I have, to date, this year not found a single one that was not already better written, by the late John Gardner for instance, or experienced already as a television movie on Lifetime, ("television for women!") or read a hundred other times, and more happily, in short stories, twenty years ago, in a collection from Pushcart.

No. I'm afraid, having allowed myself even so much as a taste of a real masterpiece, the idea of going back to common grub, however nutritious or lovingly made from scratch and scraps, makes me more than a little queasy just now. It is like discovering champagne in a juice bar! It's like finding foie gras on a table of Denny's. Who has the stomach for a half eaten Grand Slam, after even a nibble of real French cuisine?

So there it is and here I am. Why anyone should think of putting such a horrible little snob onto anything as democratic as a working committee, I can't quite imagine. As I've said, I can't even justify my position by insisting I was meant for better things. I'm not. Nothing good can come of my reading Stendhal again, instead of reading the books I agreed to read. Nothing good. I can't even dare to suggest that in reading The Red and the Black, again, that I'll have anything intelligent or original to say about it afterwards, if only here. I don't know that I will. It's more than a little embarrassing.

And now, if you will forgive me, if you can, I'm going to go eat leftover biscuits and gravy and read Chapter Seven, "Elective Affinities."